A Pathfinder in the Village: Buffy Sainte-Marie on Building a Career in New York’s Folk Music Revival

By Christine Kelly

“The woods are full of folk singers these nights,” reported New York Sunday News writer Walter Meyer on New York’s mid-1960s folk scene, “and so are the cafés, coffeehouses, college campuses, and concert stages.” [1] Remarking on the throngs of young musicians flocking to New York with hopes of becoming professional folksingers – where “no other type of entertainer is growing in popularity with people more” – Meyer voiced his opinion that one could rightly classify only a few of these aspiring professional musicians as genuine artists. “Among this elite,” he declared, “is the unique Buffy Sainte-Marie.” [2]

Meyer was not alone with his observation of Sainte-Marie’s creative prowess or his description of the Indigenous singer-songwriter as “unique.” Of the reams of journalistic copy published about the performer who was then at the precipice of a major career in show business, education, film, and activism, most register qualities about Buffy Sainte-Marie that somehow upset authors’ expectations for a “female folk musician” – a common journalistic designation for women in the revival. [3] Reviews repeatedly described Sainte-Marie as possessing “unusual talent” and “unusual writing skill and performing ability.” [4] Others cast the performer in a more alienated light, describing her as “a loner” who garnered “little truck with the chummy folk fraternity” even as she took her place among the “cream of the urban folk revivalists.” [5]

A perception of Sainte-Marie that marked her as “different” speaks to her relationship to convention and how her time in New York shaped her approach to art and activism. [6] Arriving in Greenwich Village at the height of the 1960s folk revival, Sainte-Marie’s prolific songwriting – at once politically outspoken and creatively rich – reflected the racially diverse, youth-led, rebellious, and intellectually vibrant subculture that dominated the neighborhood’s cafés where espresso, music, and political discussion flowed freely. [7] The postwar folk revival rested on a Village legacy of social tolerance dating back to at least the 1890s, when members of a predominately Italian and Eastern European Jewish working-class neighborhood lived side-by-side with poor artists, gay and lesbian neighbors, political radicals, and Beat poets. [8] This legacy notwithstanding, by the 1960s Village performance venues witnessed at least as many creative and commercial gatekeepers as they did cultural and political nonconformists. Narrowly defined concepts of “authentic” folk singing discouraged artists from innovating outside of an established acoustic norm and predominately male café and club owners kept women artists from sharing bills with men while expecting them to tolerate harassment as a precondition of career success. [9]

Even as the Village proved a less inclusive environment than its outward appearance suggested, Buffy Sainte-Marie effectively harnessed the resources available to her as an up-and-coming artist in the heart of the national folk scene in order to craft a stage persona that resisted gender and race-based stereotypes, garner and maintain creative and commercial success, and use her popularity to raise awareness of dire needs among Indigenous communities across North America in an era of racial reckoning and social change. By making the most of her time in New York – an experience marked by the artist’s fascination with the rock and rhythm and blues shows of 1950s Brooklyn as much as the Village performances of the 1960s folk era – cultivating allies among fellow artists, and supporting Indigenous causes, Buffy Sainte-Marie charted a rare path forward as an influential artist and activist whose story paints a complex portrait of New York’s folk revival and the creative influences, cultural locations, and power brokers that shaped it.

Buffy Sainte-Marie, Authenticity, and the Folk Revival’s Politics of Style

Narratives of the folk revival suggest that for folk fans, typically White college students who viewed the postwar age of optimism with suspicion, making music in the folk idiom became an important form of “self-expression” and “cultural rebellion.” [10] But unlike other forms of rebellion that bookended the revival – from the Beats to the hippie counterculture – historian Grace Hale explains that “the folk-loving kids of the fifties and sixties turned to fantasies about the past to find their way.” [11] Searching for the “emotional truth” in music that brought together youthful outsiders attempting to restore the “parent generation” to a romanticized era that somehow preceded the injustices brought to light by the civil rights movement and carried out by military-industrial complex, many folk musicians adopted a stage image that involved what Judy Collins has called a “metamorphosis.” [12] For women, a pared-down appearance, barefoot and makeup free, or being pictured in “a long dress in a patch of weeds,” according to Collins, dominated. [13]

