What's in a Name...?

By Benjamin Feldman

What's in a name? goes the popular refrain. Redolence, I say. Taste and smell. When I encounter something delicious, I’m often tempted to take a Dagwood-sized bite. Sometimes, though, caution dictates just a nibble. Especially when I walk through a burial ground.

Novigroder Young Mens Benevolent Association—Erected August 30, 1918

Fear whacked me right in the face as I ventured across Richmond Avenue in Graniteville, Staten Island a few weeks ago. Don’t Walk cried the red khamsa (five-fingered hand) on the street corner, warning me not to dare scurrying across the newly-paved boulevard on my way into Baron de Hirsch Cemetery. Graveyards can be creepy places, filled with sadness and prematurely-ended lives. Unkempt lots and forgotten tombstones, vandalized memorials fill so many Jewish graveyards. I already knew my destination to be no exception.

It’s another country out there. The sidewalks were empty; cars rule the road in the land where John McCain carried the day. I walked past Castellano’s House of Music, its cheesy signs blaring ads for wannabe metal-heads who amp up their Fenders and pound on trap sets all over Richmond County, dreaming Springsteen sugarplum dreams. Salinger’s “DeDaumier Smith’s Blue Period” somehow comes to mind. New York City overflows with strange juxtapositions: across the street from this local Juilliard sits stone-cold quiet Baron de Hirsch Cemetery, with its thousands of permanent residents.

Founded by the philanthropy of its British railroad-magnate namesake, the burial ground is home to the sacred plots of dozens of Jewish burial societies. Many were part of landsmanshaft (homeland kinship) societies, owned by the benevolent organizations of immigrants from Eastern European cities and towns. Chernigov, Pistyn, Tysmienica, and many, many others are represented in force. Other societies served vanished Jewish congregations from Hudson County, New Jersey. The ner tamid, the Eternal Light, long ago flickered out behind the pulpits of nearby synagogues: Gone are the congregations of Tifereth Israel of Jersey City, ditto, Adas Israel of Bayonne.

Jews were joiners: from the earliest days of the Eastern European immigration, the drive to assimilate, to become all-rightniks, was a monstrous thirst, slaked by becoming part of a club. The burial societies give witness: The stone gates list, in Yiddish and English, the names and titles of the many. Despite the ocean voyage, (most times in steerage) at the sweatshop you were still a galley slave; nothing had really changed since the era of Pithom and Ramses. But here, in America, you could be someone: an officer, a dues-payer, a member in good standing. Deracination barreled ahead. International organizations that admitted Jewish chapters are well represented at Baron de Hirsch. The Odd Fellows and Knights of Pythias chartered many Hebrew lodges. Officers, past and present, gate committee members, recording secretaries, financial secretaries: all are listed, their yikhes (pedigree) recorded.

The persecution, both economic and religious, that drove so many millions of Jews from Eastern Europe to America, also tarred them with the name of anarchists. Belief in Jewish complicity in events such as the infamous 1886 Chicago Haymarket Square bombing was widespread. Left-wing Jewish agitators in Europe and the USA were a mortal danger to those of the chosen people who wanted nothing to do with socialist politics. So names were chosen to cloak the many centrist tailors with the flag. The William McKinley Benevolent Association at Baron de Hirsch is only one example. Daniel Webster, James A. Garfield and other Americans of unquestionable patriotism and integrity were embraced whole-hog, everything but the treyf (un-kosher) squeal put to good use. I wonder if the old Yankee Doodles would have minded had they known to what assimilatory advantage their good names would be put?

In Honor of Di Goldene Medine, The Golden Land

Nearby the cemetery, the arching Bayonne Bridge leads from nowheresville to ek velt (the end of the world): Bayonne, New Jersey is literally a corner, a narrow peninsula jutting out into Newark Bay. A bridge of sighs to the world to come, this graceful steel span carried countless funeral processions that led across the Kill Van Kull from Hudson County to the Staten Island final resting ground. In the late 19th and early and mid-20th centuries, Bayonne was home to a significant Jewish population. Who knew? 1

Three times I’ve visited Baron de Hirsch in the past 18 months. What draws me back there? It’s the promise of uncovering unknown histories, revivifying lives that are lost to our collective memory. And in some sense connecting to relatives I never knew. Just this past visit I stared grimly at one of the freshest graves, a polished black granite tombstone of a Soviet Jew named Alexander Dikshteyn, containing his portrait, photo-etched on the stone. Their custom seems so un-Jewish to me, but among secular Jews there is long precedent. In Mount Hebron cemetery in Queens, one sees porcelain photo medallions on many graves, sadly deteriorated after seventy and more years of weather. But then I was put off by a different reason… The unfortunate Russian’s first day on earth was all too familiar: June 24, 1952. Intimations of mortality shivered through my frame. That’s my birthday. Maybe this whole project was DOA.

