The Astor Place Riot: Blood on the Cobblestones

By Fran Leadon

Part 2 of a two-part series commemorating the 175th anniversary of the Astor Place Riot.

“This cannot end here,” Philip Hone wrote in his diary on May 8, 1849, the day after English tragedian William Macready was shouted off the stage at the opulent Astor Place Opera House. “The respectable part of our citizens will never consent to be put down by a mob raised to serve the purpose of such a fellow as Forrest.” [1]

Astor Place in 1854, after its opera house was repurposed as the Mercantile Library, or Clinton Hall. William Perris, civil engineer and surveyor. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-ff60-a3d9-e040.

Edwin Forrest, the great American-born tragedian, was locked in a bitter feud with Macready, and it was Forrest’s fans who had disrupted Macready’s performance of Macbeth. Against the backdrop of the 1848 revolutions in Europe and coming amid social unrest at home, the Macready-Forrest rivalry became a referendum on what it meant to be a New Yorker and an American.

Macready was supposed to return to the opera house on May 8 to play the lead in Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Richelieu, but after the fracas the previous night the house remained dark. Forrest, in residency at the Broadway Theatre, one mile south of Astor Place, went on as scheduled, playing the same role.

The following evening, May 9, Forrest presented his “Indian drama” Metamora; or, the Last of the Wampanoags, while the managers of the opera house put on The Merry Wives of Windsor without Macready. Earlier that day, a petition had appeared in newspapers, signed by forty-seven influential New Yorkers, including Washington Irving and Herman Melville, promising Macready there would be no more trouble if only he would come back for a second try. He agreed, and a redo of Macbeth was scheduled for the next evening, Thursday, May 10. Forrest, at the Broadway Theatre, was scheduled to play Spartacus in The Gladiator.

