A Comprehensive Subway

By Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin

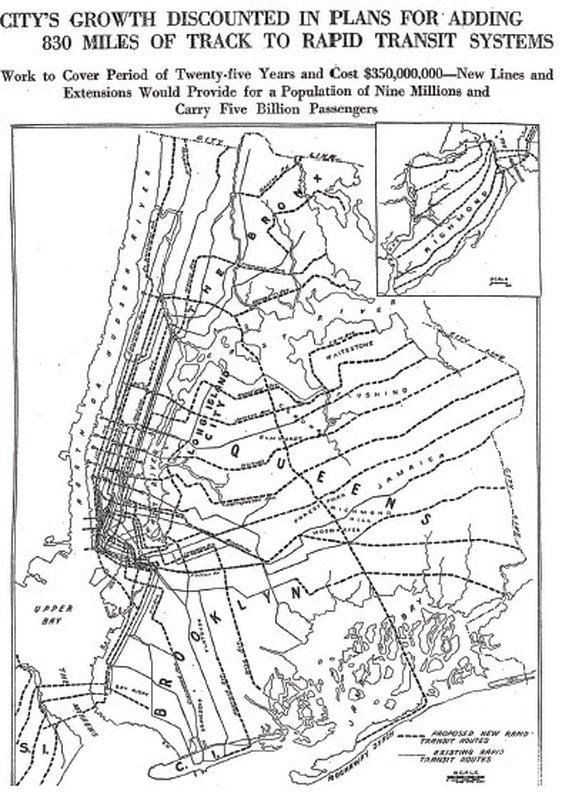

Photo in "The New York Rapid Transit Railway Extensions," Engineering News, 1914

The name Daniel Lawrence Turner means nothing to New Yorkers. But save for poor timing, he was almost the mastermind behind the most far-reaching subway plan ever proposed for New York City.

Turner, chief engineer of the city’s Transit Construction Commission, was concerned by the alarming increase in traffic on the city’s street railways and trolleys, which, according to his estimates, had “nearly doubled every ten years.” Realizing the “necessity of an orderly development of rapid transit lines in all sections of the City,” and wanting to get ahead of development rather than follow it, in 1920 he submitted the “Report By The Chief Engineer Submitting For Consideration a Comprehensive Rapid Transit Plan Covering all Boroughs of the City of New York.”

This is the third in a series of posts drawn from the authors'recent work

Never Built New York, published courtesy of Metropolis Books.

The 19-page document called for a municipally controlled (at this time, all lines were privately run) 25-year building program estimated to cost from $175 to $350 million. Among Turner’s aims: five new trunk subway lines and nine new crosstown lines in Manhattan, and more than 40 new lines or extensions in the outer boroughs. Almost all would, at some point, traverse the city center, dozens would cross the river, and three would make their way from Brooklyn to Staten Island via tunnel. The 830-plus miles of new routes (in addition to the city’s existing 600 miles) would more than double the number of miles in today’s subway system.

“In order to keep pace with the enormous traffic growth, the City must build more transit facilities––then more again––and still more again––and must keep on doing this continually,” wrote Turner, who later in his career proposed schemes like the creation of underground sidewalks and moving walkways throughout the city to help ease congestion.

After the 1920 state elections, new governor Nathan C. Miller established the New York State Transit Commission, which, he proclaimed, would be independent of the influence of Tammany Hall, among other things. The bitterly disputed consolidation of power, which put many city transit administrators out of work, held up the subway plans and many other initiatives. Ultimately, city and state legislators fought over control of a centralized transit system for the next several years. Other comprehensive plans were proposed, none of them successfully, and nothing as ambitious ever came to fruition.

Sam Lubell is a Staff Writer at Wired and a Contributing Editor at the Architect’s Newspaper. He has written seven books about architecture, published widely, and curated Never Built Los Angeles and Shelter: Rethinking How We Live in Los Angeles at the A+D Architecture and Design Museum. Greg Goldin was the architecture critic at Los Angeles Magazine from 1999 to 2011, and co-curator, and co-author, of Never Built Los Angeles. His writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Times, Architectural Record, The Architect’s Newspaper, and Zocalo, among many others.