Ironically, this highly curated, and notably gendered, image of the “authentic folksinger” was as much a result of the artists’ proximity to New York-based recording companies as it was their genuine attraction to a romanticized view of the past. [14] It was Jac Holzman, the founder of Collins’s Village-based recording company, Elektra, that decided she looked like “definitely a product of the West” and that the studio would market her as such. [15] Reflecting on her experience, Sainte-Marie recalls the “business people” suggesting that she “appear in a powwow costume” as recording executives attempted to exoticize, and thereby profit from, her Indigenous heritage. [16] “It was about buy and sell,” recalled Sainte-Marie, explaining in a biography that her producer at Vanguard, Maynard Solomon, was “editing” much more than “producing” her. [17] Along the way, he reinforced the company’s perception of the artist as not only someone whose ethnicity Vanguard could caricature, but as drug-addicted and an anticipated “casualty” of the era’s increasingly liberal drug use among young people. [18] The nonconformity in Sainte-Marie’s choice of musical topics (her 1964 song “Cod’ine,” for example, discussed her experience with opioid withdrawal after a run-in with a criminal physician who wrongly prescribed her the drug) and her refusal to appeal to what historian Sherry Smith has called “superficial images” of “Indianness” that captured American imaginations at midcentury upset industry executives. [19] They found the depth that her music brought to Indigenous experiences “obscure” and – in the earthy parlance of one New York executive who worried about the music’s seemingly radical tinge – likely to open a “canna worms.” [20] At first distributing her records only to the nation’s coasts, Sainte-Marie paid a professional price for not complying with industry-manufactured notions of folk authenticity. [21] These challenges notwithstanding, a closer look at Buffy Sainte-Marie’s experience in the city complicates the constraints on women folk singers’ public images while underscoring why their stylistic choices were so important.

Buffy Sainte-Marie performs in her characteristic early 1960s look. Courtesy of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

Sainte-Marie flouted conventions established by industry executives and the folk commentariat. At the high noon of the revival in the early 1960s, widely read forums for folk music fans like Sing Out! magazine contained heated debates about the meaning of folk authenticity. [22] There, authors traded opposing views on folk singers’ obligation to authenticity in matters that ranged from their choice of instrumentation to their politics. [23] Folk purist Dan Armstrong, for example, groused in a 1963 Sing Out! piece about commercialized folk singers like the Kingston Trio whose music, he said, added to the “safe,” “prettied up,” and “watered down” themes of the nation’s uptick in low brow “instant culture” as they abandoned the regional sounds and Great Depression-inspired radicalism of folk heroes like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger for commercial gain. [24] In contrast to Armstrong’s perspective, rather than selling out, Sainte-Marie saw in show business an opportunity for self-invention and cultural experimentation.

According to Sainte-Marie, “part of what I loved most” about performing “was something the folkies hated: I loved the showbiz part! So did New Yorkers!” [25] In reference to her personal style and presentation, “I was a nerd but I dressed out of the Frederick’s catalog,” says Buffy Sainte-Marie, referring to the unapologetically stylish and urbane midcentury women’s clothing catalog, Frederick’s of Hollywood, whose models were more Diana Ross or Marilyn Monroe than Joan Baez or Judy Collins. [26] The artist goes on: “To folkies this was kinda suspect. But I wasn’t the plain-Jane type. I thought that was boring. I definitely got some eye rolling from folkies; but New Yorkers loved it. A little glamor didn’t scare them.” [27]

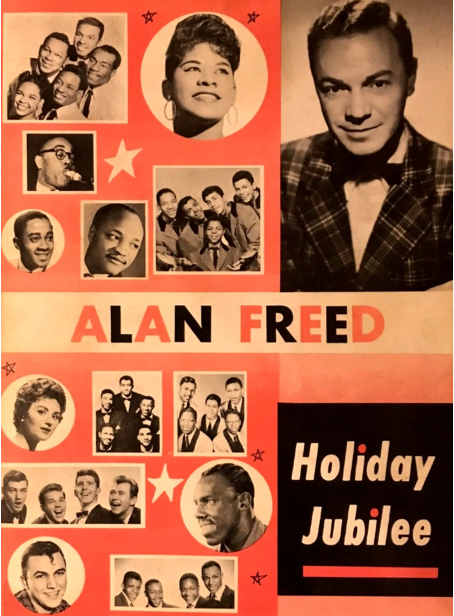

Advertisement for an Alan Freed rock and roll show at the Paramount. The Platters are pictured on the top left. Courtesy of the Alan Freed Chronological History in Newsprint online archive.

