“Why Are We a Nation of Poor People?” Social Security and Progressive Populism in Wartime New York

By Jennifer Young

“Two-thirds of the families in this nation live at a level which is below that accepted as a minimum standard for health and decency…and the democracy and general welfare of the nation is critically menaced,” thundered one of the United States’ longest-serving independent congressman in the House of Representatives, introducing a bill promising sweeping changes to the national social security program.[1] Today, these words conjure up the image of presidential candidate Bernie Sanders. Sanders has put democratic socialism into the news recently, criticizing the “billionaire class” and defending the rights of workers against corporate interests. While recent media coverage has focused on Sanders’ Jewish background and his relationship to Jewish socialist movements such as the Jewish Labor Bund, historians and longtime residents of New York City might recall that, until Bernie’s political rise, the scrappy populist underdog in Congress everyone recognized was Congressman Vito Marcantonio, who represented New York’s 18th District (East Harlem) as an independent from 1938-1951. Marcantonio, a first-generation Italian American, lived his entire life within several blocks of his birthplace in East Harlem, while building a significant coalition movement encompassing Italians, Puerto Ricans, Blacks, and Jews.

Indeed, although the comparison between Sanders and Marcantonio has been noted in articles in Jacobin Magazine, New Politics, and even by Sanders himself,the strong resonance between the two men has been generally overlooked during the current election campaign.[2] Yet the deeper historical roots of Sanders’ brand of progressive populism is worth exploring. Sanders is the heir to an American political tradition dating back to the Great Depression. His antecedent Marcantonio fashioned a political style that remains relevant to current discussions of the place and potential for democratic socialism in American life today.

Marcantonio was first elected to the US House of Representatives in 1934, as a Republican under the closetutelage of Mayor LaGuardia. He was defeated by the pro-Roosevelt upswing in 1936, but rebounded in 1938 after running on the American Labor Party (ALP) ticket. The ALP was founded in 1936 by a number of New York’s needle trade leaders, including International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union president, David Dubinsky. ALP voters, a majority of whom were socialist Jewish garment industry workers, could vote a socialist ticket while also selecting FDR for president. By 1946, the ALP was the largest party in East Harlem, with a growing Black constituency.[3] Although the ALP functioned primarily to funnel socialists’ votesto the Democratic Party, the party also channeled votes for progressive Republicans such as LaGuardia, even though Marcantonio led the pro-Communist faction within the ALP, which took control of the party by the early 1940s.[4]

East Harlem, a historically Italian neighborhood, became the center of postwar Puerto Rican migration, and alsoserved as a significant center for Black urban migration. By the mid-1950s, it was one of the world’s most densely populated areas, as Puerto Ricans and African Americans crowded into tenement apartments or newly constructed housing projects. Housing and employment were the most important political issues in the district. Marcantonio gained popularity with his constituents by speaking fluent Spanish, as well as Italian, and by supporting the Puerto Rican independence movement; he also addressed local issues such slum clearances and housing code violations.

Marcantonio introduced a diverse portfolio of progressive bills and measures throughout his years in office. One bill he championedhas particular resonance with growing grassroots and leftwing movements today: the campaign to introduce a guaranteed minimum annual income. Last month, the province of Ontario announced a pilot project to design a basic income program that would replace multiple government benefit programs with one check for all.[5] With similar programs in the works in Finland, the Netherlands, and possibly Switzerland, the idea is gathering momentum.[6] Even conservatives like the idea –- it was proposed by Richard Nixon as an alternative to the government’s Aid to Families with Dependent Children program, in August 1969.[7]

