Hudson Rising

Reviewed by Kara Murphy Schlichting

What metaphor captures the relationship between the Hudson River, the cities that line its shores, and the people who plie its waters? Is the river a touchstone by which thinkers trace American ideas about nature? Is it an allegory, teaching those humbled in the face of ecological change to repent humanity's role? Is it the exemplar of the declension narrative present in American environmental storytelling? Or is the river more like a battle cry, rallying those committed to environmental activism and resiliency? Hudson Rising, the new exhibit at the New York Historical Society, contends it is all of these things. This deeply researched, thoughtfully presented, and satisfyingly interdisciplinary exhibit introduces the visitor to myriad people who have used and shaped the river, confronted ecological ruin, and turned towards preservation to mitigate degradation.

Hudson Rising, New York Historical Society. March 1 – August 4, 2019.

Hudson Rising introduces the diverse strands of American environmentalism through the lens of a single environmental feature. The exhibit explores the role Americans have played in the Hudson’s ecological degradation as well as activist’s responses to address environmental decline across the river’s expansive watershed space and two centuries. A focus on environmental thinking allows the exhibit to link Hudson River School artistic imagination with Pete Seeger’s brand of citizen activism aboard his sloop Clearwater. The exhibit is beautiful in the art, installations, and artifacts it uses to immerse the visitor in its history. Through media, paintings, surveyor’s maps, and books—I was particularly struck by how seriously the exhibit takes publications, and the emphasis on books as powerful aspects of this history—human renderings of the Hudson are conveyed.

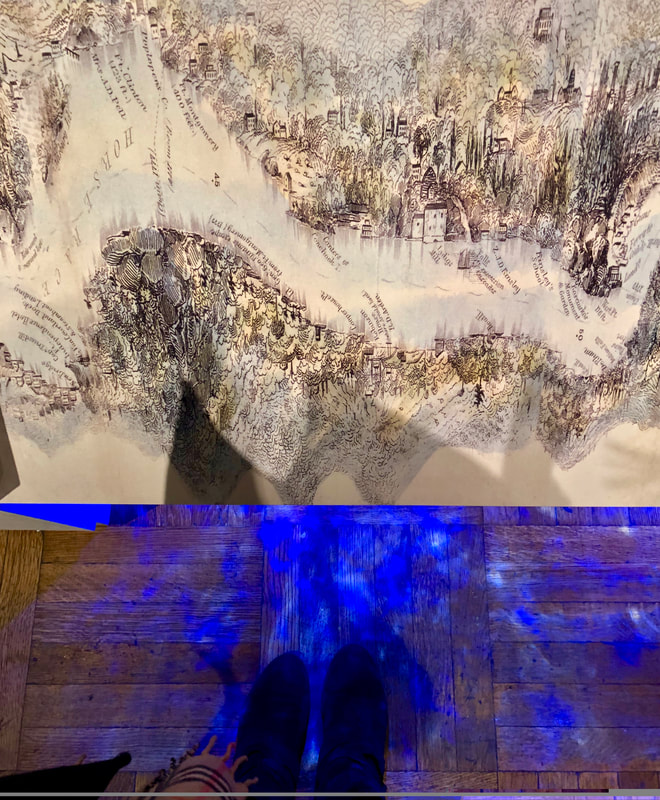

Water shadows play on the floor, under a panoramic map of the Hudson shoreline in Journeys Upriver. The effect of dappled sunlight through trees envelopes the visitor in The Adirondacks section.

The exhibit smartly presents the river, the Hudson River Valley, the river’s source and drainage basin in the Adirondack Mountains, and New York Bay, where the river meets the sea, as a single unit. The exhibit moves geographically through these environmental units across six chronological and thematic units— Journeys Upriver: The 1800s; The Adirondacks: 1870s-1890s; The Palisades: 1890s-1950s; Storm King: 1960s-1980s; The Environmental Movement: 1960s-1980s; A Rising Tide: Today.

As an introduction to Hudson Rising, the lobby sets the scene for the following environmental history of the Hudson River. This space sets the scene an overview of the ecology and European settlement of New York Harbor on one side and a powerful testament to Hudson’s cultural and artistic symbolism on the other: Thomas Cole’s Course of Empire series (1834–1836). The curators interpret the five-painting cycle as an allegory of environmental transformation, charting the rise and dramatic decline of civilization. Cole, the visitor is told, questioned the social costs of the nineteenth century bywords “progress” and “improvement,” a prescient prelude to Hudson Rising’s exploration of human response to anthropogenic environmental degradation. Cole’s paintings are paired with a brief introduction to the ecology of New York Bay and Native American and colonial uses of it. I have read about these paintings; seeing them for the first time together was special. The lobby display alone is worth visiting, and it is but a prelude to the full exhibit. I did pause, however to wonder about “starting” this history at 1800, particularly since this framing keeps colonial relationships, but more importantly Native American relationships, with the river out of the main exhibit. What could these relationships have added to the exhibits overarching questions about resource use and cultural understandings of the Hudson? What ecological challenges wrought by humans predated nineteenth-century industrialization and urbanization?

