“We Accuse”: The Harlem Rebellion, Bill Epton’s Anti-Carceral Activism, and the rise of the Surveillance State

By Joseph Kaplan

On July 16th, 1964, a mere three weeks after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, off-duty police officer Thomas Gilligan shot and killed fifteen-year-old Black student James Powell outside of Harlem’s Robert Wagner Junior High School. Gilligan claimed that he shot the 5’6” 122-pound Powell in self-defense when the teenager charged him with a knife, a claim disputed by several of Powell’s classmates.[1] While the events of that day remain contested, there is firm agreement that this was the spark for the first major urban rebellion of the 1960s.

Although an FBI countersubversive investigation found no evidence of a conspiracy behind the Harlem Rebellion, the NYPD’s intelligence unit, the Bureau of Special Services (BOSS), used their preexisting network of spies to fabricate a case against an obscure Maoist group called the Progressive Labor Movement (PL).[2] BOSS informer testimony against PL’s Harlem branch president, William Epton, formed the basis of the state’s first successful conviction for “criminal anarchy” since World War 1.[3] The infiltration of PL was the first in a quick succession of BOSS operations directed at the burgeoning Black Liberation Movement in New York City. These covert missions were marked by invasive tactics including informer infiltration, surreptitious electronic surveillance, and the use of sedition laws. Furthermore, they were carried out by young, ambitious Black undercover officers trying to prove themselves to an overwhelmingly white police force. Bill Epton’s conviction for advocating criminal anarchy represents an understudied and important chapter in the intertwined history of 1960s urban rebellions, anti-carceral activism, and the growth of the surveillance state.[4]

After leaving the Communist Party in 1962, Epton, a lifelong Harlemite and ardent Communist, organized a branch of PL around issues that directly impacted his community, particularly police brutality. The small, all-Black branch stood out within PL. As one member noted, “this is not a black organization… it’s black, all right, here in Harlem, but outside, in other cities, the membership is often largely young white kids, students, many of them from middle class families.”[5] Harlem PL’s Black membership, dedicated leadership, and militant opposition to police brutality made it a small but radical part of the city’s Black Freedom Movement. It also made it a target for BOSS infiltration.

Joining Epton and five regular members, the final recruit into the branch was BOSS agent Adolph “Abe” Hart. A Black man from the hardscrabble Pittsburgh area, Hart yearned for the respect and stability of a job in law enforcement but faced hurdles due to the racism rampant in police culture. Before joining BOSS, the Washington DC police rejected Hart for allegedly failing his physical exam, despite playing football at Franklin University and having just returned from a tour of duty in Korea. He got his first opportunity in law enforcement when BOSS began hiring Black officers to infiltrate the growing Black Liberation Movement. Initially sent to infiltrate Malcolm X’s Muslim Mosque No. 7, Hart was reassigned to the Progressive Labor Movement in November of 1963.[6] He spent the next eight months getting as close to Epton as possible. When the Rebellion erupted, Hart was deeply embedded, and his intelligence reports formed the basis of the state’s case that Epton was responsible for the disorder.

Image taken from Life, July 31, 1964, 16. See also: Subversive Influences, 963. Hart Exhibit No. 12

When Powell was murdered, PL was already engaged in a campaign against police brutality, particularly the case of the “Harlem Six,” and his death sparked an even greater flurry of activity.[7] The day of the murder, PL issued pamphlets that put Powell’s death in the context of “the police war on Harlem.”[8] They circulated flyers listing recent victims of police violence to which they added his name. PL members then found a picture of the officer who shot Powell and emblazoned his face onto another flyer that read, “Wanted for Murder: Gilligan, the Cop.” These were distributed throughout Harlem, becoming so ubiquitous that scores of demonstrators carried them as they marched on the 28th Police Precinct.