In the years just prior to America’s entry into World War II, coalitions of leftwing groups loosely associated as “Popular Front” political coalitions worked both inside and outside of electoral politics to extend and intensify President Roosevelt’s New Deal social welfare programs. On May 8, 1941, Marcantonio introduced H.R. 4688, the Guaranteed Minimum Income and Social Security Act, a bill to “guarantee minimum income and social security.” The aim of the bill was to “provide a nation-wide system of social security and a guaranteed minimum family income,” athough its practical breakdown of the beneficial economics of this proposal was somewhat overshadowed by the bill’s perhaps grandiose secondary proposals, “to extend opportunity for gainful and useful employment to all willing workers; to establish a program of Federal public works and services; to expand the domestic market for agricultural and industrial products; to assure a more equitable distribution of national income, [and] to establish a basic American standard of living.”[8]

On the surface, the bill’s aim was straightforward: to call upon Congress to authorize payments from the Federal Treasury to the Social Security Board, and through the Board to all American citizens, to provide a guaranteed minimum income of $2,500 to every head of a family with over three members (over $40,000 in contemporary currency). A family of three would receive $1,200 annually, in increments of $100 per month. A family of two would receive $1,080, or $90 per month, and a single individual over 18 would receive $720 per year.[9]This money would be available to any person or head of family whose net earnings for the last most recent twelve-month period did not total the maximum allowed under the proposed annual allotment. To put this in perspective, according to a 1940 Bureau of Labor Statistics report, eight million American family incomes averaged only $758 per year, with many people spending only $1 per week onfood, medicine, and housing food and personal necessities.[10]

The bill was referred to the Committee on Ways and Means and was promptly abandoned. It received no support from either major party, and, after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union just a few weeks after the bill’s introduction, Congress’ attention, and Marcantonio’s energies, turned towards the war. Yet it’s important to note that the bill was not an isolated attempt at making radical changes to FDR’s social welfare plan; in fact, it was the culmination of a long grassroots campaign for social welfare reform spearheaded by a pro-Communist, interracial labor fraternal organization, the International Workers Order (IWO), in which Marcantonio held the role of Vice-President.

The IWO was founded as a pro-Soviet breakaway group from the the Workmen’s Circle, a Jewish socialist fraternal order, in 1930. While its initial membership was comprised entirely of leftwing, working class Jews, IWO leaders quickly built relationships with other working-class ethnic fraternal movements, adding Hungarian, Russian, and Ukrainian fraternal groups under its umbrella. The IWO offered low-cost health and life insurance, filling a necessary gap which, IWO leaders argued, the government ought to fill. By 1940, the IWO encompassed 15 national group sections and included 155,000 members nationally. As a coalition builder himself, Marcantonio’s relationship to the IWO proved productive. Furthermore, upper Manhattan was a primary locus for IWO lodges: there was an Italian Lodge in the Italian section of Harlem, and Czech, Hungarian, and Irish IWO lodges in Yorkville;[11] Jesus Colon, leader of the IWO’s Hispanic section, did significant organizing work in East Harlem’s Puerto Rican area (El Barrio), while Louise Thompson, also a vice-president of the IWO and its senior ranking Black official, recruited Black members into central Harlem’s interracial Solidarity Lodge.

