How Can You Live in the City? Martha Rosler's "If You Can't Afford to Live Here Mo-o-ove!"

By Pollyanna Rhee

“Come on in, we’re home!” The welcoming red sign on the door stood in stark contrast with the similarly minimalist galleries on the block. But this wasn’t your typical gallery, at least not between June 7 and July 9, when the Mitchell-Innes and Nash Gallery on West 26th Street in Chelsea became the “Temporary Office of Urban Disturbances” for If You Can’t Afford to Live Here Mo-o-ve! a new iteration of Martha Rosler’s decades-long exploration of housing, homelessness, and urban conditions in New York City and beyond.

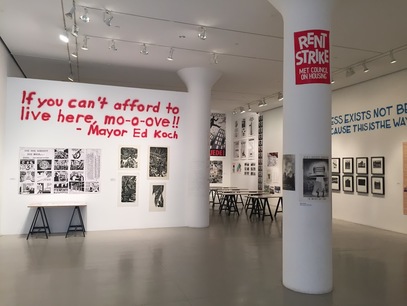

The warm welcome belied the content inside. In the foyer, hand-drawn signs and t-shirts from housing protests announced a rent strike and demanded “Housing Not Shelters,” while “Occupy” barricade tape lined the reception desk. The show’s credits and participants, usually affixed on gallery walls in vinyl letters, were printed on paper and posted with their ends curling under. Across the gallery, a poster reading “War Against the Poor” hung underneath large spray-painted letters of Ed Koch’s famous directive, “If you can’t afford to live here mo-o-ve!” Through a variety of artistic, archival, and curatorial strategies honed since Koch’s mayoralty, Rosler’s career demonstrates a willingness to provoke viewers to consider widening urban inequality and the role of art and its institutions in both perpetuating and resisting it.

Twenty-seven years ago, a similar welcome sign was posted on the door to the Dia Art Foundation’s space at 77 Wooster Street in Soho for Rosler’s If You Lived Here …. a series of three exhibitions focused on putting into relief the conditions that produced homelessness and inadequate housing. The first, “Home Front,” was conceived as “a set of representations of contested neighborhoods.” Rosler established an ambience distinct from traditional galleries, mixing graphs and statistics with ads for luxury real estate in Manhattan along with a prominent place for Koch’s statement.[1]

The second, “Homeless: The Street and Other Venues” concentrated on homelessness as an acceptable aspect of capitalist urban conditions, an idea exemplified by scholar Peter Marcuse’s statement that homelessness exists “not because the system is not working but because this is the way it works.” Finally “City: Visions and Revisions” presented projects that imagined or worked towards solutions to urban problems.

Now, in Chelsea, If You Can’t Afford to Live Here Mo-o-ove! combined work from those shows with more recent projects. Intertwined with housing inequality was another long-standing interest of Rosler’s, the nature of art galleries as institutions. Rather than hosting a traditional gallery show with works by artists who use housing and homelessness as central topics, Rosler’s curation combined art in a variety of media with research projects, documentary films, ephemera, policy proposals, and newspaper clippings. Even her renaming of Mitchell-Innes and Nash’s suggested that Rosler endeavors to shift expectations of what galleries are supposed to do, and to underscore how they are also part of the cities they inhabit (whether they like it or not). After If You Lived Here …., Rosler observed that many commentators noted the “transgressive character” of the exhibitions and “some seemed to miss the pristine quality of the modernist space, feeling intimidated by the volume of work and the reading room.” Who, exactly, experienced these feelings of intimidation? For Rosler, it was those art-world professionals who approached the project as an “outright rejection of art.”[2]

Challenging the social dynamics of gallery spaces by presenting this material emphasizes Rosler’s belief that “the city is art’s habitat.”[3] Here housing is more than just shelter; it is one of the numerous resources and gathering spaces that shape urban experiences and expectations, a vital site of community building. It makes sense that many of the works in If You Can’t Afford to Live Here Mo-o-ove! centered on the social infrastructure of a city, which includes, but is not limited to, housing. A toy bulldozer pushing a loaf of bread displayed on one wall represented the work of 2Up 2Down, a project started for the 2012 Liverpool Biennial with artist Jeanne van Heeswijk and residents of Liverpool’s Anfield neighborhood.[4] After the loss of Mitchell’s, the neighborhood’s century-old, family-owned bakery, in 2010 van Heeswijk worked with local residents to start Homebaked, a new community-owned bakery at the same site. The ideas that sparked the bakery have expanded with the Homebaked Community Land Trust that helps residences to collectively buy, develop, and manage land and buildings in the neighborhood.

