"All the Single Ladies": Women-Only Buildings in Early 20th c. NYC

By Nina E. Harkrader

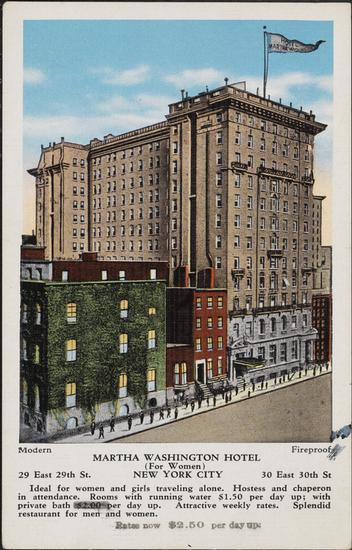

Hotel Martha Washington Postcard, 1920. Museum of the City of New York.

The growth of manufacturing and industry in Northeastern cities during the early to mid-19th century increased demand for female labor in the United States. As a result, the number of single working women living in urban areas grew significantly. These newly arrived women workers were expected to find their own lodging, but there were no precedents for housing single women in cities. On top of that, the much lower wages paid to female workers greatly limited their housing choices, and many ended up living in squalid situations: shared bedrooms in tenement buildings or hired rooms in boarding houses with male lodgers. For women workers in cities, two problems emerged: a literal housing crisis, but a figurative one as well, as this was a period when female chastity, innocence, and domesticity were celebrated and expected of women, who would perform the role of “the angel in the house” and rarely, if ever, appear unaccompanied in public.

Upper and middle-class New Yorkers quickly grew alarmed by the number of young, single women living in cities apart from their families—alone, unprotected, and unsupervised. The practical question of finding decent accommodation for single working women thus also became a moral one of preserving the purity, dignity, and femininity of future wives and mothers. These tensions between the increasing numbers of working women and societal expectations would continue for decades. As a result, during the period from about 1860 to 1930, urban housing for single working women—its location, design, and even its furnishings—became central to the struggle for women to be accepted as independent citizens.

Early Housing: “Moral Homes”

New York City was among the first places to address the challenge of providing appropriate housing for young, working women. Beginning in the 1860s, a group of wealthy and charitable Christian women, the Ladies Christian Union (LCU), decided to provide what they termed “homes” at a low cost for factory workers, seamstresses, shop girls, and the like. The choice of the term was conscious: these early homes were former middle-class houses refitted with genteel furnishings, while the interior spatial organization of parlour, dining room, kitchen, and upstairs bedrooms was maintained. Nor was it a coincidence that the house matron was referred to as the “mother” who looked after her “daughters.” Admission was restricted to those young women who were self-supporting and considered to be of good moral character. In an LCU Home, material comforts and shelter were offered in exchange for following strict rules designed not only to encourage but to enforce, good behaviour.

