Anne Fleming's City of Debtors: A Century of Fringe Finance

Reviewed by Erin Cully

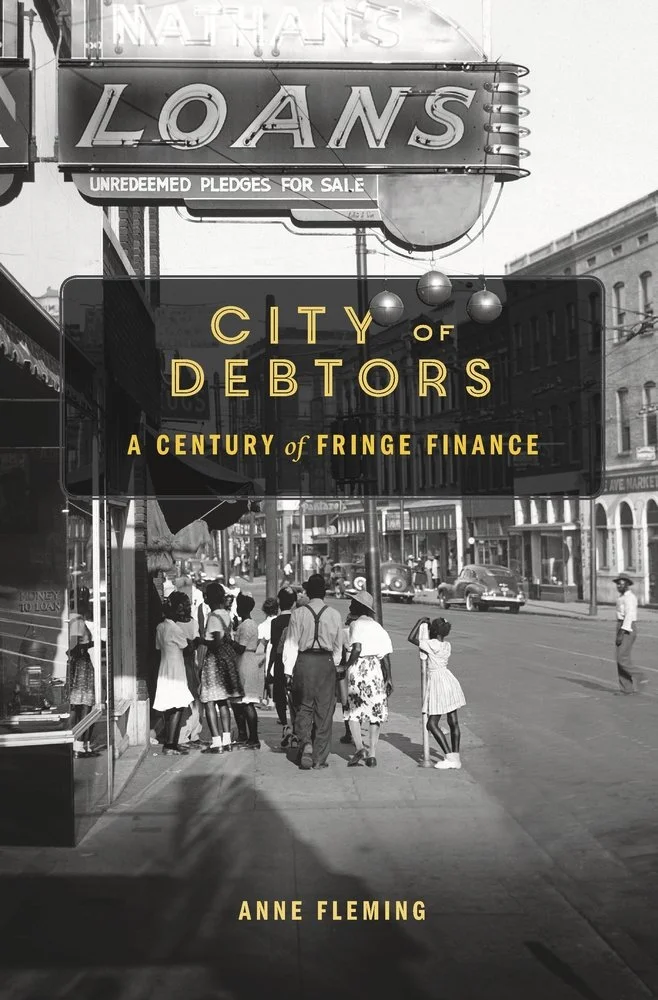

City of Debtors: A Century of Fringe Finance

by Anne Fleming

Harvard University Press, 2018

376 pages

The commercial streets in Flatbush are dotted with storefronts advertising rent-to-own furniture sets and appliances. Pawnbrokers and payday lenders call out to passersby, promising “dollars now” in exchange for gold or a paycheck. Many Americans are accustomed to buying consumer goods by swiping a credit card, but for low-income families in New York and elsewhere, access to credit is limited. Small-sum lenders, pawnbrokers, and furniture stores offering installment plans are often the only recourse for households whose economic circumstances threaten to deny them access to the consumption habits that have defined American freedom for most of the twentieth century. These forms of credit have a high price tag, and goods purchased can end up costing several times more than if bought in cash. Families denied access to conventional forms of credit know all too well how “extremely expensive it is to be poor,” as James Baldwin put it.

In City of Debtors: A Century of Fringe Finance, Anne Fleming, a professor of law at Georgetown University, examines the ways in which a society that accepts the market as the fundamental basis of economic life copes with the inequalities the market creates. How, if at all, can we secure “justice under capitalism?”

Using court records, legislative papers, and the archives of philanthropic groups, Fleming depicts the experiences of New Yorkers whose only way into the consumer economy has been through loans from often unscrupulous lenders. The book examines the reaction of lawmakers and reformers to the so-called “bad bargain” foisted upon small borrowers, and the maneuvering of industry leaders to the changing attitudes toward small-sum lending.

Fleming’s story covers most of the twentieth century, beginning in the 1910s when small-sum lenders became the target of Progressive reformers. The poor, who it was agreed “now and then, need to have money,” found their wages insufficient to cover the necessities of life. They were left with no other option than lenders who devised ways to charge high rates despite the strict usury laws of states like New York. Some lenders preyed on borrowers by burying clauses deep in the paperwork that allowed the loan to be contracted in a state with laxer usury laws, such as Maryland. One lender instructed staff to feign ignorance in front of borrowers. If asked a question, an instructional guide read, “Hunch your shoulders and say you don’t know much about it.” Other lenders charged fees without disclosing that these would inflate the overall cost of the loan. Borrowers sometimes challenged these practices in court, but ingenious lenders found endless ways to skirt the laws.

Populist politicians like Fiorello La Guardia made “loan sharking” into a politically tractable issue. La Guardia, who bragged of being able to 'outdemagogue the best of demagogues,” found it easy to attack the high rates exacted by small-sum lenders. While many politicians lambasted the perceived greed of small-sum lenders, few questioned whether the market ought to be tasked with allocating credit in the first place.

