The Case of Ernest Gallashaw: Achieving Justice in an Earlier Era of White-Backlash Politics

By Robert Polner and Michael Tubridy

After three decades as a New York defense attorney, Paul O’Dwyer was used to championing American underdogs in courtrooms and at the barricades with strikers and protesters. But in the summer of 1966, representing an African American teenager from Brooklyn on murder charges was challenging, to say the least.

In an era when the testimony of police was rarely refuted, O’Dwyer’s 17-year-old client, Ernest Gallashaw, was identified by New York’s Finest as the prime suspect in the shooting of Black 11-year-old Eric Dean—a tragic incident that, before Gallashaw’s apprehension, threatened to plunge the neighborhood into a race riot. The episode proved to be a revelatory moment in a city whose conceit of tolerance was belied by stark economic inequality as well as segregation in housing, employment and schools. Now virtually forgotten, the eruption on poor and working-class streets 15 miles from City Hall was—and still remains—historically significant for signaling New York City’s seething racial tensions and the potential for intense right-wing reaction.

An Irish Passion for Justice: The Life of Rebel New York Attorney Paul O'Dwyer

by Robert Polner and Michael Tulbridy

Cornell University Press

May 2024, 472 pp.

On the night of July 21, 1966, the young Eric was struck in the chest, fatally, and Gallashaw was arrested for causing his death by firing into a chaotic crowd. The shooting took place after sporadic clashes near the unofficial racial boundary of New Lots Avenue, where East New York’s Italian Americans often collided with the community’s Black and Puerto Rican residents. O’Dwyer, a familiar presence in the local news with his crest of white hair, thick eyebrows, and Irish brogue, placed himself at the center of the legal aftermath, shouldering responsibility for Gallashaw’s defense on a pro-bono basis. Gallashaw would go to trial for murder in the fall, drawing close attention from the press.

The combustibility of neighborhood race relations had come as a surprise to many, even perhaps O’Dwyer, who had supported and participated in New York’s interracial civil rights movement since World War II. The younger brother of the former mayor Bill, who presided from 1946 to 1950, O’Dwyer had represented many an activist organization and marginalized individual, both white people and people of color. Among them was Transport Workers Union leader Michael Quill, who had a deadly heart attack after being jailed for leading his members out on a 12-day strike on John Lindsay’s first day in office as mayor in January, 1966. O’Dwyer also defended targets of the Red Scare as well as Black activists fighting for the right to vote and run for office in the Deep South, and he argued before the US Supreme Court, ushering in the end of an English literacy requirement for Spanish-speaking voters. O’Dwyer, in each instance, linked his support of the oppressed to the 1919-21 Irish War of Independence he experienced as a youth. But his tendency to speak his own mind impeded his political career, contributing to his last-place finish in the four-way Democratic mayoral primary of 1965, when he was councilman-at-large for Manhattan. [1] The defeat was itself a reflection of the city’s weakening attachment to FDR’s New Deal and support for racial equality, though he would be elected as City Council president eight years on.