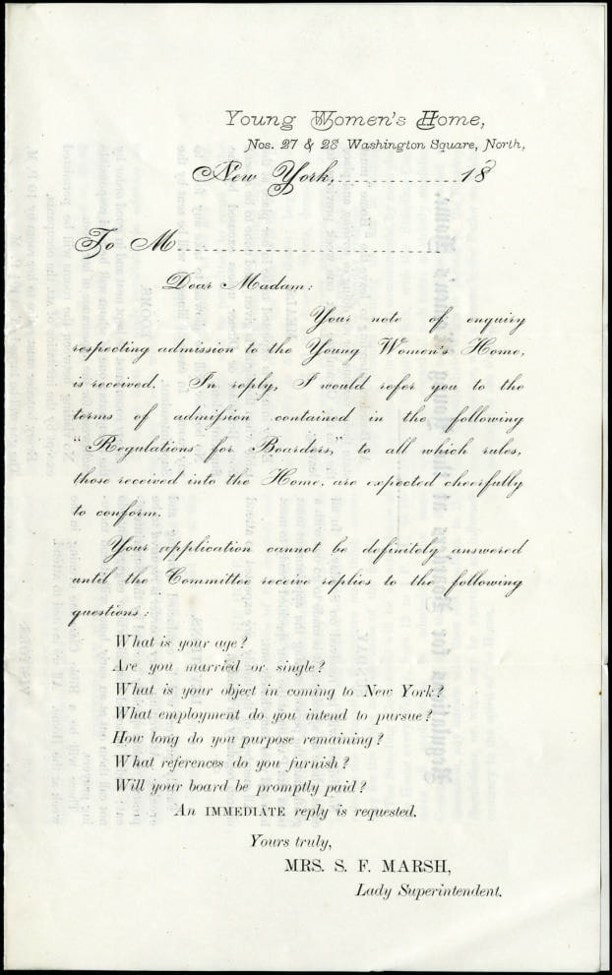

Admission Form and Regulations for an LCU Young Women's Home, c. 1870.

YWCA Margaret Louisa Home, 1907. Byron Company. Museum of the City of New York.

An 1870 copy of the rules for an LCU Home informed prospective tenants that “those who avail themselves of the comfort of the Home, must be young, unmarried and furnish satisfactory testimonials of character, also in what employment they were engaged, or intended to pursue.” If a young woman was accepted, she had to keep her room “neat and clean,” attend morning prayers, be present at breakfast and dinner, entertain any guests in the parlour, and adhere to a ten o’clock bedtime (at which point the gaslight in the Home was extinguished.) She could be expelled for breaking any of these rules, or for “exerting an influence contrary to the spirit of the Home.”

Thus, the LCU Homes were consciously designed, in their furnishings, organization, and rule,s to teach young working women, who came from the lower classes, how to behave like good, middle-class girls; the assumption being that they would, after being part of the LCU “family,” become wives and mothers.[1] Whether or not this strategy was successful might be contested, but nearly fifty years later, the LCU was still operating five successful homes. More importantly, their idea of a Moral or Benevolent Home for well-behaved working girls became the housing model for other organizations concerned with the plight of single working women in New York City, and this model would continue to exert influence into early 20th century.[2]

Purpose-Built Accommodation: The YWCA

By the late 19th century, not only were unmarried working-class women toiling in factories, mills, shops, and various trades, but middle-class women were employed in new white-collar jobs as clerks, secretaries, stenographers, journalists, and telephone operators. An 1879 report of the Association for Inquiry into the Condition of Professional and Business Women estimated that there were about 50,000 women pursuing “professional, literary, and artistic pursuits” in and within 50 miles of New York, while there was only accommodation for 500.[3] The need for housing was so great that the LCU and similar organizations were turning away three applicants for every one they could house.

The Young Women’s Christian Association of New York City constructed the first new building designed specifically to house single working women.[4] Completed in 1891 at 14-16 Sixteenth Street, the six-story Margaret Louisa Home was described as “a temporary home for the Protestant self-supporting woman who is a stranger within the gates of Gotham.” The requirements for acceptance to the house show the continued emphasis on moral character: “those desiring admission [must] provide a name, occupation, church denomination, and the name and address of a reliable person…” Thirty years on, the house rules were as strict as those in the earlier “moral homes.” Rent was payable in advance, no cooking or washing was allowed on the premises, electricity was “extinguished at 11 o’clock,” and “the house is closed at 11 p.m.; those liable to be detained later must report at the Superintendent’s office in advance.”[5]

The Margaret Louisa was a new type of building, much larger than any earlier home (it could accommodate up to 110 women). Still, it was consciously designed, under the leadership of the all-female association board, to “have that indescribable, indispensable something—sympathetic home influence.” Contemporary descriptions of the public spaces note the walls were “painted in warm, soft colors which add greatly to the charm of the finish,” while “the parlors are tastefully furnished, with engravings, a piano… reading lamps… all of which give a peculiar home-like air to these surroundings.”[6]

In contrast, the bedrooms at the Margaret Louisa were quite small and furnished plainly. Photos from about 1907 show a dormitory bedroom crowded with three iron bedsteads, small wash basins, a bureau, and a shelf. While the single-bedroom photo has similar furnishings, it appears staged as an attractive, feminine, middle-class space, a sort of “aspirational” bedroom with a vase of flowers, pictures on the bureau, and personal items pinned up behind a shelf, which also has assorted knick-knacks.[7]

More occupants meant a lower cost per boarder, which might explain the small size of the bedrooms and their spartan furniture. However, it is interesting to contrast the austere nature of the small, almost institutional bedrooms, with the attractively decorated public rooms—rooms where genteel practices like reading or playing the piano were encouraged. Even though the residents, for the most part, were middle-class, professional women—teachers, artists, and journalists—in form, furnishings, and rules, The Margaret Louisa continued the traditions of the “Moral Home.”[8]

Hotels for Women?

