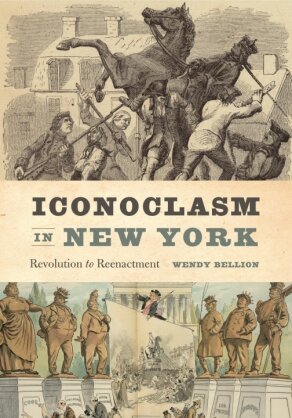

Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment

Reviewed by Benjamin L. Carp

Iconoclasm in New York:

Revolution to Reenactment

By Wendy Bellion

Penn State University Press

272 Pages

New York is a city of destruction. What doesn’t burn by accident, somebody tears down on purpose. When Chip asks Hildy to take him to the Hippodrome in Leonard Bernstein’s On the Town, she replies, “It ain’t there anymore,” which might as well be the city’s motto. Nothing is too sacred to shatter. Nothing is too exalted to escape the city’s brutal contests over money and power.

On July 9, 1776, after a reading of the Declaration of Independence before the Continental Army in New York City, a crowd pulled down the gleaming, gilded statue of King George III that stood in Bowling Green. Henry Chichester took some of the statue’s leaden pieces to Connecticut, where Litchfielders melted them into bullets; Crown supporters managed to spirit away a few of the other parts.

Wendy Bellion’s fabulous Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment offers a lively and intricate retelling of the destruction of the king’s statue. The incident deserves a full treatment because portrayals of it have become so ubiquitous, from Johannes Oertel’s famous Pulling Down the Statue of George III, New York City (1852–53) at the New-York Historical Society to a digital reenactment at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia (2017). With Bellion’s help, we come to terms with the toppling’s recurrence in the nation’s imagination.[1]

The author persuasively analyzes the statue and its destruction: the “ritualistic killing of the British King” might seem to offer an unmistakable symbol of American origins, and yet Bellion discerns a “central paradox”: it “was at once a destructive phenomenon through which Americans enacted their independence and a creative phenomenon through which they continued to exhibit English cultural identity.”[2] Rebels tore the statue to pieces, but Americans had hardly achieved a clean break.

In order for iconoclastic destruction to have meaning, icons themselves have to resonate. Bellion devotes her first chapter to the liberty poles that New Yorkers raised, at first to celebrate the repeal of the Stamp Act and then more generally as a towering symbol of resistance against Parliament. The tallest of them was eighty feet high. The power of the liberty pole derived not just from its height, but from the work of felling and transporting white pines, festooning the poles with signs and symbols, and fortifying two of them with iron. In a diverse city like New York, the poles inevitably gave off variant meanings: a bitter irony for the enslaved, menace and affront to Loyalists, outrage to British soldiers. As much as the Sons of Liberty might celebrate them, they were also nervous about having set up secular idols in their midst. Only when the British troops smashed them did the poles become truly emblematic. In this way inanimate objects become animated.

In celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act, the New York Assembly proposed more formal symbols of gratitude: statues honoring William Pitt and King George III. The legislature finally approved the funds in 1768, commissioning the London sculptor Joseph Wilton. The statues arrived in the summer of 1770. In the center of Bowling Green, the city installed a shiny gilded statue of the king in classical guise, astride a horse. “The equestrian monument was a gleaming embodiment of empire, a centering force in a royalist soundscape, a geopolitical counterpart to the liberty poles, and a target for defacing.”[3] The statue loomed large, but it only lasted six years before rebel celebrants knocked it from its pedestal.

Eighteenth-century New Yorkers had few monuments to call their own, and they wrecked them as fast as they could build them: British soldiers took down five liberty poles in ten years. A 1770 statue of parliamentary hero William Pitt, initially located on Wall Street, lost its head and hands during the Revolutionary War. The transatlantic political conflict transformed the political landscape of pre-Revolutionary New York, inspiring statues of Pitt and the king, as well as defiant liberty poles on the Common (now City Hall Park). Before they were ruined, the liberty pole and Pitt statue were imagined to speak their defiance, while George III’s statue maintained a silent, stately authority in Bowling Green. Having established the icons’ presence amid the sights and sounds of New York, Bellion proceeds to show “how it feels and sounds to destroy a sculptural thing.”[4]

Scholars of material culture usually focus on the creation of things, but as Bellion points out, we also “make culture through gestures of destruction.”[5] Although in the case of the King George III sculpture, both the sculptor and his subject were elite, iconoclasm renders artwork subject to “bottom up” forces. People invested icons with cultural energy that was released in a big burst at the moment of destruction. That energy, Bellion argues, still lingered in the air New Yorkers breathed.

After the Revolution, early American culture derived not just from an imitation of finer British things (like Chippendale furniture or styles of portraiture), but from riots and “performative smashings,” which themselves had their roots in old world rituals.[6] In the book’s second half, therefore, Bellion focuses on the “afterlife” of the destroyed monuments. New Yorkers built on the ruins of the war they’d helped to start. As they replaced the monarchy with a new republic, they held on to relics, reckoned with new icons like George Washington, and reinvented the statue’s image.