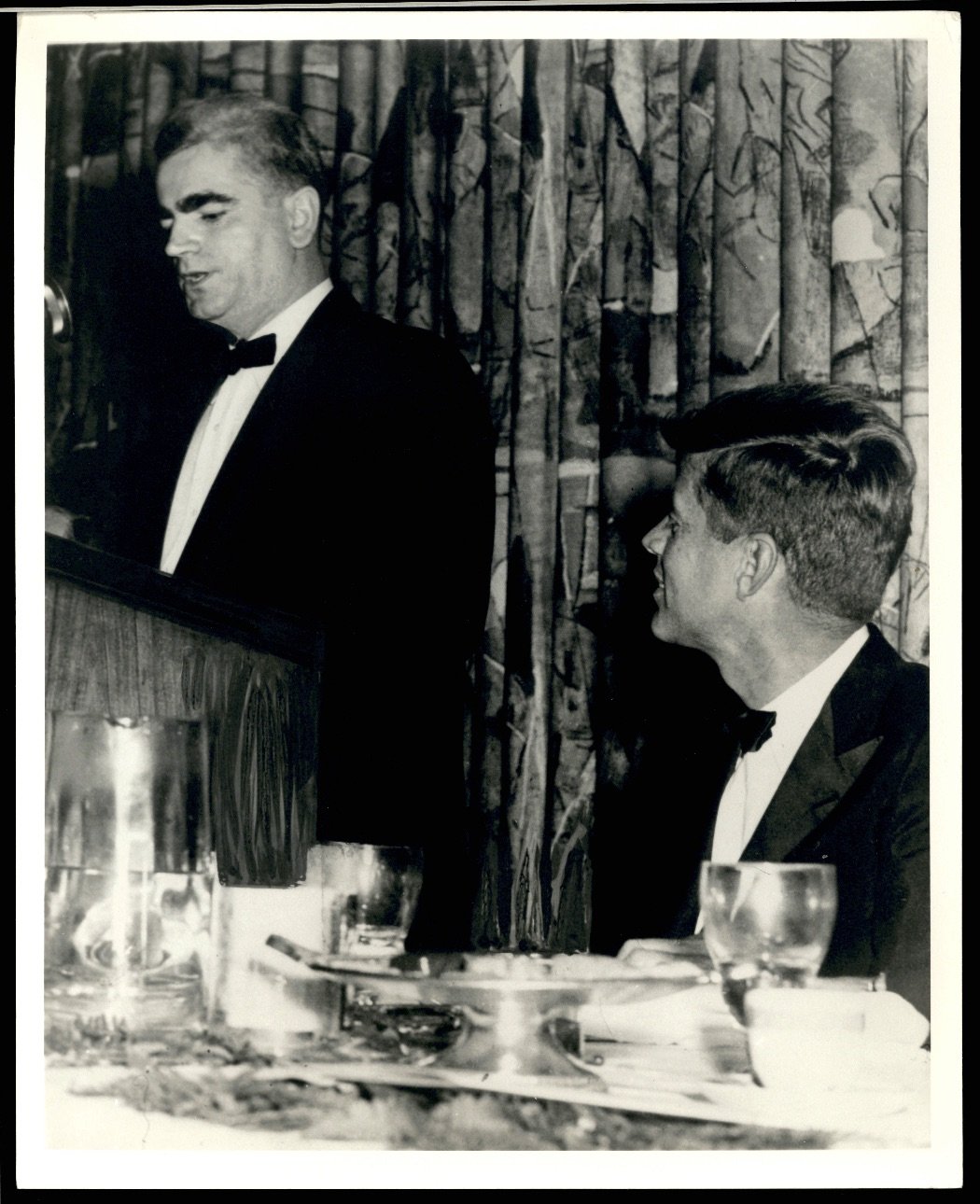

In 1957, the year after John Kennedy was disappointed in his bid for the Democratic vice-presidential nomination, the Massachusetts senator was introduced at the annual dinner of O'Dwyer's Irish Institute on the West Side Manhattan as a future president of the United States. (Credit: New York City Municipal Archives.)

John Lindsay, who became mayor in January 1966, confronted the city’s racial inequities in the context of gathering civil rights movement in the South as well as the recent U.S. Voting Rights and Civil Rights acts. The first progressive Republican to helm the city government since Fiorello La Guardia, he sought to become known as a national spokesman on race relations and urban blight. But this former Upper East Side Congressman wrestled with rising social tensions throughout his entire two terms in office. The postwar values of pluralism, most dramatically symbolized by the breaking of baseball’s color line by Brooklyn Dodger Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson, were tested as crime and poverty spread and middle-class families decamped for the suburbs.

It was early evening when the racial animosity churned in East New York, Brooklyn--so portentously for that struggling neighborhood and possibly others that editors at the New York Times made the events the lead story in the next day’s paper. [2] Lindsay suddenly learned at City Hall that a 3-year-old boy was shot in the stomach at about 5 p.m., so he headed straight to the neighborhood, encountering gang clashes that seemed straight out of West Side Story.

Known for his movie-star looks and refinement, the Ivy League-educated mayor spent hours canvassing the area, exhibiting a peacemaker’s resolve that he would reprise in Harlem after the 1968 assassination of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The mayor walked with aides in the Italian-American parts of the neighborhood, drawing boos and catcalls, and sat with Black and Puerto Rican leaders at a restaurant called Frank’s, where, outside, members of a vigilante group chanted, “Two, four, six, eight—We don’t want to integrate.” [3] Lindsay departed for City Hall, but circled back upon learning of the gun blast that felled Eric Dean.