BOSS responded aggressively to PL’s anti-carceral campaign. On July 18th BOSS monitored a PL rally on the corner of Lenox Avenue and W. 115th Street. Along with Hart, Patrolman Alonzo Stanley and Detectives John Rivera and Francis Koopman were on hand. While Stanley patrolled, Rivera wore a wire transmitting to Koopman in his patrol car a few blocks away. This surveillance enabled BOSS to produce a transcript of Epton’s comments. After discussing the racism endemic to the legal, military and educational systems, Epton called for “smashing the state.” At a climactic moment he declared, “in the process of smashing this state, we’re going to have to kill a lot of these cops, (and) a lot of these judges.”[9] While his language was inflammatory, the rally ended without incident at 6:00 PM, as reported by BOSS detectives on hand. While violence did erupt that night, it was hours after Epton finished speaking. In fact, rather than informing his superiors of an imminent subversive plot, Hart’s handler called him in the middle of the night ordering him to race to Harlem to be BOSS’s “eyes and ears” amidst the unrest.[10]

Epton, center, leading a march at 116th and Lenox Avenue in defiance of a police injunction against demonstrations a week after the unrest began. Police arrested Epton and his lawyer Conrad Lynn, right, moments after this picture was taken. R.W. Apple Jr., “Protest Leaders Seized in Harlem: Two Leftists Arrested After Defying Police and Ignoring Pleas for Negro Unity,” New York Times, July 26, 1964, page 1.

After days of intense surveillance, Hart’s superiors hoped to press forward with charges, but they were told that the “brass needed more information before they could bring Epton… to trial.”[11] Determined to pin blame for the violence on Communist agitators, BOSS resorted to more invasive tactics. On July 21st, Hart was called to the contact office where Detective Koopman fitted him with a Minifon recording device designed to look like an ordinary inexpensive tie clasp. Armed with a wire, Hart hoped to get Epton to admit to printing an uncredited pamphlet circulating through Harlem entitled, “Harlem Freedom Fighters: How to Make a Molotov Cocktail.” Hart averred that PL was printing the leaflets, but he was never able to ensnare Epton into admitting as much on tape. Epton was eventually arrested on Saturday the 25th for disorderly conduct when he defied an injunction against demonstrations in Harlem. Finally in custody for an articulable crime, Epton’s role in the Harlem Rebellion came to an end. However, his ensuing trial for “criminal anarchy” revealed BOSS’s furious attempts to blame Black radicals for the unrest caused by police violence.

On August 3, 1964 William Epton was summoned by a grand jury, known as the 2nd August Grand Jury, stemming from his arrest at the abortive march on July 25th. The 1st August Grand Jury, convened to investigate the charges against Lt. Gilligan, took less than one month to clear the 6’2” 200-pound Gilligan for shooting a fifteen-year-old boy.[12] In contrast, Epton’s grand jury conducted a ten-month investigation into his role in the rebellion, subpoenaing dozens of witnesses, many of whom were jailed for contempt of court, finally rendering a guilty verdict on a superseding indictment for advocacy of criminal anarchy in December of 1965.[13] The investigation relied on coercive practices such as harassing witnesses with subpoenas, while Epton’s conviction was secured through unsupported and inconsistent testimony from Hart.

The trial, which began in November of 1965, exposed major inconsistencies in Detective Hart’s testimony, raising serious questions about the intent and propriety of his investigation. The case hinged on Hart’s evidence, and Epton’s lawyers presented a compelling case that he fabricated evidence to assure a conviction. Pretrial discovery and cross examination revealed that Hart’s own written reports, of which there were hundreds, often conflicted with or failed to corroborate his testimony in court. For instance, cross examination revealed that Epton’s alleged call to suck cops into side streets where they could then be attacked from rooftops had in fact “been made by a man called ‘Ace.’”[14] Among the more troubling discrepancies was Hart’s claim that William McAdoo, Epton’s second in command, had showed he and Pernella Wattley how to prepare a Molotov cocktail in the PL office on July 19th. The defense called Mrs. Wattley as a corroborative witness where she proved that on the night in question she had attended a funeral at Perkins Undertaking Parlor in the presence of numerous witnesses. This testimony went uncontroverted by the prosecution.[15]

Even more troubling, Epton’s defense team showed that Hart may have acted as an agent provocateur. Hart took part in what the court deemed “overt acts,” such as helping to prepare a leaflet entitled “Stop the Cops” on the morning of July 20.[16] At times, Hart’s actions went beyond merely going along with the group; he actively urged violence. In an exchange deemed “not pertinent to the investigation,” Hart was recorded, on his own wire no less, telling PL members, “it’s still pathetic when you realize people are still throwing bottles, when all you got to do is put gas in the bottle. Certainly they’re going to throw bottles anyhow!”[17] Thus, Hart’s wire not only failed to show a connection between Epton and the Molotov leaflet, the only person heard on tape urging their use was Hart himself. Eventually, the Molotov testimony was thrown out as irrelevant, and the judge acknowledged that Epton could not be connected with “the act of any person who participated as a rioter.”[18] Nevertheless, the trial continued.

