Art's Great Good Place? Warhol's Silver Factory and Its Legacy

By Jeffrey Patrick Colgan

Brillo Boxes, 1964. Screenprint and ink on wood. Photo by author.

Andy Warhol is a famous artist. With his platinum blonde wig, cosmetic surgery, and cool gaze resting atop impossibly high cheekbones, his visage alone is known by almost every American. So too his art, with its repetition, immediacy, bold splotches of non-gradated color, and mass-culture subject matter. For many outside of the art world he alone represents 20th Century visual art. Within the art world, and the adjacent fields of art history and the philosophy of art, the biography and artistic output of Warhol—endlessly examined and discussed as it is—primarily repeats the same few narratives.

There is the Andy Warhol that incorporated celebrity into both the processes of art-making and the promotion of his artistic brand. There is the Andy Warhol that led to the demise of the convention that art and business are opposing and antagonistic pursuits.

And there is the Andy Warhol that portrayed the quotidian, that perceived and engaged with the latent power of public images and brands, and that worked to blur the boundary between art objects and everyday objects—what philosopher and critic Arthur Danto called mere real things.[1]

Less appreciated is the Andy Warhol who pioneered a cultural structure that would shape and exemplify crisis-era New York City’s cultural underground. The Factory model, epitomized by the ‘Silver’ Factory on East 47thStreet, utilized a porous social space to assemble an ever-changing coterie of eccentrics, artists, socialites, and art world operators in the pursuit of social intermixing, exchange, and—mostly for the benefit of Warhol himself—artistic production. Here, cultural producers met, collaborated, showcased, and participated in artistic ventures within the physical space of the Silver Factory—so called for the aluminum lining installed by Factory manager Billy Name. It was both a space and a scene, a significant cultural institution that existed beyond the realm of mainstream culture. The Silver Factory served as an antipode to the major cultural institutions and galleries that had previously held sway over the art world, and was the first destabilizing step towards the fractured underground cultural scenes of the 1970s and 80s—New York City’s era of financial and political crisis.

The Whitney Museum’s new retrospective, Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again, provides a sweeping overview of the artist’s work. The rooms are curated (mostly) chronologically from Andrew Warhola’s first commercial drawing projects to the erotic sketches that he composed on the side; from his first experimentations with pen ink reproduction techniques to his ‘discovery’ of screen printing, which precipitated one of his most productive periods that included Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962) and Brillo Boxes (1964). The exhibition accounts for Warhol’s ‘retirement from painting’ (1965) by including footage of his multimedia project—and collaboration with the band the Velvet Underground--The Exploding Plastic Inevitable as well as film screenings and his famous screen tests (extended footage of often uncomfortably still models). From the period after Valerie Solanas’ assassination attempt, when he slowly returned to painting, curator Donna da Salvo has chosen his collaborations with Jean Michel Basquiat, his renditions of the Last Supper, and his massive representations of Rorschach ink blots. The scope of the retrospective excellently illustrates both Warhol’s personal and artistic trajectory as well as a changing New York and a changing art world. We see Warhol find his footing, grow in confidence and influence, and—in the end—question everything.

The Last Supper in Camouflage, 1986. Photo by author.

One of the most compelling aspects of the exhibition is the space devoted to Warhol’s ‘middle period’, after he had found success in the art world and was leaving painting behind yet before the 1968 assassination attempt by Solanas. This period roughly coincides with Warhol’s residence at the Silver Factory (1964–1968), and it was there that his legacy as one of the 20th century’s most influential artists and cultural entrepreneurs was forged. This is due not only to the work created there but also to the unique constitution of the Factory itself. Distinct from the bohemian cafes and academic halls that preceded it, the Silver Factory facilitated a novel degree and type of social mixing: inner-city drag queens mingled with rebellious socialites, amphetamine addicts yammered on with the Ivy League posh, mainstream art successes gave deference to Factory eccentrics.

