When the Media Elite Threw Their Fedoras into the Ring for Women’s Rights

By Brooke Kroeger

Key to the momentum that propelled the 70-year-old women’s suffrage campaign to victory was the support this “despised” cause attracted from members of New York City’s media establishment, both in their public behavior and in the pages of the mainstream publications they wrote for or controlled. Trolls on the parade line took aim at their masculinity, but what today might be called their “liberal media bias” passed without apparent notice. In the 1910s, editorial dispassion as a value was not quite yet a thing.

Publishers, editors, stylish writers, and reporters were plentiful in the leadership and ranks of suffrage organizations that emerged in the pivotal decade leading up to the 1919 passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and its ratification in 1920. These men not only wrote or featured pro-suffrage coverage in their magazines and newspapers, but they marched, gave speeches, and lobbied the legislatures and executive branches of government for the cause.

George Harvey was editor and publisher of both Harper’s Weekly and the North American Review when he joined the Equal Franchise Society and became its third vice president at the end of 1908. This was a group of women and men meant to take the organized work of suffrage “more into the ranks of society,” and to give the dazzling socialite Katherine Duer Mackay her own platform within the larger women’s suffrage campaign. At the time, she was married to the wealthy telecommunications magnate Clarence Mackay, chairman of the board of Postal Telegraph and Cable Corporation and president of Mackay Radio and Telegraph Company, but it was she who brought the marriage its New York social cache. (Katherine's father, William A. Duer, her father, appears on page 25 of the 1887 New York Social Register two years before Katherine's marriage, for example, but on page 50, no Mackays.)

Like others among the magazine and newspaper leaders who supported the cause, Harvey’s real function within the group was clear. In January 1909, he committed the headline-worthy act of hosting a table at the luncheon banquet where Mackay gave her inaugural speech. The anti-suffrage — but no less Blue Book-respecting — New York Times playfully declared Harvey’s chivalrous display the “first time a man ever held that position in a similar gathering in this city.” The following month, the Times featured not the top leadership in Mackay’s organizational pyramid, the women, but a quartet of men from further down the membership ranks. “Well-Known Men Advocate It” was the headline over explanations from Harvey, Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, the philosopher John Dewey, and the director of the People’s Institute, Charles Sprague Smith. No surprise that the opinions of important men mattered more.

A month later, on March 13, 1909, when Mackay’s group was barely three months old, Harvey’s own Harper’s Weekly devoted four pages of puffery to the group he had joined under a fetching photographic portrait of its elegant leader, and below, some of the society dames she had attracted as members. The writer gushed about the group’s “irresistible advance,” at Mackay’s ability to attract “so many persons of prominence in the social, professional, and financial worlds,” and at “the rapidity with which the movement for woman suffrage is spreading.” Very soon, in fact, this also became true.

The following year, in November 1909, came announcement of a new Men’s League for Woman Suffrage of the State of New York, replete with charter, constitution, and a membership roster of 150 A-list New York men, all with high-impact name recognition in the city or state. Harvey was on its advisory committee alongside Hamilton Holt, the publisher of the Independent, and William Dean Howells of the Atlantic, who was a first vice-president. The man who inspired the league’s creation, Oswald Garrison Villard, editor and publisher of the New York Evening Post and the Nation, was on the executive committee.

Holt

Howells

Villard

How involved were they? As early as 1894, the Times quotes Howells espousing the right of women to vote. In February 1909, he was also the first man to sign a pro-suffrage “special authors’ petition” being prepared to send to Congress from the offices of NAWSA, the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Copies of the petition went out to every author in the country with a request that it be signed and mailed back to NAWSA for cut-and-paste compilation.

When the first troop of Men's Leaguers marched for votes for women in the second annual New York City suffrage parade on May 6, 1911, the Chicago Tribune noted in the following day's paper how many of them were "art editors, dramatic editors, associate editors, and other literary persons from the muckraking belt."