Outraged by the absurd, Kafkaesque charade, Epton and his supporters used his trial to unmask the repressive nature of US capitalism that lay behind a liberal Cold War façade of procedural fairness. The first week of the trial, the court received a letter from Cheddi Jagan, Premier of British Guiana. Connecting the Northern legal system to institutionalized segregation in the South, he argued that Epton’s trial revealed “the failure of U.S. society to eradicate Jim Crow and discrimination.”[19] On December 9th, over 400 people gathered at the Carleton Terrace Ballroom to hear Civil Rights activists speak on Epton’s behalf. Epton himself headlined the event, denouncing the police as the real criminals and vowing to “put THEM on trial.”[20] After being found guilty of conspiring to riot, conspiring to overthrow the government and advocating its overthrow on December 21, 1965, Epton did just that.

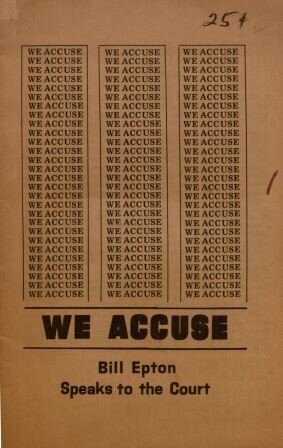

Epton’s speech at his sentencing hearing was reproduced as a PL pamphlet entitled “We Accuse.” Anna Franz, “Ripped From the Headlines…” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library, April 21, 2015, https://library.law.yale.edu/news/ripped-headlines.

In a brilliant stroke of political theater, Epton turned his sentencing hearing into a public forum on the racist history of the legal system. To the delight of his sixty supporters crowding the courtroom, Epton unleashed a forty-five-minute tirade against American imperialism that was reprinted as a PL publication entitled “We Accuse: Bill Epton Speaks to the Court.” Eschewing appeals to his Constitutional right to free speech, he framed his prosecution as a component of America’s drive to suppress radical movements around the world. Connecting the repression he faced to America’s position as a global counterinsurgent force, he declared that the United States used its “para-military police force” to “guarantee its home base, silence dissent and whip its own people into line.”[21] As Epton finished, the courtroom burst into applause while Judge Markewich sprang to his feet and ordered his supporters cleared from the room. After a paternalistic lecture, the judge sentenced the husband and father of two to one year in prison.

Although the Harlem Rebellion has received renewed historical attention, scholars have overlooked BOSS’s infiltration of PL and scapegoating of Bill Epton.[22] Not only was this an important episode in the life of an iconoclastic Harlem activist, it portended an insidious expansion of state surveillance epitomized by the FBI’s illegal Counterintelligence Program (COINTELPRO) and BOSS’s infamous arrest of twenty-one Black Panthers on fabricated conspiracy charges in 1969.[23] Furthermore, Epton’s story rings familiar in our current moment as anti-Communist conspiracy theories proliferate unchecked in Right-wing political discourse and the Biden administration expands state surveillance under the guise of combatting domestic terrorism.[24] Given that the FBI opened at least 300 domestic terrorism investigations in response to protests over the murder of George Floyd last summer, Bill Epton’s incarceration should serve as a reminder that a bloated surveillance state has historically exposed anti-carceral activists to criminalization, surveillance, and charges of sedition.[25] Epton’s story offers the sobering lesson that an anti-carceral movement must encompass a robust critique of state surveillance, both in principle and for its own protection.

Joseph Kaplan is a doctoral candidate at Rutgers University. He studies the intersection of 20th Century African American political radicalism and the growth of the postwar surveillance state. His forthcoming dissertation analyzes the NYPD's use of informer infiltration to monitor and disrupt Black radical organizations.

[1] Powell’s height and weight cited from Adolph Hart, Memoirs of a Spy (Bloomington: 1st Books, 2004), 59. For more on the rebellion itself, see: Michael Flamm, In the Heat of the Summer The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017); and Christopher Hayes, “The Heart of the City: Civil Rights, Resistance and Police Reform in New York City, 1945-1966,” unpublished dissertation, Rutgers University, 2012. For a post facto analysis of the incident, including the findings of an independent CORE investigation, see: U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, “James Powell- Notice to Close File,” File No. 144-52-1138, https://www.justice.gov/crt/case-document/james-powell-notice-close-file.