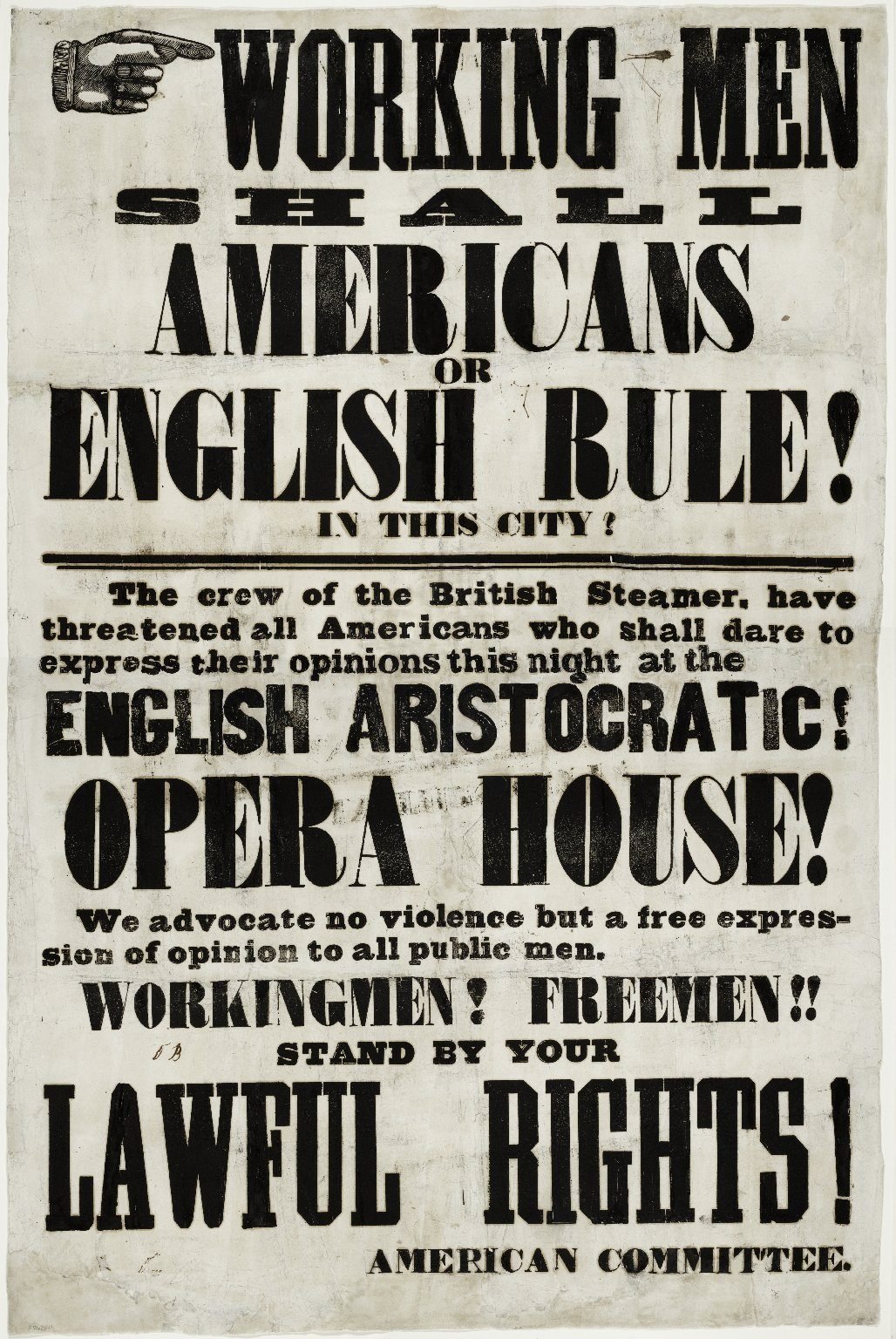

The incendiary handbill that inflamed class tensions before William Macready’s second attempt to play Macbeth. Folger Shakespeare Library https://images.folger.edu/.

Incendiary handbills appeared around town, apparently the work of Isaiah Rynders and his associate Edward Z. C. Judson, penname “Ned Buntline,” a dime novelist, theatrical agent, and general ne’er-do-well. The handbill was a call to arms, a plead for “Working Men” to decide whether the English or Americans ruled the city. Rynders and Judson even cooked up something about the crew of a “British steamer” threatening any New Yorkers who exercised their right of free speech at the “Aristocratic Opera House.” It was preposterous but effective, and as Macready prepared to go onstage, a large contingent of “Forresters” again infiltrated the opera house.

Police stood in the aisles. When Macready made his entrance in the third scene and delivered his portentous first line, “So foul and fair a day I have not seen,” he was greeted with both thunderous applause and a chorus of hisses. After some hesitation, police chief George W. Matsell ordered the hecklers arrested; they were herded into rooms beneath the boxes, where, under guard, they remained until early the next morning.

But the police quickly lost control of the situation outside, where a large crowd began hurling paving stones at the theater, breaking the windows. When Judson brandished a sword and egged on the crowd he was arrested and taken into the theater, but the assault continued unabated.

Mayor Caleb Woodhull had earlier ordered Major General Charles W. Sandford, commander of the 7th Regiment of the New York State Militia, to muster his troops in case things got out of hand. Sandford ordered attachments of infantry, cavalry, and artillery to the drill hall at Centre Market to await instructions. Pleading bad health and grief over the sudden death of his son, Woodhull spent the evening at his home on Beekman Street, just south of City Hall.

Robert McCoskry Graham, the eighteen-year-old son of a prominent Washington-Square family, watched the unfolding situation from the second-floor window of his aunt’s house on the west side of Broadway, opposite Astor Place. Hone left his home at the corner of Broadway and Great Jones Street and walked the four blocks up to the opera house, but when he saw the immense crowd, later estimated at 10,000 people, he thought better of it and walked home. On his way down, he passed Sandford marching the 7th up Broadway to confront the mob. Hone noted that the regiment was “well armed.” [2]

But Sandford had only three hundred men, insufficient to quell such a large crowd. As soon as they turned from Broadway into Astor Place, Sandford and his troops were enveloped in darkness—someone had doused the gas lamps along the street. Nothing happened for a few seconds, but then the crowd started throwing paving stones left piled around a sewer excavation. The crowd was so dense the troops couldn’t hold their lines and were forced onto the sidewalk in front of the opera house, where they stood four deep as the crowd pressed them against the wall. Facing Dorothea Astor Langdon’s opulent mansion directly opposite the opera house, Sandford’s soldiers began falling to the pavement as they were struck with projectiles.

Inside the opera house, the play was winding down. At nine o’clock Macready delivered Macbeth’s defiant final speech, now laden with new, urgent meaning.

I will not yield,

To kiss the ground before young Malcolm’s feet,

And to be baited with the rabble’s curse.

