Walking Harlem: An Interview with Karen Taborn

Today on the blog, Kate Papacosma talks to Karen Taborn about the process of developing her book, Walking Harlem: The Ultimate Guide to the Cultural Capital of Black America.

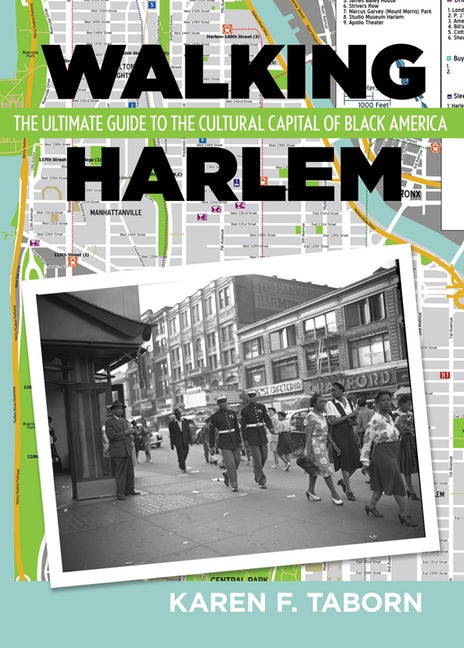

Karen Taborn published Walking Harlem in May 2018. Her training as a musician and ethnomusicologist informed her interpretation of her longtime neighborhood; she features lots of musically centered information on her tours. Harlem’s musical history is hard to rival as a quintessentially American story, and few things bring history alive more than a walking tour. Past, present, even glimmers of the future — it’s all there. With a trained eye, one learns to decode the everyday. Taborn’s clearly written and engaging guide includes maps of each tour and lots of anecdotes about the neighborhood and its culture-shaping personalities. The book is light enough to toss in a bag or pocket and easy to follow, belying the serious amount of information that it contains.

You've lived in Harlem for nearly forty years. What inspired you to write this book now?

My work on Harlem history took place within two timeframes. With a background as a jazz performer and an M.A. in jazz (NYU 1989), I was hired to provide historical research on Harlem in the early 1990s for a revitalization project initiated by the NYC Economic Development Corporation called The Striver's Center Project. Street architects, engineers, and the Harlem Chamber of Commerce were involved; together we revitalized West 135th Street between Adam Clayton Powell Blvd. and St. Nicholas Ave., where we installed a Harlem walk of fame. I did historical research on individuals honored in the sidewalk street plaques, several of which are still in place today. I completed a paper for this project called "What Made Harlem Famous" that I self-published in 1992.

After my work on the Striver's Center project, I taught a Harlem history class at the New School for a few years, then I moved on to other projects. In 2000, I went back to school and completed another M.A. in ethnomusicology at Hunter College in 2006. I always wanted to flesh out the paper I wrote for the Striver's Center project and I finally got back to my Harlem work in 2013. I wanted to write a full-length book with self-guided walking tours, archival and original photographs and I wanted to flesh out historical movements, developments and concepts that were part of African American Harlem cultural heritage. This eventually resulted in Walking Harlem.

What brought you to Harlem in 1980? Have you ever considered living elsewhere? Why or why not? How is it the same? How has it changed? Do you agree with the consensus among a growing number of people that NYC is becoming increasingly soulless? If not, how might you counter such an assertion? Could I possibly pack more questions into one question point?

I moved to New York City and Harlem in 1983 to pursue a career in jazz singing, which I actively did in the 1990s. The only other place I've thought I might want to live is New Orleans. At this point, I'm trying to visit the Big Easy once a year. Of course, Harlem and New York City have changed drastically since the 1980s. Some of the changes are good. Others not so good. When I moved there in the early 1980s, my West Harlem neighborhood was infested with drug gang warfare. The buildings on my street were covered with makeshift memorials spray-painted on the facades. I could hear automatic gunfire outside my window at night. Also, at night, I would come and go by taxis that dropped me off and picked me up on my front doorstep. This is no longer the case, and that is a welcome change. In fact, we have less congestion than Midtown or Downtown, and with our parks, Harlem--and West Harlem in particular--is a very livable.

But yes, gentrification is surely upon us. You now see European and white American tourists or residential members of our community. But certainly, Black and Brown folk are still here too, even if in somewhat diminished numbers from earlier days. I think it is imperative that those of us who know the rich history and know and understand the changes that Harlem has gone through, and continues to go through, today be active participants here in our community. There are several cultural institutions, old and new, that we should support, like the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Studio Museum in Harlem, Riverside Church, in fact all of our great historical churches, and Al Sharpton's National Action Network. There are exciting new places to support, too, like the i, Too, Arts Collective and While We Are Still Here. I am active and regularly attend or support all these institutions.

