Tre Donne: Kitty Genovese, Diane di Prima, Virginia Apuzzo and the Roots of Italian-American Feminism in 1960s New York

By Marcia M. Gallo

Kitty Genovese, Diane di Prima, and Virginia Apuzzo are iconic Italian American New Yorkers who came of age in the 1950s and challenged familial and social expectations. All three present novel perspectives on women’s oppression and liberation in the 1960s and beyond. Yet rarely are they considered together as examples of ethnic “gender rebels.”

Kitty Genovese was a smart, passionate lesbian who became a national symbol of urban apathy after her 1964 murder in Queens at age 28. Diane di Prima helped launch the Beat literary movement in New York and has been a prolific feminist poet, playwright, memoirist, and activist throughout her life. Virginia Apuzzo is a former nun and pioneer gay rights, feminist, and AIDS organizer and leader who was appointed to high-level positions in the administrations of former New York Governor Mario Cuomo and President Bill Clinton. All three of them are part of my current research that reexamines mid-twentieth century feminism by centering women of color, ethnic women, working class and poor women — artists, public intellectuals, activists — who have been subsumed or ignored in traditional accounts of American women’s liberation movements.

Kitty Genovese, early 1960s.

Kitty Genovese in Queens, 1961. Popularized courtesy of the New York Times.

“No one helped…”

Kitty Genovese was described by everyone who knew her as “large and in charge” despite her small stature. After graduation from Prospect Park High School in 1953, she acceded to social expectations by securing clerical work and marrying, but both the job and the marriage soon ended. When her close-knit family moved from Brooklyn to New Canaan, Connecticut in 1954, Kitty, a true urbanite, did not join them; instead, she chose to live and work in Queens. She managed a working-class bar, Ev’s Eleventh Hour, in the then predominantly white neighborhood of Hollis. From all accounts, Kitty “ran the place.” She insured that the jukebox was stacked with jazz and other popular music, loved to talk politics — she was a big LBJ supporter — and had a huge heart and open wallet. She also showed off her flamboyant spirit by driving a red Fiat around New York City.[1]

But what catapulted Kitty Genovese into infamy was not her life but her death. Two vicious early morning assaults in Kew Gardens on a bitter-cold Friday March 13, 1964 robbed her of her future and cemented her in place as a victim. Two weeks after her death, the recently named Metropolitan Editor of the New York Times A. M. Rosenthal published the infamous front-page story headlined “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police.” But it was the subhead that established the central concern: “Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector.”[2]

The story went viral, but much of it was not true. One of Genovese’s neighbors reported he had interrupted Winston Moseley’s first attack by shouting at him; Moseley ran away but then returned. Another neighbor reported that he did call the police but none arrived. A third neighbor was awakened, called police, and held Genovese in her arms as they waited for the ambulance to arrive. Kitty died on the way to the hospital. But the neighbors’ accounts were dismissed as all of New York — and, soon, the nation — was tsk-tsking about the callous people in Kew Gardens who witnessed a gruesome murder yet did nothing to help the victim. Fears of apathy seized the city, so much so that a crucial aspect of the story often was ignored: Moseley was captured six days later because neighbors in nearby Corona saw him attempting to burglarize a home, confronted him, disabled his car, and directed police to his whereabouts. In the frenzy of shaming, there was little media attention paid to anything that might disrupt the apathy narrative.

Rosenthal also chose to eliminate personal information about Genovese from the Times’ coverage, including her lover, Mary Ann Zielonko, who was asleep at their home when Genovese was killed. Until Zielonko gave an interview in 2004 and described in detail her anguish at losing the woman she loved on the day of their one-year anniversary, she was silenced and Genovese was reduced to a cipher. Instead, Rosenthal promoted false accounts of the Genovese crime in order to preach the importance of what he called “personal responsibility” for solving social problems and to diminish those who were engaged in collective activism, especially for civil rights.[3]

The real story is that New York in 1964 was a significant site of organizing and activism against police brutality and for racial integration. At the same time that Rosenthal was warning about the “sickness” of apathy as represented by the Genovese crime, the Times featured stories about the increasing protests, vigils, walkouts, and demands by activists to end segregation in New York City. Like many white liberals in 1964, Rosenthal was growing impatient with such large-scale anti-racist activism.