Cops picked up Gallashaw that night, charging him with the 10 p.m. shooting. The arrest of a Black teen rather than a white youth, or no arrest at all, for the death of the Black child may have prevented further rumors and hostilities. The night ended without additional bloodshed, and Lindsay visited the Dean family’s home to express his sympathies.

In the morning, however, the question lingered: Was Gallashaw anywhere near the gun that was fired? Only circumstantial evidence existed; no weapon was found. Yet the teen was arraigned. The Brooklyn district attorney (DA), Aaron Koota, presented a grand jury with accounts from a trio of adolescent Black witnesses, and the panel returned an indictment.

Gallashaw’s parents at the same time insisted their son was at home when Eric was shot, and the Council for a Better East New York, the Warwick Street Block Association, and the Congress of Racial Equality offered to try to help them. One can only imagine what this family was going through. It was a time when most newspapers referred to the race of crime suspects only if they were Black or Puerto Rican, while five times as many African Americans as whites filled the nation’s prison cells. (The current ratio is about 6:1.) [4]

O’Dwyer’s courtroom experiences dated to the early 1930s, when indigent defendants were parceled out by the Brooklyn criminal court to himself and other attorneys. Through his investigation of the circumstances of Eric’s death, and a powerful spate of reporting by Richard Reeves for The Times, the case against Gallashaw faltered. Late in the summer, Reeves and a Black colleague at the paper, Tom Johnson, reported that two of the young African-American witnesses who had spoken with police amended or disavowed their affidavit statements when the journalists found them—Nathaniel Breaker and James Windley, both 14. [5] The “peculiar circumstances” resulting from these interviews, as Koota put it, soon saw him asking the State Supreme Court to begin Gallashaw’s trial within three weeks instead of the customary three months—and so it did. The DA also had his witnesses placed in a hotel guarded by police for fear that they would be intimidated or even attacked.

Paul O'Dwyer walks in February of 1976, memorial march in New York for Frank Stagg, a Provisional IRA member from County Mayo who died on hunger strike in Wakefield Prison in England that February. To O'Dwyer's right is columnist Jimmy Breslin; to his far left are Bronx borough president Robert Abrams and Bronx congressman Mario Biaggi. (Credit: The Irish People Collection at the IUPUI University Library.)

In part because a judge would not likely have granted bail for Ernest—set at $15,000 and satisfied with a bond—in a first-degree murder case unless he had doubts about the charges, O’Dwyer decided to approach Koota, urging him to return the case to the grand jury. He told the Democratic DA that “the police gave you a fast one,” according to New York Post editor and columnist James Wechsler, but was “brushed off.” [6]

The Times editors gave Koota a full day to comment on witnesses’ disavowals to Reeves, and the DA indicated finally that he would reappraise the witnesses’ sworn affidavits. For O’Dwyer, the development amounted to an unexpected bonus for his client close to the start of testimony. [7]

In front of the multi-racial jury of 10 men and two women that October, prosecutors brought to the stand police officers who described the night of violence and disruption. The trio of boy witnesses also testified for the prosecution, as did Eric’s older sister.

O’Dwyer called many family members and neighbors to the stand, each testifying Gallashaw could not have fired the lethal shot because he was not present when Eric was struck, and as hundreds of cops wearing helmets poured into the community.

The lawyer cast further doubt on the reliability of the prosecution’s witnesses, particularly Windley, who testified that Ernest was holding a gun when Eric collapsed. During cross-examination, O’Dwyer’s questions brought out that Windley was suspended from school three times that spring and had once threatened to beat up a schoolboy who owed him money. [8]

O’Dwyer in the end put Ernest in the witness box—a “surprise,” the Daily News reported, as it exposed the defendant to cross-examination. But the lawyer’s questions underscored that the high school student, who wore a dark suit and blue polka-dot tie, had never before been in trouble with the law.

“On the night of July 21, did you fire a shot that killed Eric Dean?” O’Dwyer asked him.

“No sir,” the youth said in a low voice, leaning forward to hear his lawyer’s next question.

“Where were you that evening?” asked O’Dwyer from the corner of the jury box, 20 feet from the defendant.

“I was home,” came the reply. [9]

On Oct. 21, the jury returned to the packed courtroom after just six and a half hours of deliberations. Judge Julius Helfand requested to hear the verdict from the lead jury member, who then stood. “Not guilty,” he intoned, sparking cheers and applause.