The benevolent home was not the only model proposed to house single, working women in New York City, however. In 1869, mercantile magnate Alexander T. Stewart—whose stores employed many young women as “shop girls”—proposed the Hotel for Working Women, the first of its kind. At the time,single women were never admitted to hotels; to be a guest, a woman had to be accompanied by a husband, or check-in as part of a family with a male head of household. Stewart stated his hotel would be for “industrious young women...to foster individuality and self-dependence... in which lodging, food, and warmth, with other essentials, may be furnished at the lowest possible rates.”[9]

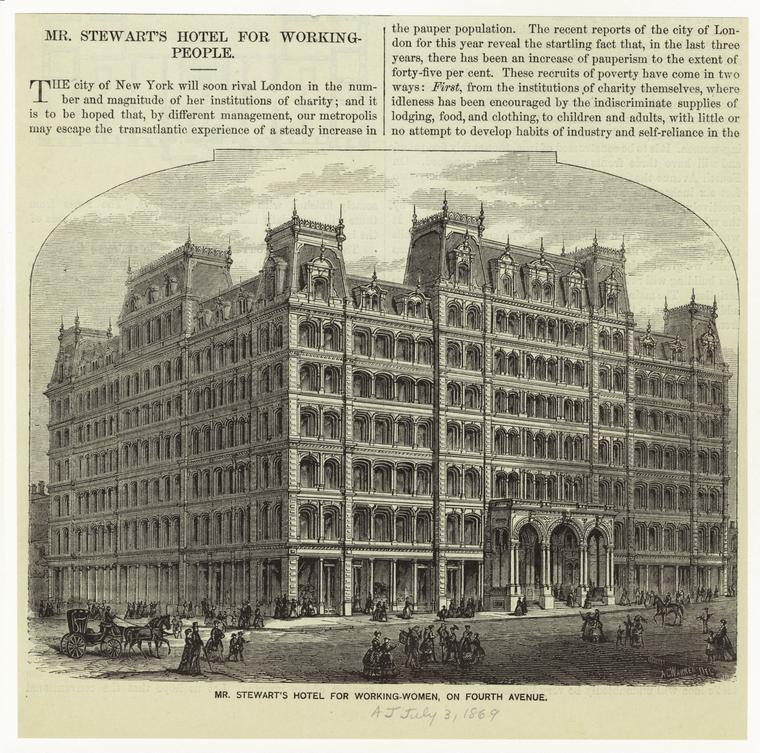

Mr. Stewart's Hotel for Working-Women, on 4th Avenue. New York Public Library.

Located on Park Avenue between 32nd and 33rd Streets, the Hotel for Working Women stood in startling contrast to the small size and austerity of the moral homes: it was a grand structure, seven stories tall, and built of iron with a mansard roof, interior courtyard with flowers and a large fountain, and an elegant marble-columned lobby. Inside, it boasted five elevators, marble floors with carpets, more than 1,700 gaslights throughout the building, speaking tubes to communicate with the staff, and hot and cold running water throughout. The upper floors had single and double rooms, while the lower floors featured a dining-room, parlors for entertaining guests, reading rooms fully stocked with books and periodicals, and other amenities. At the time of its completion in 1878, press coverage of the hotel’s opening was extensive and largely laudatory. It was compared favorably to contemporary hotels, and on the opening day, the hotel manager reported 1,000 applications for rooms.[10] Sadly, this novel experiment was curtailed almost immediately: Stewart died before the Hotel’s completion, and within a year, it was sold and converted into The Park Avenue Hotel, a market rate hostelry that catered to a well-heeled and largely male clientele. This conversion was controversial. The executor of Stewart’s estate maintained that the hotel had never been fully occupied and thus was a financial failure. Women’s groups countered that the hotel had a long waiting list, and that the executor stood to profit personally from its conversion to a luxury hotel.[11]