Rosenthal also rationalized the failure of police in Queens to solve the series of assaults against women that Moseley had committed for months before he killed Genovese. Although legal documents detailed Moseley’s sexual attacks on Genovese as she lay dying, the Times’ coverage ignored them too. It was not until 1975 that New York writer and feminist Susan Brownmiller revealed that rape was a significant part of the Genovese crime. It still is rarely mentioned that Moseley’s other violent sexual assaults included the rape and murder of Anna Mae Johnson, a young black woman who also lived in Queens, just two weeks before he killed Genovese.

Despite the distortions and omissions, for many people — especially women — the story of Kitty Genovese’s death was a powerful cautionary tale. As researchers have dug deeper, the story has been challenged. And the publicly shared memories of people who were closest to her, such as Mary Ann Zielonko, her best friend Angelo Lanzone, and her brother William Genovese, brought her to life. For example, Mary Ann told me that one of the things that she and Kitty loved to do was go to Greenwich Village to hear folk music and poetry. I wonder if perhaps they were in the audience at one of Diane di Prima’s readings there in 1963 or 1964.[4]

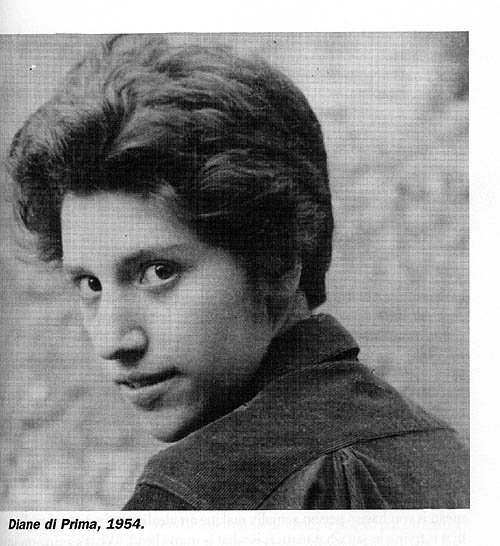

Diane di Prima in 1954 New York, four years before her first book of poetry was published.

This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards

One of the few celebrated female poets of the Beat era was an Italian American woman, Diane di Prima, who for more than fifty years has insisted that we reconsider the body, female sexuality, and normative gender roles.[5]

From a very early age, di Prima knew she wanted to be a writer. Like Kitty Genovese, she also knew she wanted to live a life different than the one she saw around her. In an interview with poet David Meltzer several years ago, she placed her need to rebel in reaction to the conservatism of the Italian American family she grew up in. However, in a 2002 interview, she also remembered, “where I was lucky in my own life was that I had a grandfather who was an anarchist… He would read Dante to me and take me to the old peoples’ anarchist rallies, and all this showed me these other possibilities.”

As di Prima said years later, “the imprint that I got from him, and from my grandmother as well, was of two people who weren’t afraid, at least from my child’s point of perspective…I was born in 1934, during the depression, and everyone seemed to be frozen with terror. We… will… do… what… we… are… told! And I don’t think it’s changed that much.”[6]

Instead, di Prima at age 14 fully committed to becoming a writer and viewed it as a serious vocation. She has kept her promise. She published her first book of poetry, This Kind of Bird Flies Backwards, in 1958 and today she is the author of 43 books of poetry and prose. Her work has been translated into at least twenty languages and she has received numerous grants, awards, and honors, including being named the Poet Laureate of San Francisco, her home for thirty-five years, in 2009.

Embodying the Beat perspective of sharing and promoting not only her own work but that of her colleagues, she, along with with fellow Beat and lover LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) helped start the New York Poets Theatre and the Poets Press, which published poetry and other works which no one else at the time would touch. In addition to being a writer, di Prima also was determined to be a mother, married or not, and has five children. Her insistence on challenging traditional relationships, while also celebrating reproduction, passion, and women’s power, are a hallmark.