Macready made his exit and huddled backstage. As soon as the play ended, he slipped out unnoticed, blending in with the audience as it exited through doors on the 8th Street side of the building.

On Astor Place, Sandford’s troops tried to move the crowd back with fixed bayonets, but the mob tried to wrest the guns from their hands. Graham, watching from his aunt’s window, saw the militia and crowd surging back and forth “like wheat in the wind.” [3]

This is where the city’s geography played a crucial role in matters to come: Astor Place, a remnant of a colonial highway called the Sand Hill Road, was short (barely five hundred feet from Broadway to the Bowery) but a bit wider (seventy feet instead of sixty) than most of the cross streets laid out in the Commissioners Plan’s grid of 1811. The Sand Hill Road had followed a meandering course preserved in the angled trajectory of Astor Place, which, when it intersected East 8th Street at the eastern edge of the opera house, resulted in a triangular open space, an unresolved, ad-hoc public square (today’s Astor Place Plaza) big enough to contain a large crowd.

Portrait of Charles W. Sandford, commander of the 7 th Regiment, by Mathew Brady, ca. 1844-60, Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2018667787.

Very few in that crowd were there to riot; as so often happens, most were onlookers. George W. Gedney, a thirty-four-year-old Wall Street silk broker who lived three blocks from the opera house was, like many of the people standing around him, on his way home from work. He stood inside the railing that ran alongside the Langdon mansion, his back to the house, and watched the crowd pelting the soldiers with paving stones. [4] Sandford himself was knocked down, then got up, screaming at the crowd to fall back. His troops would open fire, he shouted. [5]

In the confusion, Brigadier General William A. Hall reportedly yelled, “Fire over their heads!” Sandford repeated the order, and the troops raised their muskets and shot up the brick façade of the Langdon mansion. Sandford had hoped to frighten the crowd into retreating, but it didn’t work—still the rain of stones continued.

Then the carnage began: Hall shouted, “Fire low!” and the soldiers leveled a volley directly into the crowd. [6] Gedney, trapped against the Langdon mansion, was shot in the head and died instantly. Thomas J. Belvin, a boatman, was standing next to him. “I laughed, and so did others,” Belvin later testified. “[Then] I heard a man say, ‘My God, look at this. He’s shot.” [7] Like many other onlookers that night, Belvin assumed the troops were using only blank cartridges.

As bodies fell around him, Belvin ran in terror four blocks down Lafayette Place to the Collegiate Dutch Reformed Church, at the corner of 4th Street. “I don’t know how long I stood there, I was so frightened,” he said later. “I stood there until I heard another banging of muskets, and then I started and ran home as quick as I could; I should not have gone there, if I had known they were going to use lead; I went to see what was going on, like many others.” [8]

Panicked bystanders fled up and down Broadway, down Lafayette Place, and east to the Bowery as the militia opened fire three or four more times. Stephen W. Gaines, a counselor-at-law who lived on East Broadway, had been standing on a pile of boards, watching. When the troops opened fire, he found himself hemmed in by the immense crowd. Henry Otten, a twenty-two-year-old grocer, stood nearby. As Gaines stepped back to take himself out of the line of fire, Otten fell on the sidewalk in front of him. At first people thought Otten was faking, but when bystanders tried to pick him up, they found he had been shot twice—once in the back and once in the stomach. He died a short time later.

The dead and wounded were carried to police stations or laid on the counters of drugstores and barrooms. Some were carried to Jones’s Hotel, at the corner of Broadway and 9th Street, or to Vauxhall Gardens, where billiard tables served as gurneys. Almost all of the people killed were bystanders. The youngest was fifteen years old; six others were under twenty-one. Bridget Fagan, thirty, was killed while walking with her husband two blocks away; Asa F. Collins, forty-five, was shot through the neck on the Bowery as he disembarked from a Harlem Railroad car. Among the several dozen wounded was a Mrs. Brennan, a housekeeper who was walking up the Bowery on her way home from work when she was shot in the thigh, and A. M. Collins, a deacon in the Allen Street Methodist Church. [9]

Graham woke up at four-thirty the next morning and hurried back to Astor Place. On the way he passed members of the 7th Regiment heading home, “fatigued and sorrowful.” [10] He inspected the opera house’s shattered windows and battered doors and stared in wonder at the Langdon mansion, which was riddled with bullet holes. Hone, who also came to see the destruction that morning, thought the Langdon house looked as if it had “withstood a siege.” [11] Behind the railing where Gedney had been standing when he was killed Graham saw three pools of blood, with more on the sidewalk. Around the corner on Lafayette Place, he discovered blood, brains, and skull fragments behind a sewer excavation. [12]