Americans continued to grapple with the memory of the British king. That memory, Bellion argues, “became implicated in the hagiography of President George Washington,” whose face was everywhere in paintings, prints, pottery, and coins, but more rarely — at least at first — in public sculpture. “The loss of the royal monument left a void in a deeply ritualized space,” she writes; “New Yorkers sought to refill it with an object that could signal the political succession from one George to another.” As Americans began building statues of the first president after his death in 1799, those images “could not quite shake the phantom of the deposed royal monument.”[7] The empty pedestal in Bowling Green remained until 1818, drawing attention to George III’s absence. Although some contemplated replacing it with a statue of Washington, a permanent public sculpture of Washington didn’t grace the city until 1856, in Union Square.

Even as Washington arose, the rejected monarch kept falling, only to rise again and again: “iconoclasm empowers the very things it seems to erase.” Bellion seizes on a central irony of the King George III statue: the continual reenactment of the statue’s destruction required the statue to be re-raised in the imagination. “The problem with George III... was not that he kept coming back, but rather that he never wholly went away.”[8]

The author powerfully interprets Oertel’s famous painting. Oertel, as “a newly arrived German immigrant unfamiliar with American history,” was a surprising touchstone for future representations of the incident. Bellion suggests that he may well have drawn inspiration from the Hungarian revolutionary Lajos Kossuth and the writer Karl Marx, suggesting that our own image of American iconoclasm is anything but simple or straightforward. In the painting, the statue is roped but not yet fallen: “Oertel evoked revolutions still to be realized, monarchs still to be pulled from their pedestals.”[9]

Later reimaginings of the statue’s destruction — in paintings, prints, and pageants — were more conservative. During the Colonial Revival period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, anxious Anglo-American elites elevated their ancestors’ contributions to the city’s history over those of “recent immigrants, people of color, the newly rich, [and] the laboring poor.”[10] The statue of the king reappeared in patriotic celebrations of Old New York, such as the Hudson-Fulton Celebration of 1909 and the Society of Beaux-Arts Architects’ annual gala of 1932. Artists and audiences seemed to want to domesticate the toppling of the statues: both George III’s statue and its destroyers embodied the city’s British colonial heritage as a cultural shield to ward off immigration and nonwhite participation in the nation’s political life.

Bellion investigates many other pockets of American culture in her exploration of iconoclasm and its fractured meanings. The extent of her research is breathtaking, and her agile wit and engaging style keep the reader striding through the text. Somehow her command of theoretical work from a variety of disciplines manages to burnish rather than deaden the text. Eleven color plates and fifty-one black and white illustrations also give the reader plenty of visual material to ponder.

Scholars of the past, still smarting from the destruction of the Great Library of Alexandria, instinctually regard destruction with horror. But perhaps we can take consolation in the bold new discussions generated by the increased attention — across several fields — to violence, destruction, and iconoclasm. Interdisciplinary work like this teaches readers to see things, sounds, and performances in new ways. In The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900–1940, Max Page writes, “The cultural consequences of a city that gained nourishment by repeatedly destroying and rebuilding itself are profound.” Like Bellion, Page notes “the fundamental tension between creative possibilities and destructive effects.”[11]

With apologies to Thomas Jefferson’s first inaugural address, we are all idolaters, we are all iconoclasts. Much of New York, like the Hippodrome, “ain’t there anymore,” but the city’s ghosts still shape its history. Indeed, its residents insist on it. Amid the national toppling of Confederate statues, New York City removed the statue of J. Marion Sims from Central Park on behalf of the women he exploited. Not content with scuttling like rats, commuters yearn for the restored glories of Penn Station. The avenues are lined with empty storefronts, as Hudson Yards rises alongside dozens of new skyscrapers. Despite all that solid Manhattan schist, somehow nothing is set in stone.

Benjamin L. Carp is Associate Professor of History at Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center, CUNY. He is the author of Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (2010), which won the triennial Society of the Cincinnati Cox Book Prize in 2013, and Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (2007). His current manuscript, under contract with Yale University Press, is about the burning of New York City in 1776.

[1] Wendy Bellion, Iconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019).

[2] Bellion, Iconoclasm in New York, 4. Recent history titles speak to an interest in these fitful and incomplete unravelings: P. J. Marshall, The Making and Unmaking of Empires: Britain, India, and America, c. 1750–1783 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Kariann Akemi Yokota, Unbecoming British: How Revolutionary America Became a Postcolonial Nation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

[3] Bellion, Iconoclasm in New York, 99.

[4] Ibid., 61.

[5] Ibid., 5.

[6] Ibid., 13.

[7] Ibid., 12, 128.

[8] Ibid., 7, 134.

[9] Ibid., 140, 150.

[10] Ibid., 158.

[11] Max Page, The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 3, 259.