Lenders who tired of playing whack-a-mole with the courts pivoted away from their law-evading ways and instead sought to rewrite the laws in a way that they hoped would appease populists and increase the profitability of the industry. They partnered with reformers at the Russell Sage Foundation, which had long made it their mission to defend working-class creditors against loan sharks. Together, the two groups devised legislation that addressed the most egregious abuses in the industry while making a case for the reasonableness of higher interest rate ceilings. This coalition was successful in pushing the Uniform Law through a dozen state legislatures, including New York’s in 1932. The reform legislation capped interest rates at 3.5% per month and outlawed the tacking on of fees, the garnishing of wages, and the use of “confessions of judgement,” which lenders had often surreptitiously made borrowers sign in order to preempt lawsuits.

While loan sharks captured much of the public imagination, “policy entrepreneurs” such as Persia Campbell attacked another practice which often burdened low income families: installment plans. Furniture stores selling shoddy merchandise mushroomed in poor, often immigrant neighborhoods like Harlem, trapping buyers in an unending cycle of debt. These sellers often used deceptive methods to keep debtors on the hook and make it easier to repossess goods. If a family purchased a couch on year and a bed the next, the contract they signed often contained a clause that allowed the seller to repossess both the bed and the couch in the event the family defaulted only on the bed payments. Persia Campbell focused her attention on another egregious installment scheme: the “freezer food” plan. Here, door-to-door salesmen tempted poor families with the purchase (on credit) of a freezer and a food delivery subscription (both of which often proved to be bad quality). Because of the legal distinction between lending money and extending credit for the purchase of goods enshrined in the “time-price doctrine,” installment plans fell beyond the purview of usury laws and often cost borrowers several times more than retail price. Moreover, frustrated consumers were often left without recourse because sellers frequently sold the debt to finance companies which were insulated from liability of any claim made by the buyer. For example, if the freezer proved faulty or the food delivered, inedible, finance companies could not be held responsible. Campbell was appointed to Governor Averell Harriman’s cabinet, where with dogged persistence and skillful brokering, she was able to shepherd the passage of the Retail Installment Sales Act of 1957, which placated lending groups with increased interest rate caps in exchange for stricter disclosure rules.

Litigation in the wake of the the Retail Installment Sales Act did not prove transformative. The unprofitable nature of prosecuting lenders created perverse incentives, including having borrowers pay their legal fees by recruiting other clients. The most effective tool in the arsenal of the upstart lawyers who accepted these cases was the claim that contracts were “unconscionable” considering the circumstances of their clients. Some lawyers attempted to demonstrate that small-sum loans were unconscionable in general, but these attempts went nowhere since “judges refused to turn the shield of unconscionability into a sword by granting borrowers the power to sue and collect punitive damages for lenders’ unconscionable acts.” Thus the courts presented only a narrow, and often expensive, avenue to justice in the face of predatory lending.

In 1970, Senator William Proxmire despaired that “the failure of private enterprise to meet the legitimate needs of the poor is becoming a stain upon the American conscience.” Little thought was given to whether private credit could, in fact, remedy or even palliate poverty. Proxmire’s call to action engendered few changes. Double digit inflation in the seventies caused banks to shun small loans, and the subsequent wave of consolidation in banking has left large swaths of America “underbanked” or “unbanked,” with little to no access to the private banking system. In these banking deserts, most of which are in low-income communities of color, consumers resort to high interest purchasing plans to furnish their homes and keep up with the demands of twentieth — and twenty-first —century life.

In a lucidly written legal history, Fleming demonstrates how Americans have attempted to deal with the challenges of sustaining consumption in a credit economy marked by high levels of inequality. Fleming argues that the small-sum lending industry did not “capture” the regulatory system, and that successful regulation emerges only when industry leaders acted in coalition with policymakers. Her evidence suggests this was indeed the case for the period leading up the the 1970s, when a dual commitment to Keynesian economic and poverty reduction schemes led policymakers to be both strict and sympathetic toward small-sum lenders. Things appear to have changed. Last week, the Trump-appointed chairman of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Mick Mulvaney, enjoined bankers to ramp up their lobbying efforts. Mulvaney, who received half his campaign donations from the finance industry, promised at a meeting of the American Bankers’ Association to make the bureau “work not only for those who use consumer financial products and services but also for those who provide them.” The commitment to poverty-relief shares by progressive reformers also seems to have waned. Periodically, the idea of using the postal service as a banking system for the poor is revived, most recently by Kirsten Gillibrand. It bears asking whether the incremental reforms on private credit enumerated in Fleming’s book can pave the way to justice under capitalism, or whether this history provides evidence of the impossibility of such a task.

Erin Cully is a PhD candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center.