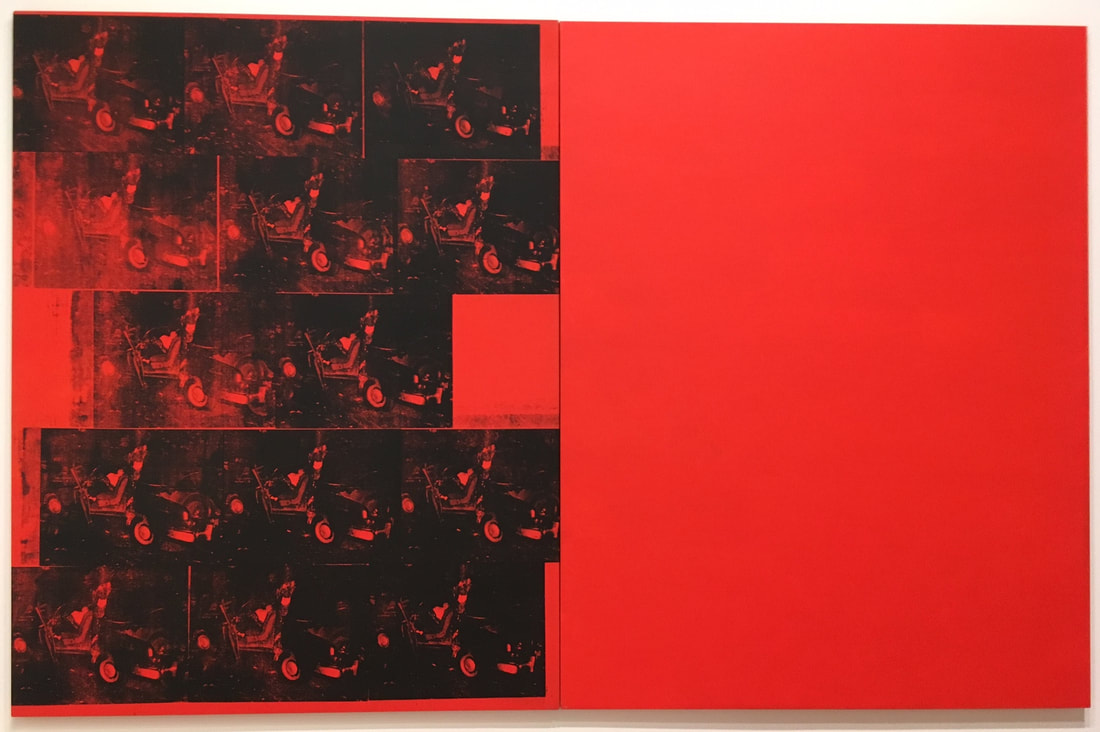

This mixed body of socializers also served as a willing pool of impromptu art-making participants, especially as Warhol entered into his film period (starting in 1965). He saw the attendees of the Factory as subjects and collaborators. Here were actors for films, models for portraits; and throughout Warhol relied on the Factory crowd for ideas and inspiration. Consider in the early 1960s, when Warhol invited to his studio Met curator Henry Geldzahler, art dealer Irving Blum, gallery manager and promoter Ivan Karp, and filmmaker Emile de Antonio. Furnishing his new reproductions of commercial objects, he asked his guests if these works could still be art, even when they lacked the painterly affects of drips and noticeable brush strokes. Years later even, Warhol would drastically change the subject-matter of his art in response to Geldzahler’s advice: “It’s enough life; it’s time for a little death.” Warhol responded by producing works with a darker tone, such as “Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times” (1963) and “Electric Chair” (1964)—both of which are included in the Whitney exhibition.

Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times, 1963. Silkscreen ink, acrylic, and graphite on linen, two panels. Photo by author.

Beyond the mixed crowd and pool of potential collaborators, the Silver Factory itself became a quasi-artwork, as the atmosphere and exploits of the participants grew more performative and attracted and enthralled cultural consumers. Though all socializing has its performative elements, the Factory crowd pushed these elements to new heights, assuming public personas and creating spectacle and controversy for those that wandered within its silver walls. The popular footage of Warhol and Factory habitués feigning ignorance and incomprehensibility for interviewers and visitors serves as a prime example.

Most striking, and perhaps problematic, of this meta-level performance art was the crafting of celebrity from within the ranks of the Factory crowd. Warhol, by means of his films and cultural prominence, fashioned celebrity icons from his collaborators—often times with tragic consequences. Edie Sedgwick, one of the Factory’s so-called ’beauties’, rose rapidly to stardom due to her roles in Warhol’s films and her constant public appearances alongside him. Warhol crafted her celebrity status yet watched with seeming indifference her downward spiral through drugs and mental illness until her death from a drug overdose in 1971. This, amongst other examples, has given rise to a frequent, though not unanimous, reproach from Silver Factory participants that Warhol betrayed a disturbing lack of interest towards the well-being of his collaborators.[2]

Established by Warhol in 1964 and abandoned for Union Square offices in 1968, the Silver Factory’s existence accompanied the industrial and financial fall of New York City. Prompted, in part, by the rise of container shipping in the late 1950s and the decline of the port, Manhattan’s deindustrialization was in full swing by the 1960s. Middle class families left the City for the suburbs, with neighborhoods being filled with recent immigrants and public housing or simply abandoned and left to ruin. When Warhol left the Silver Factory, not only was there a notable difference in the mood of the Factory crowd—with in-fighting, drug use, suicide, and jealousy compromising the space’s open ethos—but New York itself had a decidedly different and darker mood. Post-war optimism had given way to the acknowledgment of a city in economic and infrastructural crisis.