It was a stunning moment, and many of those in the packed courtroom—Ernest’s mother, news reporters and columnists, lawyer-spectators—never forgot it. As O’Dwyer had demonstrated, the police had arrested the wrong man, “railroaded, like it was the Deep South,” recalled Mychal McNicholas, O’Dwyer’s cousin and office assistant, who helped him at the defense table. [10] “He belongs,” Wechsler wrote of O’Dwyer, “to an old-fashioned breed of lawyer whose favorite species of defendant is the underprivileged underdog.” [11]

Ernest’s parents sent a telegram, wiring their son’s lawyer, “At one point, we came to feel that there was no justice for Ernest because he was a black boy. You alone have restored our faith in democracy.” [12]

Paul O’Dwyer, it seemed, had not given up on the possibility for justice. But other New Yorkers had. Three weeks after Gallashaw walked free, the city electorate weighed a question on the ballot as to whether the city should establish a civilian complaint review board to review citizens’ reports of misconduct by police officers. The vote on the modified panel, a Lindsay proposal, killed it by a lopsided 2-to-1 after an inflammatory and racially coded campaign by the Police Benevolent Association, police officials, and conservatives. [13]

But the results of the vote were definitive, with more than 2 million having gone to the polls. The alarming power of white backlash politics—today so omnipresent across America—was out of the bag in New York City.

Robert Polner and Michael Tubridy are the authors of An Irish Passion for Justice (Cornell University Press/Three Hills, May 15, 2024), a biography of the rebel New York attorney Paul O’Dwyer, who fought for civil rights and civil liberties throughout the 20th century.

Polner reported extensively for Newsday, the New York Daily News, and other newspapers. Now a public affairs officer with NYU, he has cowritten or edited four other books, including The Man Who Saved New York, a 2010 chronicle of New York Gov. Hugh Carey and the 1975 NYC fiscal crisis (winner of the Empire State History Book Award).

Tubridy is a researcher, editor, and freelance writer whose work has appeared in Irish America, The Recorder, and Kirkus Reviews, among other publications. With Irish roots on both sides of his family, he writes and lectures on Irish and Irish American literature, film, and history. His blog is called “A Boat Against the Current.”

[1] Francis X. Clines, “Paul O'Dwyer, New York's Liberal Battler For Underdogs and Outsiders, Dies at 90,” The New York Times, June 25, 1998, B9.

[2] Albin Krebs, “Brooklyn Sniper Kills Negro Boy in Race Disorder,” The New York Times, July 22, 1966, 1.

[3] Ibid.; Michael Stern, “Mayor Pays Visit to Family of Boy; Offers Sympathy on Return to East New York; Plea for Peace Made Earlier,” The New York Times, July 22, 1966, 1. (Sidebar to the Krebs article.)

[4] Leah Wang, “Updated Data and Charts: Incarceration Stats by Race, Ethnicity, and Gender for All 50 States and D.C.”, Prison Policy Initiative, Sept. 27, 2023, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2023/09/27/updated_race_data/.

[5] Thomas A. Johnson, “Prosecution Witnesses Allowed to Go Home in Gallashaw Case,” The New York Times, September 18, 1966, 65; Richard Reeves, “Quick Trial Asked for Gallashaw,” The New York Times, September 20, 1966, 42.

[6] James A. Wechsler, “For the Defense,” New York Post, October 20, 1966.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Richard Reeves, “Gallashaw Accused By Boy, 14, on Stand,” The New York Times, October 7, 1966, 1, 29.

[9] Richard Reeves, “Gallashaw Gives His Alibi on Stand,” The New York Times, October 11, 1966, 40.

[10] Mychal McNicholas, follow-up conversation with Rob Polner, July 15, 2020.

[11] Wechsler, “For the Defense.”

[12] “Mr. and Mrs. Gallashaw and Family,” Western Union telegram, October 15, 1966, in the records of Paul O’Dwyer, Subject File: Councilman at Large, 1965–66, Box 5, Folder 77, NYC Municipal Archives.

[13] Ben Houtman, “Police Corruption and the Civilian Review Board,” www.wnyc.org, March 3, 2016, https://www.wnyc.org/story/john-lindsays-civilian-review-board/.