Reflecting on a relationship with New York neighborhoods and performance venues that predated her folk era success, Sainte-Marie recalls boarding a train from her childhood home in Maine throughout the 1950s to attend “Alan Freed rock ‘n roll shows” in downtown Brooklyn’s Paramount theater. [28] Before it closed in 1962, the Paramount under disc jockey Alan Freed’s direction featured several daring rhythm-and-blues (marketed under the more race neutral “rock and roll” genre) acts like The Platters, an all-African American quintet that flouted gender conventions by featuring Zola Taylor as the group’s female member and headliner. [29] Taylor performed in long, luxurious cocktail dresses and – nearly unheard of at midcentury – accompanied by four male backup singers. [30] The Platters’ performances captivated a young Sainte-Marie, as did rockabilly pioneer Jo Ann Campell, whom the artist describes as “gorgeous in a dress with a train, doing very hot music.” [31] Thinking back to the time she spent traveling back and forth to New York, years before her folk debut, Sainte-Marie asserts the rhythm and blues roots of the sound and performance image she would later establish for herself. In reference to the shows she saw at the Paramount, “that’s what changed my life,” says Sainte-Marie, “not Woody Guthrie.” [32]

Embracing the glamor of the acts she admired in her teens, when Buffy Sainte-Marie became a part of Greenwich Village’s 1960s folk scene, she defied the pressure to conform her look to a well-defined folk style, a pressure that was especially acute for women. Folk singer Alix Dobkin described how Elmer Gordon, her performance coach, insisted that she pile on layers of cosmetics before going on stage each night, attempting “to project the oxymoronic image of a sexy but urbane folkie.” [33] So to cast off heels, bouffants, and crinolines – and “be hugely successful anyway” – in the words of cultural critic Susan Douglas, became the mark of women folk singers who abandoned these style conventions as they delved into “dangerous and disruptive oppositional politics.” [34] Joan Baez, who adopted a simple mode of dress – frequenting stages make-up free with long, unteased hair, loose dresses, and barefoot – became the trendsetter in this space and women who to varying degrees followed in her unclad footsteps (like her sister Mimi Baez-Fariña and Judy Collins) curried favor with peers and executives. [35]

For Sainte-Marie, however, her glamor was not constricting or dictated by industry men. For the artist, dressing up, and dressing as she wanted, “far away from show business,” became a critical expression of agency as a young artist and an Indigenous woman in a world that she describes as “definitely an uneven playing field.” [36] Sainte-Marie’s appeal to glamor was, at least in part, not unlike the R&B singers of her youth who donned “knee-length skirts,” “high, teased hair” and “heavy makeup” to form a “glamorous city image” that established them as ultra-respectable in a society that typically denied that privilege to African American women. [37] As an Indigenous woman, in 1971, interviewer Sandra Shevey reported that ongoing pressure to dress “in fringe and feathers” ultimately “reaffirmed Buffy’s pride in her Indian heritage, and prompted her to write ‘Now that the Buffalo’s Gone”” and ‘My Country ‘Tis of Thy People You’re Dying’” – two tracks from her early records that introduced American history from an Indigenous perspective – to an audience beyond far beyond the Indigenous reservations whose point-of-view she represented. [38]

Buffy Sainte-Marie, Folk’s R&B Roots, and the New York Folk Festival

While managers exclaimed that “they didn’t know how to sell” Sainte-Marie and indicated that there was “no money” in her refusal to comply with their marketing plans, the success of Sainte-Marie’s early career undermined their complaints. Her aptly titled first album, It’s My Way (1964), resulted in a Billboard survey naming her “Best Female Folk Singer of 1964,” a designation that theater producer Manheim Fox used repeatedly to advertise her as a leading performer in the 1965 New York Folk Festival at Carnegie Hall. [39]