Holt committed seven photo-filled pages of the October 12, 1911 issue of his Independent to a suffrage-boosting roundup, titled, “Spectacular Woman Suffrage in America.” Villard’s New York Evening Post did its part in front section and opinion page coverage and in personal lobbying efforts to the leadership in Albany and Washington, DC.

In March 1913, the day after the suffrage parade that preceded President Wilson's inauguration in Washington DC, the reporter Nellie Bly recorded the experience for the New York Evening Journal (the newspaper's editor at the time, Arthur Brisbane, was a suffragist, too). From her horseback perch as a member of the procession's ceremonial honor guard, she had a particularly good vantage point. Among the many things that struck her was an unusual choice by New York's the pilgrimage hike leader, Rosalie Jones, in her bread-and-butter list of people to thank. Bly wrote:

Down in Baltimore, when the wonderful, loveable William McCombs pulled off something which gave Mr. Wilson a free ticket to Washington, somebody got up and thanked everybody and everything, from the sparrows in the streets to the stars in the heavens for courtesies and aid extended to the convention, but he never mentioned the press and the telegraph operators.

"Thank the press," I told him when he came off the platform. "They are the ones who let the country know what you were doing. They created the interest in your proceedings. They have made your names known."

"No one thanks the press," he said.

But Rosalie Jones was clever enough to know that without the power of the press she and her pilgrims could have hiked along like so many hoboes and the struggling few who observed them on the way would not have known or understood. The power of the press has made her pilgrimage known throughout the United States and so much so in the Washington Post one hears of the suffragettes all of the time to the exclusion of the Presidential inauguration.

Take a good look at the magnificently illustrated all-suffrage number of the popular satirical magazine, Puck, dated Feb. 20, 1915. Note especially those listed as “Honorary Editors” in the house ad for the issue that appeared a week earlier.

Listed along with Harvey and his two widely read magazines were editors and publishers of Munsey’s and

Everybody’s. From the major newspapers, top editors of the New York Journal, the New York Evening Post, the New York Tribune, and the New York World also lent their names. All these publications were as suffrage-friendly as the New York Times was not, and all the men named were loosely or very closely affiliated with the New York Men’s League.

See the legend in the upper right-hand corner of the cover, above Rolf Armstrong’s illustration, “The Mascot”? It touts “Editorial Direction” for the issue from six New York state suffrage organizations, including the Men’s League with its formidable editorial firepower. Inside, the regular editors of Puck vowed to pump for suffrage until the vote was won.

At about this time, the Men’s League put muscle into generating publicity for the New York State suffrage referendum campaigns of 1915 and 1917. The maestro of this major promotional push was George Creel, who stayed in the position until just before President Woodrow Wilson tapped him, in April 1917, to head the country’s World War I propaganda and censorship effort, the CPI, the Committee on Public Information. Along with his administrative duties, Creel sparred with the anti-suffrage forces in an attention-getting letters-to-the-editor campaign in the Times and in major reported take-outs for Pictorial Review (“Chivalry Versus Justice,”), the Delineator (“Measuring Up Equal Suffrage,” with Judge Ben B. Lindsey), and in The Century (“What Have Women Done With the Vote?”)

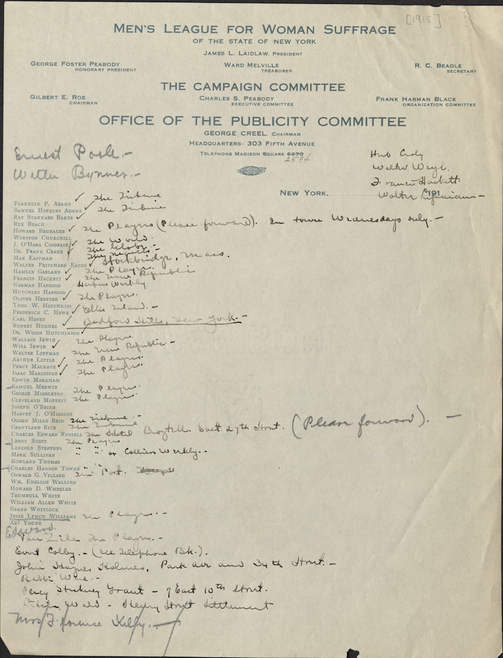

Check out the names listed in the margin of the Men’s League Publicity Committee stationery, the reporters, writers, poets, playwrights, publishers, and editors who signed on to help and, in handwriting aside each name, where best to reach them. Among those named are Walter Lippmann, Lincoln Steffens, William Allen White, and Winston Churchill, along with others just as well known in their day, representatives of so many of the major mainstream magazines and newspapers.