[2] The Bureau of Special Services, also known as BOSS or BOSSI, was the NYPD’s clandestine intelligence unit tasked with three main functions: monitoring labor unrest, protecting visiting foreign dignitaries, and surveilling potentially subversive actors and organizations. Founded in 1904, BOSS was one of the United States’ earliest political police forces, preceding the advent of the Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI) by four years. For a general overview of BOSS’s history see: Anthony Bouza, Police Intelligence: The Operations of an Investigative Unit (New York: AMS Press, 1976). For critical accounts of the unit focused on its role as a “Red Squad,” the generic name for countersubversive police units, see: “Red Squad,” directed by Joel Sucher, fl. 1972-2012 (New York, NY: Pacific Street Films, 1972), 41 mins; and Frank Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), Chapter 5.

[3] The statute had last been enforced against Communist leader Benjamin Gitlow in 1919. See: Jack Roth, “Epton Gets Year in Anarchy Case,” New York Times (New York: NY), Jan 28, 1966; Michael Flamm, In the Heat of the Summer, 212-213; and TJ English, Savage City: Race, Murder, and a Generation on the Edge (New York: Harper Collins, 2011), 198.

[4] I use the term “anti-carceral activism” to refer to a set of punitive practices and policies around which activists at this time mobilized. This included campaigns against police brutality, police corruption, poor conditions in prisons and jails, as well as political repression and surveillance. It should be noted that activists at this time did not use the language of “carcerality,” but rather saw their protests against unreasonable police power as part and parcel of the fight for community control, self-determination, and self-defense at the heart of New York City’s Black Liberation Movement.

[5] Warren Hinckle, “The March that Failed,” Ramparts, October 1964, 31.

[6] Adolph Hart, Memoirs of a Spy, 27. “Subversive Influences in Riots, Looting and Burning:” hearings before House Committee on Un-American Activities, 90th Cong., 2nd sess., 1968, 930.

[7] The “Harlem Six” were a group of young Black men who were beaten, arrested, imprisoned, and tortured by the NYPD after an incident involving an overturned fruit stand, an event known as the “Harlem Fruit Stand Riot.” The case was most famously documented by James Baldwin in his “A Report from Occupied Territory,” The Nation, July 11, 1966. However, Epton’s branch of PL was at the forefront of community efforts to call attention the injustice. Epton helped organize the boy’s mothers into an advocacy group known as the Mother’s Defense Council. Furthermore, the Committee to Defend Resistance to Ghetto Life (CERGE), a group Epton also led, published an expose about the case entitled “A Harlem Mother’s Nightmare,” written by Selma Sparks, a contributor to PL’s newspaper, Challenge.

[8] This phrase is taken from the cover of PL’s publication, Challenge, a week before the uprising. See also: “Leftist Movement Opens Harlem Drive,” New York Times, June 15, 1964.

[9] Subversive Influences in Riots, Looting, and Burning, 952. Hart Exhibit No. 2.

[10] Adolph Hart, Memoirs of a Spy, 80, and 82. Hart never reported any subversive plot to stoke a rebellion before the actual uprising. In fact, BOSS’s own records indicate that the rebellion began at the 28th Precinct when a bottle was thrown and “the area was ordered cleared by police. CORE leaders then ordered their members to sit down, thereby sparking subsequent disorder.” See: New York City Municipal Archives. New York Police Department Intelligence Records, 1930-1990. Box 30, Harlem Riots, Folder 4, “Events Leading to Riots.”

[11] Adolph Hart, Memoirs of a Spy, 145.

[12] Gilligan’s exoneration was met with outrage by the Black community. Linking urban policing to Southern lynch law on a continuum of anti-Black violence, Harlem housing rights activist Jesse Gray called the Grand Jury’s verdict “the greatest whitewash since Emmett Till.” See: “Negroes Denounce Gilligan Whitewash,” New York Amsterdam News, September 5, 1964. See also: Progressive Labor Party, “We Accuse: Bill Epton Speaks to the Court,” 2. David Halberstram, “Jury’s Exoneration of Gilligan Scored by Negro Leaders,” New York Times, September 2, 1964.