Attracting a different ensemble of artists than the citybillies who by this time usually populated major folk billings (Variety reported that “missing were such names as Joan Baez, Bob Dylan and Peter, Paul and Mary”), the New York Folk Festival instead featured artists who built their careers as 1950s rockabilly performers, including Chuck Berry and Johnny Cash. [40] Attended by an audience of over seventeen thousand, “mostly teenagers,” press reviews commented on the “freshness” and “novelty” that the performers brought to familiar material. [41] Although participants paid homage to poet and folksong anthologist Carl Sandburg (a cultural authority for folk purists) on the final day of the multi-day program, the event mostly stood out to reviewers for incorporating plenty of “big beat” music. [42] New York Times critic Robert Shelton observed that in place of “the customary sound of banjos or ballads” that one usually hears at folk concerts, Carnegie Hall was a “go-go” with the percussive sounds of swing, jazz, and rhythm and blues. [43] Days later, Shelton reported on the event’s notable “range” in which “square dances” were joined by “electrified rock and roll” and, in an apparent reference to Sainte-Marie’s song “Cod’ine,” “a protest song about narcotics addiction.” [44] Festival organizer Manheim “Manny” Fox named Sainte-Marie as his inspiration for the festival and, placing the folk revival’s seldom-acknowledged rock and rhythm and blues influences at the center of the program, introduced an alternative take on the revival and the musical influences that shaped it– influences more aligned with Sainte-Marie’s inspirations and artistic approach. A less well-documented event in folk revival history, Sainte-Marie’s participation in the New York Folk Festival suggests that diverse city venues provided a cultural haven for the artist who often performed for fans beyond the social, business, and stylistic constraints of the clubs in the Village.

Advertisement for Buffy Sainte-Marie’s appearance at the 1965 New York Folk Festival. Courtesy of the Carnegie Hall Archives.

It’s for this reason that Sainte-Marie saw New York as a unique place to break out of the mold of the quintessential female folk musician. She states: “I always felt totally free to have fun and push it onstage in New York. Audiences are just more experienced, more diversely exposed to variety, more curious, and more sophisticated in New York.” [45] There, she says, she felt less pressure to be “settler-oriented – like the American Songbook.” [46] This haven, in turn, made it possible for Sainte-Marie to become a trendsetting role model – someone who not only appealed to the college students who formed a “large, devoted, almost cultish following” but who inspired up-and-coming women artists, like Joni Mitchell. [47] Mitchell remembered that Sainte-Marie’s “songs were so smart, so well-crafted, and her performances were stunning” while adding that “she was different from the stereotypical industry old boys’ club . . . you could say I followed in Buffy’s footsteps.” [48]

When the Business of Folk Music is Business – Making It and Holding onto Success

Despite its public image of innocence and moral purity, the folk revival was plagued by sexism, and stories abound of aspiring folksingers, especially women, who found themselves taken advantage of in more than one way. [49] Alix Dobkin has described the “unwritten law of ‘no-two-chick-singers-back-to-back’” that limited women’s appearances on folk stages while sharing the unvarnished truth that “down to the marrow of our bones, every one of us [women folksingers] understood that a strong woman had better make it immediately clear that she was sexually available to men” and that “‘the important people’ in the audience were the men.” [50] Buffy Sainte-Marie discovered the male-dominated “showbiz capitalists” of the folk era to be “bullies and thieves” while encountering social and professional exclusion among fellow artists. [51] Her very presence as a seasoned musician and educated Indigenous woman seemed to break unspoken rules. [52] While this environment presented an implicit hierarchy that proved challenging to navigate, the artist nevertheless emerged from her time in New York with key allies. Her experience therefore points to the critical value of allyship for new artists.

Buffy Sainte-Marie speaks candidly about one of the more well-documented instances of professional abuse to which she was subject as an up-and-coming artist in the Village. Biographer Andrea Warner tells the story of an ill-fated night at the Gaslight when Sainte-Marie unwittingly signed away the rights to her antiwar song “Universal Soldier” to music supervisor Elmer Gordon. [53] She regained the rights for $25,000 a decade later. [54] “Part of ‘getting took,’” Sainte-Marie asserts, “was my own naivete. I wasn’t raised in a business family.” [55] But she also describes what it was like for a woman, socialized according to midcentury gender norms, to respond to myriad offers from executives who assumed that “exploitation was [to be] expected.” [56] “The feeling,” Sainte-Marie recalls, “was that you were outgunned and outnumbered . . . and my accommodation was to polite my way through it.” She continued: “I had . . . learned how to be a polite, good girl who could go to a record company and say ‘oh, where do I sign?’” [57] After such exchanges, Sainte-Marie remembered that “I would have a definite feeling that I had done the best I could under the circumstances . . . I had no idea that I had been exploited in any way.” [58]