Lippmann, in these years, was the editor of the New Republic. For the magazine’s Oct. 7, 1916, issue, he managed what appears to be some deft double-servicing in support of both suffrage and President Woodrow Wilson’s re-election bid. He published “As One Woman Sees the Issues,” an essay by the physician, Alice Hamilton, the head of the Illinois State Commission on Occupational Diseases. Illinois had granted the women of its state the vote in 1913 and Hamilton’s piece responds to a request from the magazine to give her impressions of “how the newly enfranchised women voters are facing the perplexities of their first practical decision between presidential candidates.” She surveyed the positions of Wilson and his Republican challenger, Charles Evans Hughes, on the big questions of the day, from the war raging in Europe, to US “preparedness” for it, to relations with Mexico.

Hamilton also acknowledged Wilson’s foot-dragging on women’s suffrage over against Hughes’ announced support for the measure, something she was especially sensitive to as a newly minted voter, mindful of the women of so many other states who were still being denied the privilege. But just as quickly, she qualified that reservation. The other, more pressing issues facing the nation needed to take precedence, she wrote, and so Wilson would still get her support. In the Papers of Woodrow Wilson, dated 12 days before Hamilton’s piece was published, is an entry from Norman Hapgood, another Men’s League stalwart, passing word of the essay to the White House. Hapgood, who lost his editorship at Collier’s over his support for Wilson (Robert Joseph Collier, the magazine publisher, was a close friend of Wilson’s Bull Moose Party challenger, Theodore Roosevelt), succeeded Harvey at Harper’s Weekly in 1913.

On Aug. 4, 1920, in a special supplement to the New Republic, Lippmann and Charles Merz would publish “A Test of the News” with its groundbreaking analysis of bias in US news coverage of the 1919 Russian Revolution. The two journalists appealed to their colleagues to adopt the “scientific spirit” and to aspire to “a common intellectual method and a common area of valid fact,” as Bill Kovach and Tom Rosenstiel explain in the Elements of Journalism. The point, often lost, is not that journalists themselves needed to be free of bias—that would be nigh on impossible, anyway—but that the methods journalists deploy in their work should strive to meet a consistent, more scientifically oriented standard. In time, the codes of ethics of high-end newspapers would discourage or forbid even the appearance of bias from their reporters—for example, petition-signing, or contributions to political candidates, controversial causes, or even causes one might cover.

True, although the notion of an ethical framework for journalists was already in the zeitgeist in the 1910s, the great social science awakening in the field would take another several years to crystallize. Nonetheless, thinking logically, couldn't all the public display and advocacy have undermined the credibility of what they published in support of it? Or, more generally of the publications they edited? Would this not have been especially true for such advocacy of a cause as hated as women's suffrage? Or at least at least scoffed at for more than half a century as women’s suffrage, opposed by as many women as men?

In the final, crucial decade of the campaign, both at the state and the federal level, there is no doubt that the willingness of influential writers, editors, and publishers to declare themselves as suffragists, to risk their personal reputations, and to use their greased access to the widest avenues of popular persuasion, was a critical factor in the victory soon to come.

These men of the press did not stay out of the fray. They stood up, spoke up, and acted up. They took sides to help right a wrong. They were prescient about the course history was poised to take, indeed, needed to take, and they helped history to take it.

Brooke Kroeger is a professor of journalism at New York University. Her latest book, The Suffragents, chronicles the prominent, influential men whose support helped women get the vote.