Introduced to two of the river’s extraordinary attributes (its ecological richness and inspiration to art), the visitor moves from the lobby into the first formal unit of the exhibit, the Journey Upriver: The 1800s. Returning to the oysters introduced in the lobby, Journeys Upriver introduces the wide range of human use of the river, from fishing to brick and iron production to anthracite coal mining. Art is also one of the commodities, the exhibit suggests, extracted from the environment. The Hudson River School’s art is juxtaposed against industrial commodities, remaindering the visitor that humans have always seen both artistic and economic value in the river. Just as the nation’s first artistic school owed its existence to the sublime beauty of the Hudson, the city at its mouth, New York, owed its economic might to its resources and transportation potential. I was struck from the opening of the exhibit by the work it does, perhaps unintentionally, to solidify the idea of the Anthropocene for me. While this term Anthropocene is frequently evoked, here this concept is concretely illuminated. Hudson Rising tells the history of human influence on the river system, both in witnessing the transformations of the past but assessing the present and reimaging the future of the river irrevocably linked to humans.

Beginning in 1807 steamboats made Hudson River journeys cheap and reliable. As trade expanded between river communities New York City, commercial interests reshaped the river. Hardening the river’s soft-edge shorelines and dredging its bottom made a straighter, deeper Hudson ideal for shipping and travel. A clear thread through the exhibit is contemporaries’ concerns that environmental degradation was an inescapable component of development. As the river was developed to facilitate travel, the shallows that once supported coastal biota and protected against flooding were largely lost. For most travelers, the nineteenth-century transformation of the river and its valley symbolized improvement. Yet from the earliest years of development along the river and in its hinterland some travelers recognized that “improvement” was a double-edged sword. The question appears early in the exhibit: should any and all uses of the Hudson be permitted? Was scenic beauty as valuable as economic growth? Did improvement inherently undermine the ecological value of the river and cultural admiration of it? I was struck by how early evidence of environmental consciousnesses appeared. Thomas Cole, famous among the Hudson River School painters, first toured, and was entranced by, the Hudson in 1825. The exhibit effectively pairs Cole’s reflection on nature and development from his “Essay on American Scenery” (1836), with his Catskill Mountain House (c.1845-47): “In this age, when a meager utilitarianism seems ready to absorb every feeling and sentiment, and what is sometimes called improvement in its march makes us fear that the bright and tender flowers of the imagination shall all be crushed beneath its iron tramp, it would be well to cultivate the oasis that yet remains to us, and thus preserve the germs of a future and a purer system.”

Books are presented as essential aspects of this history.

The next two sections, The Adirondacks: 1870s-1890s and The Palisades: 1890s- 1950s examine resource extraction and growing concern about the effects of Adirondack logging and Palisade quarries on the Hudson and its watershed. By the 1870s the environmental effects of logging appeared in erosion and silting. Logging opponents argued for both the popularity of the Adirondacks as a wildness recreation destination and the importance of the Hudson as a commercial artery. This history of resource extraction and activists responses to it is presented effectively alongside the images from Seneca Ray Stoddard’s bestselling guidebook, The Adirondacks Illustrated (1874), which run in a large slideshow projected on a wall. Stoddard argued for forest conservation with his photographs. He presented his photographs as lantern slides as public exhibits. His audience included the state legislature, the members of which he helped convince to create Adirondack Park in 1892. Perhaps it was wishful thinking, or just the quality of the exhibition’s immersive, artistic installation, but looking at an early copy of Stoddard’s text, presented alongside an unvarnished slab of lumber, I thought I could catch the woodsy smell of fresh-cut lumber.