[13] Frank Donner, “Aftermath to Harlem Riot: The Epton Anarchy Trial,” Nation, November 15, 1965, 355-372, 356. Progressive Labor Party, “We Accuse: Bill Epton Speaks to the Court,” 5.

[14] Records and Briefs, New York State Appellate Division, New York State Supreme Court Appellate Division: First Department. The People of the State of New York, Respondent, against, William Epton, Appellant. Appellant’s Brief, 12. Hereafter, New York v. Epton.

[15] New York v. Epton, 38.

[16] New York v. Epton, 20. Peo. Ex. 15. “Overt acts” refer to specific actions intended to further the goals of a criminal conspiracy. In this case, the prosecution held that Epton’s First Amendment protected speech and writings constituted overt acts in furtherance of a conspiracy to overthrow the government of the state of New York. This was a dangerous and legally dubious claim. Although Epton exhausted his appeals in 1968, Supreme Court Justice William Douglas contended in a dissenting opinion that “the use of constitutionally protected activities to provide the overt acts of conspiracy convictions might well stifle dissent.” One year later the Supreme Court ruled that speech could only be deemed an overt act if it “is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action.” See Epton v. New York, 390 U.S. 29 (1968), and Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969).

[17] New York v. Epton, 19.

[18] Richard Johnson, “Epton is Cleared on 1 of 4 Counts,” New York Times, December 11, 1965.

[19] Progressive Labor, “We Accuse,” 36. Richard J.H. Johnson, “Prosecution Declares Epton Encouraged Riots,” New York Times, November 30, 1965.

[20] “’Free Bill Epton,’” Challenge, December 21, 1965, 5.

[21] Progressive Labor, “We Accuse: Bill Epton Speaks to the Court,” 7, 11.

[22] For the most prominent recent works on the Harlem Rebellion see: Michael Flamm, In the Heat of the Summer: The New York Riots of 1964 and the War on Crime (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017); Christopher Hayes, “The Heart of the City: Civil Rights, Resistance and Police Reform in New York City, 1945-1966,” (Ph.D diss., Rutgers University Press, 2012); Clarence Taylor, Fight the Power: African Americans and the Long History of Police Brutality in New York City (New York: New York University Press, 2019); CH 5; and Garrett Felber Those Who Know Don’t Say: The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), CH 5. While these works have added important new insights into the Harlem Rebellion and its implications for both electoral politics and anti-carceral activism, Epton has been relegated to a minor footnote in the drama despite the state’s official claim that he was personally responsible for the violence.

[23] On COINTELPRO see inter alia: U.S. Senate. Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, S. Rep. 94-755, 1976; Athan Theoharis, Spying on Americans: Political Surveillance from Hoover to the Huston Plan (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978); David Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence (Berkeley: University of California, 2004). On the case of the “Panther 21” see: Peter Zimroth, Perversions of Justice: The Prosecution and Acquittal of the Panther 21 (New York: Viking, 1974); Sekou Odinga, Dhoruba Bin Wahad, Shaba Om, and Jamal Joseph, Look for Me in the Whirlwind: From the Panther 21 to 21st-Century Revolutions (Oakland: PM Press, 2017).

[24] The counterterrorism solutions offered by the neoliberal Biden administration’s “National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism” echo longstanding trends in the centralization and professionalization of intelligence gathering; trends accelerated by the “War on Terror.” Recommendations include a pledge to increase intelligence sharing across Federal, State and local jurisdictions, rebranding of the controversial and discriminatory “Countering Violent Extremism” (CVE) program, and directing $77 million in Department of Homeland Security outlays to local law enforcement initiatives aimed at countering extremism. See: White House Briefing Room, “Fact Sheet: National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism,” June 15, 2021, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/06/15/fact-sheet-national-strategy-for-countering-domestic-terrorism/. On the principled opposition of Muslim activists to the Biden administration’s domestic extremism program, see: Cody Bloomfield, “Muslim Activists Call BS on Biden,” Defending Rights and Dissent, July 22, 2021, https://www.rightsanddissent.org/news/muslim-activists-call-bs-on-biden/, and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0jg318wh_9U&t=4s.

[25] Masood Farivar, “Hundreds of Domestic Terrorism Investigations Opened Since Start of George Floyd Protests, Official Says,” Voice of America News, August 4, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/usa/race-america/hundreds-domestic-terrorism-investigations-opened-start-george-floyd-protests.