I fought back, though: riches beyond measure were strewn all over; each society’s plot a mystery of place and affiliation to be untangled from the vines of neglect. Inscriptions in Hebrew, Yiddish, English, Russian, even the Albanian tongue, decorate the stones and portals of fenced spaces. Cyrillic and Arabic effloresce on many of the newer markers. Ashkenazic Jews have not dominated the count of daily interments in Baron de Hirsch in many years.

In A Field Not Far From The Tower of Babel...

Despite the wilderness of unkempt gravesites, this sacred Jewish resting ground is covered with a holy cloth. Much like the gold-trimmed, wine-velvet fabric that bedecks the table on which Torah scrolls are laid to be read in the synagogue, a blanket of history covers the entire site. No matter the six-foot tall reeds that obscure all stones in the most-neglected plots; no problem the broken, un-mended gravesites: The dishabille of the place amidst the brilliant autumn colors sharpened my eyes and then delivered a huge reward.

Tkhies hameysim, the raising of the dead, can be done with very large groups. At Baron de Hirsch, whole populations can be levitated. Jewish bagel bakers rose before my eyes. How many years have gone by since they did it, unionized Jewish men, in numbers great enough to organize, baking our favorites, forming a lodge?

The day before my Staten Island visit I’d come across a listing of archives of fraternal organizations at the YIVO archives. One title stood out, almost laughable in these times. Ershte Beygl Beker Krankn Untershtitsung Farayn. First Bagel Bakers Sick and Benevolent Society. Warm aromas filled the air: poppyseed, salt, garlic, everything: Perhaps I could find a remnant of this group’s existence. My question would be answered: What’s in a name?

Then next day I returned and walked the cemetery, totally naïve, unsuspecting, then boom! A piece of mazl (good luck) came my way: Leaning against the granite columns at the entrance to the plots of the United Varshaver Sick Benefit Society were three rusted iron gates, a pair and an odd one. The single belonged there, the other two not. The entrance to the world to come which the matched pair guarded lay immediately across the path. The name on the iron mirrored the inscription of the pediment cater-corner: Ershte Beygl Beker Krankn Untershtitsung Farayn.

Before the 1937 formation of Bagel Bakers Union Local 338, smaller organizations served the needs of this critical trade. Bagel bakers belonged to Locals 505, 507 and 509 of the larger Bakery Worker’s Unions. Jewish Bakers Associations were organized in the Bronx and Brownsville Brooklyn. Membership meetings of many groups were held in downtown halls where not a trace remains today of their glorious union past.

Local 31 of the Jewish Bakers Union was formed on the Lower East Side in 1885, but it was short lived, even after its resurrection in 1890. It’s no wonder a sick and benevolent society was needed. Bagel bakeries on the Lower East were basement gehennas of filth and squalor, where the men labored bare-chested among roaches and mice fourteen hours a day. The heat, fatigue and germs surely shortened many bakers’ lives. For $665 the First Beigel Bakers Kranken Unterstuetzungs Verein of 145 Suffolk Street acquired a place in the country for its members to take a final break. Section G, Lots 1100-1109 would be the site, Baron de Hirsch the resting place.