The exhibit presents the creation of Adirondack Park and outlawing of logging on state land there as a forerunner to wild and wilderness and public government intervention. It is also, when paired with the fight to preserve the Palisades, clearly a forerunner to a different type of environmental preservation in the form of recreational space adjacent to cities, not just wilderness accessible by a certain group of recreationalists. A similar conservationist story, the visitor is made to understand, unfolded along the Hudson’s banks in New Jersey. In the late 1800s, quarry companies were blasting the Palisade cliffs with dynamite. Citizen advocates fought back and supported politicians who in 1909 created the Palisades Park. The exhibit underscores the evolving links between environmental consciousness and the Hudson. “Previously it had been artists and writers who recognized and most powerfully expressed the experience of the Hudson and its surroundings,” an exhibit panel explains. “With the creation of a park in the Palisades, a government agency now set the stage for millions of ordinary Americans to create their own experiences. The result was a heightened awareness of nature and growing support for conservation.”

The Hudson Highlands: 1960s-1980s section explores how activists helped spark the modern American environmental movement, fighting on multiple fronts: against untreated sewage, industrial pollutants, power plants, and their impact on Hudson River fish species, particularly striped bass. Con Edison proposed a new hydroelectric plant on Storm King Mountain in the Hudson Highlands in 1962, but due legal action and citizen mobilization activists—seventeen years’ worth—successfully blocked the plant’s construction. The Legacy of Storm King is clear. Hudson River environmental activists emerged from the contest armed with a new set of legal tools to face environmental threats. The Storm King established precedent for the right of citizens to sue on behalf of environmental concerns; due diligence by federal agencies to investigate all relevant facts before granting approvals for projects with potential environmental ramifications; and legal protections for the scenic, historic, and recreation character of a place. Storm King also led to the organization of important environmental organizations including Scenic Hudson, the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association (now Riverkeeper), and Hudson River Sloop Clearwater. This is an engaging and powerful section of the exhibit. Striped bass, a species threatened by the Con Edison plant, and other fish native to the Hudson River swam in an aquarium alongside the exhibit’s explanation of the Storm King fight. Seeger’s 1966 song “My Dirty Stream” plays on nearby headsets. “sailing down my dirty stream/ still I love it and I'll keep the dream/ that some day, though maybe not this year/ my Hudson river, will once again run clear.” I sat, listened, and couldn’t help but be moved.

Pete Seeger’s “My Dirty Stream” on audio.

With “A Rising Tide: Today” the exhibition concludes by considering the Hudson of today and tomorrow. This concluding section successfully staves off any attempt by a visitor to leave with an uncomplicated assessment that “the Hudson is cleaner! Success!” The exhibit concludes by pointing out two ongoing environmental challenges, the river’s continued PCB contamination and legal battles over remediation, and the threat of climate change. Despite the successes of 1960s and 1970s environmental activism, the work to reclaim the Hudson from the legacy of pollution continues. PCBs, an insulating chemical agent, still threaten the river ecosystem. This point is particularly effective as it is presented alongside a material artifact of the contemporary river, a New York State Department of Environmental Conservation “catch and release” sign warning against consuming Hudson River fish. Due to PCBs contamination from GE plants, in the 1980s the Environmental Protection Agency declared a 200-mile stretch of the Hudson a Superfund site. Even today the EPA considers catches from this region unsafe for consumption by children under fifteen and women under fifty. The exhibit underscores the threat: “The government’s message is clear: caution strongly advised. GE anticipates it will be fifty-five years before the fish are safe to eat.”

What climate change portends for the Hudson is still unfolding, but, as the exhibit shows, many of the proposed strategies use the river’s own ecology to rebuild resiliency and prepare for what’s to come in a post-Superstorm Sandy New York. In this final section the exhibit shifts to futurist lab. The final visual is a five minute media installation of a full tidal cycle and storm. The installation explicates the Living Breakwaters project by landscape architecture firm SCAPE, a project designed to lessen impact of storm waves by reducing or reversing coastal erosion. Continued contamination and the need for engineering projects in response to climate change mean there is no easy way to wrap up an environmental history of the Hudson River. It also asks visitors to contemplate the ways in which industrial and commercial use of the river have come up against environmental consciousness an activism—while these ideas look different in the twenty-first century, they are not new, but part of a continual evolution of thinking about the environment. And given the rapid environmental changes anticipated for the river in the coming century, the Hudson’s communities may have to rethink these ideas again in the future. The river, Hudson Rising explains, has been central to both the nation’s history and to how Americans have understood their relationship to the natural world. Yes, humans altered the river, but Hudson Rising reminders the visitor that the river environment also shaped industrial development, commerce, tourism, and environmental awareness. Hudson Rising encourages visitors to see the long, entangled history between the river and its communities.

Kara Murphy Schlichting is an Assistant Professor of History at Queens College, CUNY. She is the author of New York Recentered: Building the Metropolis From the Shore (University of Chicago Press, 2019).