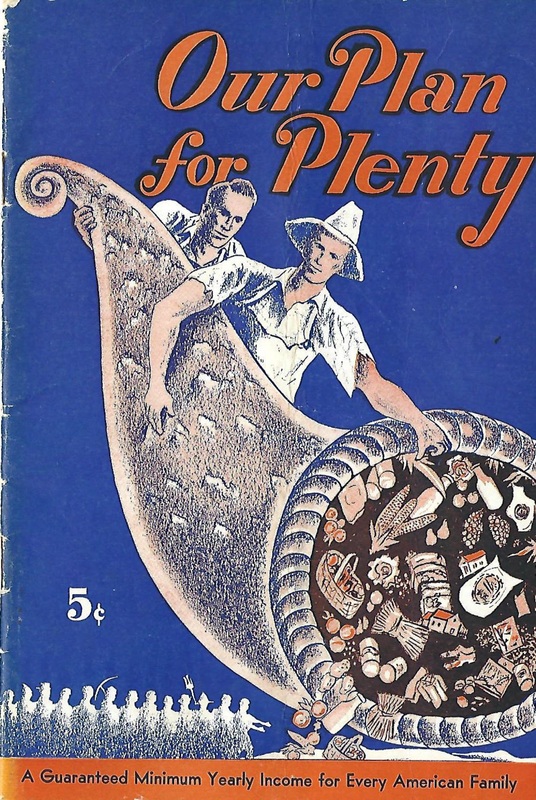

In 1940, the IWO launched a national campaign to promote their plan for a guaranteed annual minimum income, entitled “Our Plan for Plenty.” In conjunction with a national speaking tour led by former U.S. representative Jerry J. O’Connell, a progressive Democrat from Montana, the IWO sponsored 15-minute local radio broadcasts in major membership areas across the country.[12] The IWO’s goal was to push the government towards a much broader social safety net than that which President Roosevelt had introduced. The IWO’s General Secretary, German-born Max Bedacht declared that,since the “threat of hunger” [was] a“perpetual nightmare” for many Americans, the “Plan for Plenty” could provide an alternative, a “concrete reality” that would fundamentally change Americans’ relationship to scarcity, as well as profoundly altering the relationship between Americans and their government. As Bedacht argued, “the fraternal benefits of our order are emergency measures serving the improvement of social security for our members. Therefore working for universal social insurance is obviously a basic duty of our Order.”[13] In 1940, the IWO supported the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, and thus IWO leaders did not support America’s entry into the war; they used every opportunity to criticize the government for military expenditures instead of funding public works. Bedacht believed that“the most important thing…for national defense, [is] conditions worth defending.” He called for a national movement to fight for the Plan, arguing that the American people could exert enough power on the “naturally resisting forces of economic royalism” to eventually become law.[14]

The IWO produced a colorful 32-page booklet, entitled “Our Plan for Plenty,”published in each of the 15 languages of the IWO’s national sections. The argument inside the booklet is laid out clearly, created to appeal to the IWO’s mass constituency, the majority of whom were foreign-born members of the working class still struggling with the long-lasting social and economic effects of the Depression:

Our country is the richest in the world. Yet it is a nation of poor people. Why should millions of able, willing workers be idle with so many necessary jobs to be done? Why should billions of dollars of wealth lie idle, robbing the people of purchasing power because it is not invested to provide work, to produce goods? Why should millions of families lead lives tortured by disease, illness and physical disabilities –- all preventable -- while the talents of thousands of doctors and public health men waste away in idleness?...Why must ‘one third…’ of us live in slums, hovels and rickety shanties that breed crime and stunted bodies and minds? Why must old folks suffer the misery of want and destitution after a lifetime of work and service to their country? Why are we a nation of poor people? The answer is simple –- unjust distribution of our national income. Because it places profits above the needs of the people, our present economic system breeds this unjust income distribution, and the misery and degradation that follows in its wake…[15]

While summarizing the economic goals of the plan, the booklet also addresses the arguments of potential critics who would contend that the United States’ imminent entry into the war was no time to focus on new social security legislation. The solution, according to the booklet, is to ignore the warmongers’ interests, since these were the very industralists who benefited from the “armaments boom” in World War I. Bringing true economic security to the country, the text concludes, would bring a degree of hope to Americans more than another war economy would.[16]

When Hitler invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, invalidating the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, the IWO’s leaders pledged full support for the war effort. They quickly scheduled an emergency meeting of the general executive for June 24, 1941, and agreed to unite the Order’s efforts to “defeat Fascism’s attack on the Soviet Union.” Vice-President John Middleton stated that the triumph of fascist forces in Europe would strengthen internal fascist tendencies within the United States, giving rise to the crisis of permanent economic insecurity and political instability. The IWO must defend American interests abroad, he argued, in order to protect American interests at home.[17] While IWO leaders later worried that they had abandoned their fight for social security as a martyr to their wartime anti-fascist campaign,[18] the IWO did launch one major social security campaign during wartime: In 1943, the IWO backed the Wagner-Murray-Dingell compulsory national healthcare insurance bill, a bill which would be revised and re-introduced in 1945, 1947, and 1948-49 before being permanently shelved.