Also, we absolutely need to be involved and aware of our local politics here uptown. Whether it's our city council representative or our borough president, we need to be on their email lists and know what they are prioritizing and what their concerns are and we need to let them know what ours are. Of course, of crucial importance is that we advocate for affordable housing. The National Action Network is a good place to get involved in improving the quality of our community. But to get back to your question, "Is NYC becoming soulless? "The soul of our community to a large degree rests with what we do. We must be active in all these organizations and local government to ensure that the soul of our community is supported now and in the future.

Who is your intended audience for the book? Was it at all challenging to imagine that audience?

My intended audiences for my book are the longtime Harlem residents; new and incoming residents; tourists and visitors to Harlem; schools and university programs where Harlem history is taught. No, it wasn't too difficult to come to this conclusion.

You dedicate this book to your parents, Albert and Jeanette. How did they instill a love of your culture and history in you? How have you carried on that tradition?

I come from a family with a proud African American history. On both sides of my family, we share a tradition and a belief that a noble life lived is one in which you have given back and made the world a better place in some way. My father, Albert Taborn, was the most productive builder of black homes in 1950s Cleveland, Ohio. His company, Taborn Realty, built some 200 affordable homes for blacks during a two-year period. He was an active force combating redlining and blockbusting, and he ran his own company for the rest of his life. My mom was a passionate campaigner for racial justice. She was a member of the Baha'i Faith. She exemplified the truth that there is only one human race — the human race — throughout her life in all that she did. My mother's grandfather, Ralph Waldo Tyler, was a remarkable race man. He was a journalist in the black press and the first and only accredited black journalist to report from a foreign war: WWI. I wrote the Wikipedia article on him and I am now working on his full length biography. My mother, who passed away a couple years ago, was my biggest supporter during the first phase of my Harlem work in the early 1990s. With my writing, I hope and intend to continue in the spirit of my family tradition of educating, enlightening, and bettering my community and beyond.

What would you hope those who take your walking tours take with them during, and after, their walks?

I'd like those who take my tours to gain an appreciation of the spirit of the people of Harlem. One of the things that I learned was the incredible tenacity of black people in Harlem. Nothing was "given" to us! Everything was earned and/or fought for! Whether it was the industrious measures to get the rent paid through speakeasies and rent parties or the artists who campaigned the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for self-representation in the 1930s or several congregations that tithed their funds to build their own churches, the people themselves were the force behind making Harlem was it became and what it became known for around the world.

What do people ask you most when you lead a tour in person?

People are often curious about the people who lived here. If I can convey the absolute joie de vivre of a Harlem stride piano player like Willie “The Lion” Smith or the passion of a civil rights fighter like Asa Philip Randolph, then I've accomplished my goal.

How have your tours evolved as time has passed?

I've recently enhanced the discussion of architecture, and I'm always reading more on certain figures: Thurgood Marshall, Madam C.J. Walker, etc. So, my tours are always evolving.

In your introduction, you write, "Harlem has been known as an infamous ghetto, and more recently, Harlem has been controversially known as Manhattan's current neighborhood for gentrification. Regardless of changing demographics, it is imperative to remember and celebrate Harlem's rich history." Why is this imperative?

From time to time, I need to remind people that Harlem is so much more than mere real estate for black people. Much of our cultural legacy took place in these buildings and on these streets! So, it is one of the spaces in the U.S. that holds sacred significance for black people.

As a landscape historian and tour guide, I'm of course biased — but there really is no better way to experience / teach history than to walk through it with others. What do you learn as you move through your neighborhood? Do any recent experiences come to mind?

Every time I am at the 135th Street / 7th Avenue crosswalk I think of Zora Neale Hurston, who was assigned by her graduate studies advisor in anthropology, Franz Boas, to measure heads of those crossing by. It was the mid 1920s, and the pseudoscience of anthropometry (measuring different human body parts across "races" to classify and compare, and later, presumably, to establish racial difference among peoples) was in full force. Boas, a pioneer of cultural relativism, would have been thinking such research was shoddy and that his students' effort would disprove anthropometry's racist theories. And Zora, with her uncanny humor and comfort level among "her own people" was the only person who could likely pull it off without being shunned and ignored (at the least). I can only delight in the outrageous humor Zora must have made of this assignment.