In her major work Loba, first published in 1978 as a work in progress, to which she has added new poems in a revised 1998 edition, di Prima expands her horizons of the possible for femaleness, denoting the mystical, protective, and motherly tendencies of the female character, a “warrior woman.” In 2011 di Prima teamed up with filmmaker Melanie La Rosa to create the impressionistic documentary, The Poetry Deal: A Film with Diane di Prima. Now well into her 70s, facing serious health challenges yet still writing, still funny, fierce, and philosophical, it shows di Prima as a pioneer who broke boundaries of class and gender in her writing and publishing. The film looks back on more than 50 years of poetry, activism, and cultural change from the perspective of a woman who was intimately involved in the Beat movement and has never stopped challenging herself, and us, to think more creatively, broadly, and lovingly.[7]

Diane di Prima’s willingness to run afoul of convention and her fidelity to truth telling has not been easy. Although her body of work is extensive and impressive, as scholar Roseanne Giannini Quinn asked in 2003, “why has so little critical attention been paid to her?” Quinn argues that di Prima’s work represents a distinctly Italian American feminist theoretical consciousness and that di Prima defies Italian cultural norms for merely writing about sex, not to mention claiming experiences with multiple partners, male and female. Quinn asserts that di Prima’s biggest transgression is that she “dares to write about herself in the first place.”[8]

Virginia Apuzzo makes history in 1997 with her appointment to a high-level White House position by President Bill Clinton. Clipping from The Advocate.

“Lesbian Ex-Nun Wins Top State Job”

The bold leadership of a third Italian American New Yorker, Virginia Apuzzo, also shone brightly at a time when very few such leaders existed. She joins the ranks of other political donne such as Eleanor Smeal, Janet Napolitano, Geraldine Ferraro, Nancy Pelosi…but Ginny Apuzzo made her mark as an out and proud lesbian.

Apuzzo was raised in a working-class family in the Bronx. She graduated from Cathedral High School in 1959 and received a BA in History from SUNY New Paltz and an MA from Fordham. At age 26, Apuzzo entered the Sisters of Charity order despite having known for more than half of her life that she was sexually attracted to women. She credits the era of Vatican II, a time of more openness and experimentation within Catholicism. While she was in the convent, Apuzzo immersed herself in studies of theology and redemptive politics. She describes this period in the church as activist. “I was totally persuaded that that is a sanctified pursuit. That protest is necessary for change. That resistance is a good and decent thing. And so I did.” She left the convent after three years, in 1969, when she felt she had resolved the issue of her sexuality, and came out as lesbian.[9]

One of the things that Diane di Prima and Virginia Apuzzo have in common is their involvement in interracial relationships as well as civil rights activism. For ten years, Apuzzo shared a home, a life, and political work with African American activist Betty (Achebe) Powell. When they met, it was Powell who was the out lesbian. Together they helped create and shape some of the key organizations of the early gay and lesbian movement.

Apuzzo also became active in electoral politics within a decade of leaving the convent. She remembers that she “lobbied the Democratic platform committee for what was supposed to be NOW’s four demands: right to choose, daycare, Equal Rights Amendment, and lesbian and gay rights. I saw firsthand the duplicity around the commitment to lesbian and gay rights. I listened when some of the monuments in the feminist movement said ‘we got three of four, that’s not bad.’ Well, I was the fourth, and that ain’t good.”[10]

Soon her voluntary activism with groups like the Gay Rights National Lobby led to positions of national prominence. In 1980 Apuzzo became a delegate to the Democratic National Convention and co-authored the first gay and lesbian civil rights portion of the party’s platform. She took on leadership of the National Gay Task Force in 1983 and then was named by New York Governor Mario Cuomo to a number of important positions, including director of the New York State Consumer Protection Board and the Department of Civil Service.