In a similar vein, the Brooklyn Laundry Social Club formed in 2012 as a “mobile community center” uses laundromats as social spaces to discuss and imagine alternatives to gentrification especially as rising rents and laundry delivery services have drastically reduced the number of laundromats in the neighborhood. A hand-labeled map of Bedford-Stuyvesant on display included a legend for residents, with markers showing where “sophisticated people meet,” and where “to find a copy of C.L.R. James’ The Black Jacobins,” and "your favorite bodega.” The map provided information about the neighborhood at a community-oriented scale, underscoring the spatial and social networks that residents use to navigate their neighborhood. Like 2Up 2Down, the BLSC proposed converting some mom-and-pop laundromats to co-ops, in which customers, workers, and members of the community would have a stake not just in a business, but a shared project.

Other works documented the breakdown of community institutions and their aftereffects. Photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier’s Braddock Hospital Photo Campaign (2011) about the closing of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania featured Levi’s clothing advertisements that romanticized the city’s deindustrialization as an ideal location for new (affluent and white) “pioneers” to inhabit. Frazier repurposed these ads with her own commentary underscoring the historical erasures of the city’s steelworkers and the toxic environmental legacy that industry left behind. One advertisement announced that “Everybody’s Work is Equally Important” with the Levi’s logo and “Go Forth” printed underneath. A handwritten rejoinder asked why, if that’s the case, local residents and small businesses did not receive a share of profits from materials salvaged and sold from the Braddock Hospital demolition process. In another, Frazier placed an asterisk on a listing for artists studios in Braddock noting that the building contains asbestos and black mold.

Rosler’s documentary approach sometimes omits commentary. Clippings posted on a pillar in the middle of the gallery included a page from the New York Times in December 1988 with a headline about closing Washington, D.C. Metro stations to the homeless and included a quote from Beverly Silverberg, spokesperson for the Metro, “We feel compassion for the homeless but it is not our responsibility.” Printed above the article was a photograph of the Duke and Duchess of York in Greenwich, Connecticut at a benefit for the American Fellows of the Tate Gallery. This clipping shared space on the pillar with a photo from the same year of Donald Trump stroking a model of a proposal for Trump City on Manhattan’s west side.

While Rosler’s show focused on housing and local businesses in working-class communities, the forces of economic displacement don’t spare art galleries, either. Next to the Temporary Office of Urban Disturbances’ front door a map indicated the locations of art galleries in New York City. SoHo, the center of gallery life before Chelsea, now contains relatively few, pushed out by rising rents. Today, Chelsea is less the bastion of galleries it once was, the neighborhood’s transformation instigated in part by the galleries and the High Line that sits less than a block away from this show’s location.[8] Across the street, a gallery-themed Starbucks has replaced a gallery, around the corner, several 25th street art spaces now serve as a Tesla showroom, and one-bedroom apartments next to the High Line rent out for almost $5000 a month. Today, galleries have decamped to the Lower East Side or parts of north Brooklyn, but if the past is any indication, neither they nor their working-class neighbors will be there for long.

During If You Lived Here …. people in the art world asked Rosler why she would have that show in SoHo. “There could be no answer for those who feel that Soho is a true enclave, the Vatican of art, physically located in, but otherwise exempt from, the rules of New York.,” she noted soon after.[7] There is much to say about the fate of SoHo, but perhaps one appropriate answer would be merely to note that the gallery on 77 Wooster Street that presented If You Lived Here …. in 1989 is now the DwellStudio flagship store. Rather than flouting the rules of New York, If You Can’t Afford to Live Here Mo-o-ve! demonstrated some of the possibilities for an artistic and curatorial practice engaged with urban transformations happening just outside the gallery walls.

Pollyanna Rhee is a PhD Candidate in History and Theory of Architecture at Columbia University.

[1] Martha Rosler, “Fragments of a Metropolitan Viewpoint,” in Brian Wallis, ed. If You Lived Here: The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism, A Project by Martha Rosler (Seattle: Bay Press, 1991), 35-6.

[2] Id., 40.

[3] Id., 32.

[4] 2up2down.org.uk and homebaked.org.uk.

[5] The contents of Rosler’s library are at www.e-flux.com/projects/library/.

[6] Mireya Navarro, "In Chelsea, a Great Wealth Divide," New York Times, October 23, 2015.

[7] Rosler, “Fragments” (1991), 40.