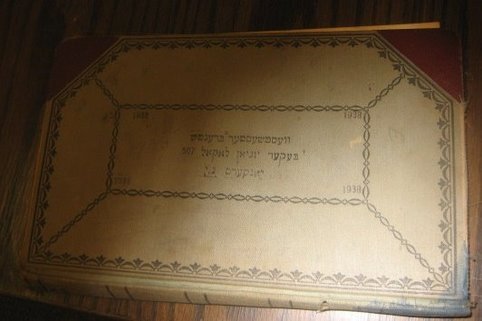

1938 Ledger of "Westchester Branch, Bakers Union Local 507, Yonkers, NY"

1937 saw the formation of Local 338, its offices located at 111 East Houston Street (sadly now demolished) and at other times at 121 University Place. Membership in Local 338 was nepotistic. Sons and other male relatives were accommodated. Others not. Closely affiliated with the United Hebrew Trades movement and other large-scale labor organizations, Local 338 pushed hard to make all bagel bakeries union shops. The invention of bagel-baking machinery and the rise of Lenders Bagels in West Haven, CT in mid-century spelled the end of Local 338, though. An industrial irrelevancy, its remnants merged with Bakery Workers Local 3 in the early 1970s. From the Forverts, n.d.: “Bagel Bakers Boss Leybovitz Has Settled With the Union”—The Bagel Bakers Union Local 338 makes known that the protracted strike against Boss Leybovitz from the Rockaway Bagel Company is settled with a victory for the union. Boss Leybovitz, whose bakery is located at 4814 Rockaway Boulevard, Rockaway Beach, has signed a contract with the union agreeing to all the union requirements…

****************

The names on the Bagel Bakers’ tombstones smelled as rich and tasty as the dough they rolled: M. Stein, Helk Ziperstein, Yankev Shoykhid (a misspelling of shoykhet?: Jewish kosher slaughterer) Where did these men live? How long were their days? Did they love to play pinochle? Bet on horses or drink? I’ll keep working the archives for some answers, but next time I visit the graveyard, I’m taking precautions: I’ll carry a box of Sterling Kosher Salt. Every three steps I’ll stop and pour some. A handful to throw over my shoulder like my elterbobe (my old great-grandmother) did for good luck. Dusk was falling as I walked along Baron de Hirsch’s Section G paths. It was nearly closing time when I spotted bagel baker Harry Fertel’s stone. Again, a chill grabbed me. “Maybe I should high-tail it outta here,” I said to myself quietly. Harry Fertel died the day I was born.

Benjamin Feldman has lived and worked in New York City since 1969. His essays about New York and Yiddish culture have appeared on-line in The New Partisan Review, Ducts literary magazine, and in an earlier edition of The Gotham History Blotter. Much of his work can be read on his website, The New York Wanderer. His books include Butchery on Bond Street—Sexual Politics and The Burdell-Cunningham Case in Antebellum New York and the forthcoming Call Me Daddy—The Lives and Loves of Edward West Browning, New York’s Jazz-Age Lecher King.

Acknowledgments:

For intellectual guidance on the broadest scale in the preparation of this article and ongoing inspiration I am indebted to my friend Benjamin Sadock. His contributions to this effort are second only to the guidance and support of my wonderful wife and partner of 32 years, Frances Stern. I am also tremendously grateful to Baron de Hirsch Cemetery’s brilliant and kind Superintendent and General Manager Raphael Bochbot, to Leo Greenbaum, chief archivist at YIVO, Larry Gutterman of Gutterman’s Funeral Home of Bayonne, NY and the members of HudsonJewish.org who so rapidly assisted me in my research; to Gail Malmgreen, Associate Head for Archival Collections and her staff at Tamiment Library/ Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at NYU, and authors Matthew Goodman (at work on a screenplay about Local 338 and bagel making in general) and Maria Balinska (who just published a marvelous account of that most Jewish of foods entitled simply The Bagel.

Jack Klugman as Ben Patimkin in Goodbye, Columbus jumps to mind: The pater familias of a Newark, New Jersey plumbing supply business might well have grown up among the predominant Italians in 1920s Bayonne, decamping for a leafy cul de sac in Bergen County with his two daughters, wife, and Carlotta the black maid. Suddenly it all jumps to life: It’s only yesterday I heard Jack squawk to Ali MacGraw during her boyfriend Richard Benjamin’s first visit to the family’s overloaded dinner table “She eats like a bird !” and to Michael Meyers (when her brother, Mr. Ohio State super-jock, helping out for the summer at the family’s plumbing supplies yard tried a bit of workers’ schedule juggling management consultancy and was shot down by his high-school drop-out Dad): “We all go to lunch at the same time !” A scene in Baron de Hirsch as an old family member is gently lowered into their grave could well have been cut into that sweet film, showing us all whence we came and where we’re going. [↩]