Graham next walked to the Fifteenth Ward police station, at 220 Mercer Street, where he discovered Gedney’s lifeless body on a bench in the back of the room. “Next to him was a man of middle stature, with the whole of the cap of his skull blown off, then came a man who had a throat wound,” he wrote in his diary later that day. “Besides those victims on the floor, lay the body of a young man, and then one with dark whiskers, shot in the right breast, a thin faced man, apparently a mechanic, shot in the neck; a man of somewhat similar appearance, shot in the abdomen and an elderly man, shot in the right cheek.” [13]

At least twenty-two people died; well over a hundred were injured. At least six of the dead were Irish immigrants. [14] “The awful result is before the world,” the Herald reported. [15]

On the afternoon of May 11, protestors gathered in City Hall Park to condemn the city’s violent response to the riot, and in the evening the military cordoned off the streets surrounding the opera house and briefly clashed with angry crowds on Broadway. Forrest, determined to finish his engagement at the Broadway Theatre, played the lead in King Lear. The house was nearly empty.

But already the city’s well-practiced social and business routines were returning to something close to normal. Hone attended a lavish dinner that night at diplomat Aaron Vail’s mansion on Fifth Avenue, where he hobnobbed with Gen. Winfield Scott, Washington banker William Wilson Corcoran, and Washington Irving. The dinner was “sumptuous,” Hone reported, the table “superb.” [16] The next day young Graham exercised at a local gym, went to the dentist, and had his tailor sew new buttons onto his coat. [17]

Macready sailed home for England, while Forrest closed his engagement at the Broadway Theatre by once more playing his “favorite character,” the lead in Metamora. [18] Forrest was facing new scrutiny over recently-published details of his failing marriage, but the crowd was larger than the previous evening and solidly behind him. A cry of “Three cheers for Forrest!” went up after the second act. “Three cheers for Macready!” followed, but was met with one “long, loud whistle” from the Forresters. [19] In the play’s final scene, as Puritans kill Metamora, Forrest’s angry voice rang out through the theater: “My curses on you, white men! May the Great Spirit curse you when he speaks in his war voice from the clouds! Murderers!” [20]

Three months later, an editorial in the New York Herald scoffed at the idea that the riot on Astor Place was the result of anything larger than a theatrical rivalry that spiraled out of control: “Forrest and Macready were simply two good actors, pretty good in particular lines; but it is rather two ridiculous to invest either of them with the responsibility of being the representative of any great principle.” [21]

In 1849, riots, including theater riots, were nothing new in New York, and the Astor Place tragedy came in an era of profound social unrest in New York. But the city’s militaristic response—opening fire on civilians—was something new, and armed violence, or the threat of it, was used again and again in the wake of Astor Place: In the Dead Rabbit Riot of 1857, Sandford again led troops through the streets, this time to confront rival gang factions, a melee that left at least eight people dead. He commanded the militia once more during the Draft Riots of 1863, when a racist insurrection directed at the city’s Blacks turned New York into a battlefield, killing 200 and injuring 2,000. And in 1871, armed troops mowed down forty-seven Catholics protesting the annual July 12 parade by the Protestant Orange Order.

The Astor Place riot, though it has been obscured by time, forever changed the tenor of public discourse in the city. Never again would people take to the streets oblivious of the real possibility of winding up shot to death on the sidewalk.

Fran Leadon is an Associate Professor at the Spitzer School of Architecture, City College of New York, and the author of Broadway: A History of New York City in Thirteen Miles.

[1] Bayard Tuckerman, ed., The Diary of Philip Hone, 1828-1851, II, New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 360.

[2] ibid, 361.

[3] Robert McCoskry Graham, Diary, 1848 Feb.-1849 Oct., MS diary, New-York Historical Society.

[4] Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot at the New York Astor Place Opera House, New York: H. M. Ranney, 1849, 5.

[5] New York Herald, May 13, 1849, 2.

[6] ibid, May 13, 1849, 2.

[7] Account of the Terrific and Fatal Riot, 25.

[8] ibid, 5.

[9] ibid, 29-31.

[10] Graham diary.

[11] The Diary of Philip Hone, II, 361-362.