Free from Paternalism: The Hotel Martha Washington

Perhaps because of the Stewart hotel’s apparent failure, it wasn’t until nearly thirty years later that a second women’s hotel was constructed in New York City: The Hotel Martha Washington. Designed by Robert Gibson and completed in 1903, the twelve-story Martha Washington was designed to house 400-500 “business women” and to provide specifically for this groups’ needs, at 30 East 30thStreet. From the start, the hotel was conceived as a profit-making venture, organized and executed by the Women’s Hotel Company (incorporated in 1897), and funded by investments from New Yorkers such as William Schermerhorn, John D. Rockefeller, Helen Gould, and Olivia Sage (the wife of Russell Sage and founder of the Russell Sage Foundation). In practice, women were responsible for the success of the project. By the time the hotel opened, much of the stock was owned by individual women backing the idea of a women’s hotel.[12]

Lobby of the Hotel Martha Washington, 1903. Byron Company. Museum of the City of New York.

An early promotional brochure describes the Martha Washington as a “world-famous and interesting hostelry... well appointed, thoroughly modern, strictly fireproof and equipped with every facility for the comfort of its guests.” These included a drug store, ladies tailor shop, millinery, manicurist, and newspaper stand. The staff was entirely female, down to the elevator operators. The brochure also highlights the role of women in planning the interior design of the hotel: “woman’s wit has been used to provide the little necessities and comforts so much appreciated by her…”

Promotional materials emphasized a unique aspect of the Martha Washington Hotel: not only was it was intended for professional women, but it was planned without “paternalism or philanthropic idea,” and had “no harassing restrictions… imposed on the hotel guests other than those prevailing in the best hotels.”[13] At the Martha Washington, female residents were afforded the same freedoms allowed their male counterparts. In contrast to the supervisory homes, this women’s hotel was explicitly linked with feminist ideals of independence, the ability to earn one’s own living, and the conscious presentation of white-collar working women as “business women.” It was a success: the building was fully occupied immediately with both permanent and transient guests and 200 more women on a waiting list. The hotel’s philosophy was met with approval by important feminist groups, including the Interurban Women’s Suffrage Council, who made the hotel their headquarters beginning in 1907.[14] The novel hotel caught the public’s eye, so much so that residents complained it had become a tourist attraction, complete with “lectures on megaphones” given atop tour buses.

The Trowmart Inn: Independence for Working-Class Women

While the Martha Washington established a model for housing business women, a 1907 housing exposé titled: “The Problem of Living for 97,000 Girls,” emphasized the “Absurd Restrictions and Poor Housing Conditions” working-class women continued to suffer. The article mentions one innovative solution, however: The Trowmart Inn. Completed in 1906, the Trowmart picked up on the ideas put into practice at the Martha Washington and, for the first time, provided accommodation for the working-class girl without the strict rules of a “Moral Home.” Like its inspiration, the Trowmart highlighted this fact in its promotional brochures. Compared to the Martha Washington, the inn’s interior spaces and furnishings were plain and even utilitarian, but the Trowmart provided similar amenities: a dining room and cafeteria, “beau parlors” (small parlors where the residents could entertain their gentlemen friends), a large parlor with a piano, a library, and doctor’s office. In addition, the Trowmart provided a sewing room, full laundry, and a drying room, essential spaces for the shop, millinery, and factory girls for whom the Inn was planned. Living expenses ran to $4.50 to $5 per week week, with breakfast and dinner included.

The Trowmart Inn was an immediate success: a 1908 newspaper article reported the hotel, which housed 250 women, had been full since its 1906 opening.[15] The Trowmart was the exception however.[16] The majority of women’s hotels constructed during the first few decades of the 20th century were for professional women.

Dining room of the Trowmart Inn, 1906. Byron Company. The Museum of the City of New York.