New York remained a strong social democratic enclave throughout the postwar era, but the emerging domestic Cold War changed the national political landscape. In the 1950 election, Marcantonio lost his congressional seat after casting the only vote opposing the Korean War. In 1953, New York State’s Insurance Department shut down the IWO, its insurance charter revoked on the grounds that it was operating as a Communist organization. Marcantonio died suddenly of a heart attack in August 1954, within steps of City Hall. A collection of his speeches, entitled “I Vote My Conscience,” appeared in 1956, preserving his words and deeds for future generations to revive and return to the political mainstream.

Jennifer Young is a Ph.D. Candidate in History at New York University, and currently serves as Digital Learning Curator for the YIVO Institute. Her dissertation focuses on the International Workers Order and interracial politics within the Communist movement in New York.

[1] Vito Marcantonio, Guaranteed Minimum Income and Social Security Act, H.R. 4688, 77th Cong. (1941).

[2] See, for example, Steve Early, “Labor For Bernie,” in Jacobin Magazine, May 26, 2015, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2015/05/bernie-sanders-president-primary-hillary/; David McReynolds, “Bernie Sanders as I’ve Known Him,” in New Politics, June 4, 2015, http://newpol.org/content/bernie-sanders-ive-known-him; and Bernie Sanders, July 1988, as quoted in “Bernie Sanders had ‘no intention of becoming a Democrat,’ The Telegraph [UK], Feb. 19, 2016, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/us-politics/12163433/Bernie-Sanders-had-no-intention-of-becoming-a-Democrat.html .

[3] Gerald Meyer, Vito Marcantonio: Radical Politician, State University of New York Press, New York, 1989, p. 26.

[4] Meyer, Vito Marcantonio, p.27.

[5] Erin Fotheringham, “The Hidden Highlight of Ontario’s 2016 Budget,” in The Huffington Post [Canada], March 2, 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.ca/ontario-association-of-food-banks/ontarios-2016-budget_b_9365652.html .

[6] Emma Henderson, “Switzerland will be the first country in the world to vote on having a national wage of £1,700 a month,” in Independent [UK], Jan. 30, 2016, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/switzerland-will-be-the-first-country-in-the-world-to-vote-on-having-a-national-wage-of-1700-a-month-a6843666.html .

[7] Mike Alberti and Kevin C. Brown, “Guaranteed income’s moment in the sun,” April 24, 2013, http://www.remappingdebate.org/article/guaranteed-income%E2%80%99s-moment-sun .

[8] H.R. 4688, p.1.

[9] H.R. 4688, p.8.

[10] “Our Plan for Plenty,” published by the International Workers Order, New York, 1940, p.2.

[11] Meyer, Vito Marcantonio, p.69.

[12] International Workers Order Records, 1927-1956. 5276. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library. Fifth Convention Minutes, Box 3, Folder 2.

[13] International Workers Order Records, 1927-1956. 5276. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library. Box 3, Folder 15,Max Bedacht, “Our Plan for Plenty” manuscript, p.1.

[14] International Workers Order Records,Box 3, Folder 15, Max Bedacht, “Our Plan for Plenty” manuscript, p.8.

[15] “Our Plan for Plenty” booklet,published by the International Workers Order, New York, 1940, p.1.

[16] “Our Plan for Plenty” booklet, published by the International Workers Order, New York, 1940, p.8.

[17] International Workers Order Records, 1927-1956. 5276. Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation and Archives, Cornell University Library. Box 4, Folder 1, Speech by John Middleton delivered at IWO staff meeting, Tuesday, June 24, 1941.

[18] International Workers Order Records, Box 3, Folder 13, Max Bedacht, “Our Anti-Fascist Task of Today,” September 1945.