In her oral history interview with historian Kelly Anderson, archived at Smith College, she tells the story of then-Governor Mario Cuomo calling her into his office at the end of her first week. “I walked in, and he said, ‘You got more press than I did this week, Apuzzo.’ I said, ‘I’m really sorry about that, Governor.’ I mean, you know, I didn’t talk to anybody, so, yeah, I was like a little cowering there. So I said, ‘That headline. So embarrassing.’ He picked it up (the newspaper with a headline and photo of her). He had it on his desk and he said, ‘Why? This is a good headline.’ Now, picture Mario Cuomo. ‘This is a good headline,’ he said. I said, ‘Why?’ He said, “Lesbian Ex-Nun Wins Top State Job.’ A bad headline would be ‘Lesbian Ex-Nun Steals Top State Job,’ he said. ‘And worse would be, ‘Lesbian Ex-Nun Hustles Top State Job.” So that became the tenor of our relationship, and I loved him dearly…he took a chance on me, bringing me to government, putting me into a position that had nothing to do with gay issues and the circumstances made it something to do with gay issues — AIDS — and he made it possible for me to end up at the White House.” In 1996, President Bill Clinton named Apuzzo Associate Deputy Secretary of Labor at the United States Department of Labor. A year later, Clinton appointed her Assistant to the President for Management and Administration, making her the top-ranked openly gay person in the Clinton Administration.[11]

Thirty years ago, Apuzzo gave a powerful keynote speech to the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. In it, she challenged the LGBTQ movement with these words: “Consider the fact that one of the many things we share with the feminist movement is, not surprisingly, the same enemies for the same reasons. They strive to establish the norm and everything beyond that norm is fringe. The fewer the options available to members of the women’s movement or the gay and lesbian movement, the greater the homogeneity in society. The greater the degree of sameness that exists, the greater the penalty for those who refuse to be homogenized.”[12]

Virginia Apuzzo, Diane di Prima, and Kitty Genovese refused to be homogenized. Their singular and combined contributions to politics, culture, and social justice can provide new ways of thinking about feminism of past decades while providing inspiration for feminists now and in the future.

This essay is based on a November 28, 2018 talk given at Baruch College. I am grateful to Dr. Vincent DiGirolamo, Professor of History, for his invitation to speak in honor of Italian American Heritage Month 2018. I also want to thank the Baruch College History Club, the John D. Calandra Italian American Institute of Queens College, and the Italian Heritage and Culture Committee of New York.

Marcia M. Gallo is Associate Professor of History at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She is the author of "No One Helped" Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy.

Notes

[1] Marcia M. Gallo, “No One Helped”: Kitty Genovese, New York City, and the Myth of Urban Apathy (Cornell University Press, 2015), xiv-xvi.

[2] Martin Gansberg, “37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police,” New York Times, March 27, 1964, 1.

[3] A. M. Rosenthal, “Study of the Sickness Called Apathy,” New York Times Magazine, May 30, 1964, SM24. See also A. M. Rosenthal, Thirty-Eight Witnesses (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1964).

[4] Mary Ann Zielonko, telephone interview, July 16, 2009.

[5] The Graduate Center of the City University of New York’s Center for the Humanities offers scholarships for graduate student research, including a specific opportunity to explore further Diane di Prima’s life and work. For more information, see

https://historyprogram.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2018-lost-found-grants-archival-research-grant-diane-di-prima-fellowship-legacy-fieldwork-grant/

[6] Dale Smith, “Giving Everything: On Diane di Prima,” Los Angeles Review of Books, January 26, 2013; Joseph Matheny, “An Interview with Diane DiPrima [sic],” Literary Kicks, November 15, 2002; www.litkicks.com/Archives

[7] Melanie La Rosa, The Poetry Deal: A Film with Diane di Prima, 2014.

http://www.melanielarosa.com/thepoetrydeal/

[8] Roseanne Giannini Quinn, “‘The Willingness to Speak’: Diane di Prima and Italian American Feminist Body Politics,” MELUS, Vol. 28, No. 3, Italian American Literature (Autumn 2003).

[9] Virginia Apuzzo, interview by Kelly Anderson, transcript of video recording, June 2, 2004, Voices of Feminism Oral History Project, Sophia Smith Collection.

[10] Ibid. p. 29.

[11] Ibid. pp. 52-53.

[12] Virginia Apuzzo, “Creating Change, November 20, 1988” in Josh Gottheimer, Bill Clinton, and Mary Frances Berry, eds. Ripples of Hope: Great American Civil Rights Speeches (Jackson TN: Perseus Books, 2003). See also Virginia M. Apuzzo, “A Call to Action,” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 13:4 (2001), 1-11.