An early promotional brochure describes the Martha Washington as a “world-famous and interesting hostelry... well appointed, thoroughly modern, strictly fireproof and equipped with every facility for the comfort of its guests.” These included a drug store, ladies tailor shop, millinery, manicurist, and newspaper stand. The staff was entirely female, down to the elevator operators. The brochure also highlights the role of women in planning the interior design of the hotel: “woman’s wit has been used to provide the little necessities and comforts so much appreciated by her…”

Promotional materials emphasized a unique aspect of the Martha Washington Hotel: not only was it was intended for professional women, but it was planned without “paternalism or philanthropic idea,” and had “no harassing restrictions… imposed on the hotel guests other than those prevailing in the best hotels.”[13] At the Martha Washington, female residents were afforded the same freedoms allowed their male counterparts. In contrast to the supervisory homes, this women’s hotel was explicitly linked with feminist ideals of independence, the ability to earn one’s own living, and the conscious presentation of white-collar working women as “business women.” It was a success: the building was fully occupied immediately with both permanent and transient guests and 200 more women on a waiting list. The hotel’s philosophy was met with approval by important feminist groups, including the Interurban Women’s Suffrage Council, who made the hotel their headquarters beginning in 1907.[14] The novel hotel caught the public’s eye, so much so that residents complained it had become a tourist attraction, complete with “lectures on megaphones” given atop tour buses.

The Trowmart Inn: Independence for Working-Class Women

While the Martha Washington established a model for housing business women, a 1907 housing exposé titled: “The Problem of Living for 97,000 Girls,” emphasized the “Absurd Restrictions and Poor Housing Conditions” working-class women continued to suffer. The article mentions one innovative solution, however: The Trowmart Inn. Completed in 1906, the Trowmart picked up on the ideas put into practice at the Martha Washington and, for the first time, provided accommodation for the working-class girl without the strict rules of a “Moral Home.” Like its inspiration, the Trowmart highlighted this fact in its promotional brochures. Compared to the Martha Washington, the inn’s interior spaces and furnishings were plain and even utilitarian, but the Trowmart provided similar amenities: a dining room and cafeteria, “beau parlors” (small parlors where the residents could entertain their gentlemen friends), a large parlor with a piano, a library, and doctor’s office. In addition, the Trowmart provided a sewing room, full laundry, and a drying room, essential spaces for the shop, millinery, and factory girls for whom the Inn was planned. Living expenses ran to $4.50 to $5 per week week, with breakfast and dinner included.

The Trowmart Inn was an immediate success: a 1908 newspaper article reported the hotel, which housed 250 women, had been full since its 1906 opening.[15] The Trowmart was the exception however.[16] The majority of women’s hotels constructed during the first few decades of the 20th century were for professional women.

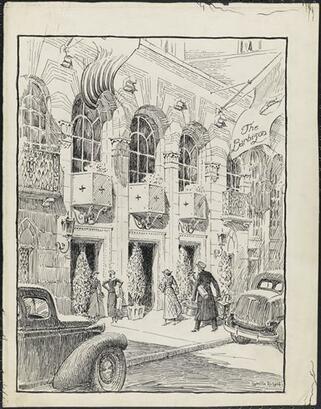

Greville Rickard, Barbizon Hotel, ca. 1930. Museum of the City of New York.

The most famous, and arguably the best example of the new, modern women’s hotel was The Barbizon Hotel for Women, built by Murgatroyd & Ogden and completed in 1928 at 63rd and Lexington. One of the Allerton Group partners, William Silk, was the developer, and the Barbizon resembled the Allerton in size and height, as well as in purpose: to provide amenities and entertainment in-house for single, professional women. Early newspaper coverage emphasized the Barbizon was designed for the “modern woman,” who was simultaneously depicted as “strong” and “dainty.” The Barbizon positioned itself as a hotel for women who wanted a career in the arts, taking its name from a school of French artists and advertising its proximity to cultural institutions.

The hotel included artists’ studios and music rooms, as well as a rich program of cultural events. There were facilities for dining, entertaining, reading, and exercising as well, including a gymnasium and a pool. As with the Martha Washington, there were also elegant shops on the ground floor.