Simultaneously, New York’s cultural realm underwent profound developments—and the Silver Factory occupied a key position during this time of change. In the 1960s the cultural apparatus of New York City began to fracture, as alternative performance venues (e.g., La Mama) opened and competed with landmark institutions; small galleries began opening in SoHo; and loft spaces became fashionable host sites for performances, exhibitions, and socializing. With the diminishment of the hegemonic cultural institutions came a broadening of taste and a general embrace of experimentation and underground culture. Warhol embraced and propelled this shift, using his symbolic retirement from painting not only to declare himself a multimedia artist but also to signal his newfound interest in underground art and culture.

The emphasis on the underground and the avant-garde, the distance from the mainstream cultural institutions, and the embrace of collaboration and multiple media became characteristic of the venues, clubs, and scenes of 1970s and 1980s New York. Performances at La Mama, Judson Memorial Church, East Village store fronts, and even venues like CBGBs embraced this format. And though not solely derived from the Silver Factory, Warhol and the space that he helped create played a pivotal role in blurring the lines between the various social and artistic identities, replacing the 1950s and 1960s cultural hierarchy with the cultural maelstrom of the 1970s.

There is an essential parallel to be drawn between the art-making practices of the Silver Factory and Warhol’s embodiment of the artist as cultural entrepreneur—someone who creates and purveys over both a scene and a space, and who maintains an economic connection to the space. Though Warhol’s works are often seen as solely his, his process was anything but solitary. In preparation for his “Boxes” exhibition at Stable Gallery in 1964, the Factory floor was covered in boxes of various size and in various stages of completion—arranged in orderly lines, while Warhol and his assistant carried on the work of screen printing, setting to dry, and spot-finishing. During the performances of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, the music was accompanied by projected images and designs, light shows, on-stage theatrics, and happening-esque performances within the audience (most notably Ondine and Brigid Polk injecting friends with amphetamines through their clothes)—the result of a cast of collaborators. Furthermore, Warhol’s artistic ideas were often given to him directly by friends and acquaintances. This separation of the individual artist from not only the detail of art production but also the generation of ideas, illustrated a new manner of being an artist. In the same way that Walter Benjamin identified that mechanical reproduction degrades the status of the art object from its place of privilege, so too does the Factory setting degrade the status of the artist—no longer was cultural production beholden to the myth of the lone genius; the artist was remade as organizer, collaborator, and entrepreneur.

Warhol’s status as a cultural entrepreneur is approached, perhaps, only by La Mama’s Ellen Stewart, who created the city’s first significant home to avant-garde theatre. Both Warhol and Stewart shifted the gaze of reviewers and consumers away from the traditional institutions and ways of interacting with art and artists. Art, artists, and art-making departed the sanctioned halls and galleries, spilled out onto streets and into homes, and forced representatives of the old art world downtown.

Retrospective exhibitions, by definition, highlight the personal trajectory of the artist and the cultural-political developments of their contemporary world. What makes the Whitney’s Warhol exhibition unique is that the visitor is able to see a monumental figure impact the developments of their own, of our own, cultural world as well as play a vital role in the rapid expansion of New York’s cultural underground. One is struck by the fact that in the cultural scenes of the 1970s and 1980s we should, at least in part, see the DIY emulations of the Silver Factory model. Though Warhol in his later years shifted away from his role as host and collaborator, his experimentalism, his cultural entrepreneurship, and the legacy of the collaborative Silver Factory model remained palpable in the Downtown underground—and the Silver Factory remains a critical precursor to New York’s current underground scenes.

Jeffrey Patrick Colgan is one of the founders of the Network for Culture & Arts Policy (NCAP), the producer of the DROP DEAD podcast series, and a writer on political and social philosophy. He, along with Jeffrey Escoffier, is writing a book on the economic crisis and cultural creativity in 1970s New York City.

Notes

[1] Danto, Arthur. "The Art World revisited: comedies of similarity." Beyond the Brillo box: The visual arts in post-historical perspective. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux (1992).

[2] See comments made by both Ronald Tavel and Steven Koch in the PBS Documentary Andy Warhol: A Documentary Film. Warhol, Andy. "A Documentary Film." Ric Burns, USA (2006).

—

Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again, Whitney Museum of American Art

November 12th, 2018 - March 31st, 2019