Despite the modern and even luxurious amenities and public spaces, Barbizon bedrooms were small and fairly plain. As with earlier women’s hotels, the smaller rooms meant more occupants. A 1939 hotel brochure shows an image of a single bedroom with a somewhat glamorous inhabitant, while an amateur photo of a different single bedroom at the Barbizon reflects a starker reality: one window, a bureau, a small desk, and a day-bed.[18]

The End of Women-Only Lodging in New York City

The Stock Market Crash in late 1929 and the Great Depression that followed put an end to construction of women’s hotels in New York. When construction resumed after the Second World War, builders focused more on housing nuclear families, and less on single working women. While women-only residences remained popular well into the 1970s, a combination of social changes and economic factors meant that by the end of the 20th century, most of these remarkable buildings had closed or been converted. With the exception of the Webster Apartments (1923), nearing their one-hundredth anniversary, these pioneering women’s residences have largely disappeared.

Historian Nina E. Harkrader completed her doctorate in the History of Art and Architecture at the Institute of Fine Arts, NYU. Dr. Harkrader writes and lectures on a variety of nineteenth and early 20th century architectural and history topics. Her recent research interests include the relationships between social mores, working women, and buildings. Dr. Harkrader is currently writing a book about purpose-built housing for working women in New York City and London.

Notes

[1] NYT 2 June 1868: Sheltered for 140 during the year; most stay several months; 50 boarders in June, teachers, saleswomen, copyists, dressmakers, seamstresses. $3.50-$4 per week; single rooms, $5-6.

[2] Packard, Esther. “A Study of Living Conditions of Self-Supporting Women in New York City,” Privately published, Metropolitan Board of the YWCA, 1915.

[3] “An Association in Behalf of Women (sic),” New York Tribune, 26 June 1879. As the “Homes” were typically adapted from former houses, even the largest could only accommodate 45-50 women.

[4] The New York City YWCA was an offshoot of the Ladies Christian Union. Margaret Louisa Vanderbilt Shepard, 1845-1924, daughter of William Henry Vanderbilt and Maria Louise Kissam; paid for the building and its furnishings. Wikipedia cites Daphne Spain, How Women Saved the City as the source.

[5] MacLean, Annie M. “Homes for Working Women in Large Cities,” The Charities ReviewJul 1, 1899.

[6] Chicago Daily Tribune, 1894.

[7] Photos from the Byron Collection at the Museum of the City of New York.

[8] YWCA New York City Annual Report, 1902: 43. Despite the strict rules, supervision, and austere bedrooms, the Margaret Louisa was a success: in 1902 alone, the home admitted over 7,000 women, the majority of whom stayed between one and two weeks. In 1904, single rooms cost 50c a day, meals cost 20c for breakfast, luncheon or Sunday tea; dinner was 35c. The weekly expense for room and board amounted to $7.75, a figure far above the $3-5 dollars per week earned by many working women. Margaret Louisa Report, 1904.

[9] “Mr. Stewart’s Hotel for Working People.” Appleton’s Journal3 July 1869: 417-419.

[10] See The New York Times, 12 Nov 1877, 3-4 Apr 1878; “Women's Hotel at New York, Cambridge Independent Press, 11 May 1878.

[11] NYT, 2-9 Jun 1878.

[12] LPC Landmarks Report, “Martha Washington Hotel”, 19 June 2012.

[13] “The Hotel Martha Washington…”, Independent 25 June 1903, qtd in Landmarks Report, 2012: 7.

[14] The IWSC was an umbrella organization of twenty different New York City women’s suffrage groups headed by the redoubtable Mary Chapman Catt.

[15] “Helping Girls Would Pay: Hotel for a thousand would mean 4 per cent on investment,” NY Tribune8 Jul 1908.

[16] One other similar project, the Junior League Home Hotel, was completed in 1911 overlooking the East River.

[17] “A Business Women’s Hotel: The Allerton...” NYT 1 Feb 1920; Landmarks Preservation Commission, March 18, 2008, Designation List 402LP- 2296. The Allerton 39th Street House, 145 East 39th Street, (aka 141-147 East 39th Street).

[18] New York’s Most Exclusive Hotel Residence for Young Women. The Barbizon. Brochure, c1939. NYHS Hotels Collection. (https://sylviaplathinfo.blogspot.com/2011_01_01_archive.html)