It wasn’t only the executives that undermined the artist’s capacity to reap the rewards of her creative output or her access to professionally relevant opportunities. Sainte-Marie also reports on opportunities she missed out on from not quite fitting into the folk revival’s social circuit. As an unattached woman in a setting where women gained status as girlfriends and as an educated person who had cultivated her talent for years in college prior to arriving in New York, Sainte-Marie suggests some degree of insecurity if not umbrage that she inspired among the men in the Village. [59] Everyday social exclusion meant that “I missed a lot of inside information,” she says, since it was during “after-show fun where the networking and business deals blossom.” [60]

These disadvantages notwithstanding, Buffy Sainte-Marie acknowledges the pivotal role that allies played in advocating for her work. “Bob Dylan always stuck up for me,” says Sainte-Marie, adding that “Phil Ochs,” too, “and Richie Havens were real nice to me as a fellow writer. Odetta . . . and Len Chandler, who were two of the few people of color to achieve prominence in the Village,” also promoted Sainte-Marie at the start of her career alongside jazz connections she made at the Village Gate and the Bitter End. These include Cannonball Adderly, Nina Simone, Charles Lloyd, and Chet Atkins. So great were these influences, in fact, that Sainte-Marie came close to signing with the jazz label Blue Note before opting instead for classical-turned-folk outfit Vanguard. [61] Moreover, personalities with television shows, including Merv Griffin and Harry Belafonte, provided Sainte-Marie with a platform to “extend the content of my song explanations into celebrity chat, and inform the public,” especially about contemporary Indigenous experiences and concerns. [62] Such allies played a crucial role in Sainte-Marie’s career growth and supported the artist as she carved her own path in a context where compliance and conformity, rather than independence and individuality – especially for women – sometimes reaped the highest dividends.

Buffy Sainte-Marie and Indigenous Rights: Folk Music as Education

Historians of the folk revival describe how a yearning for “authenticity” among folk musicians in the early 1960s was intimately bound up with racialized expressions of “emotional ventriloquism” as they imitated, and appropriated, how Americans at the nation’s margins responded to everyday challenges through musical expression. [63] According to historian Grace Hale, when White rock and roll artists like Carl Perkins and Elvis Presley impersonated Black rhythm and blues singers, they were performing emotional ventriloquism, as did folk musicians like Dave Von Ronk whose early repertoire consisted of “Cajun, blues, and jug band music” recorded earlier by Black artists like Reverend Gary Davis and Mississippi John Hurt. [64] This “romantic fantasy,” Hale explains, had racist implications as White performers who mimicked the vocal inflections, performance gait, and emotional expression of African Americans from Southern regions “drew from the performance conventions of minstrelsy.” [65] For Buffy Sainte-Marie, however, folk music’s importance was not about imagining or embodying a “folk” abstraction. [66] Instead, she felt that the folk revival enabled her, through music, to educate audiences on the lived experiences – and ongoing injustices – known to Indigenous tribes throughout North America. [67]

During the folk era, Buffy Sainte-Marie used her songwriting to educate New York-based audiences on ongoing dilemmas faced by Indigenous tribes. Writing original songs at a time when critics lauded the prowess of male writers in the folk idiom like Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, and Tom Paxton, but rarely acknowledged women’s songwriting abilities until the emergence of the singer-songwriter trend in the early 1970s, it’s worth noting that Sainte-Marie was an active composer with over 200 songs to her name by 1963. [68] Reflecting on her music as an educational tool, she points to her performances of a song included in her first album, “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone,” that depicts the federal government as eager to carry forward a well-documented pattern of colonizing native land for economic gain – including when it commissioned the Kinzua Dam on the border of New York and Pennsylvania. Originating in the New Deal and completing construction in 1965, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the Kinzua Dam ostensibly to control flooding along the Allegheny River but with the net effect of creating jobs and providing electric power – all at the expense of local Senecas when the project condemned ten thousand acres of the tribe’s Allegheny territory. [69] Sainte-Marie remembers how audiences responded to her broaching this issue during sets:

“When I sang ‘Now that the Buffalo’s Gone’ to intelligent New York audiences, it was the first time they had heard about the building of Kinzua Dam in . . . their own state . . . To build the Kinzua Dam, Congress unilaterally broke the oldest treaty in Congressional archives, written during the time of George Washington. They flooded and evicted the Seneca Nation from their reservation – in New York. I thought that if audiences only knew about Indigenous exploitation they’d help. But what was the most common New York reaction to my song about Kinzua Dam? New Yorkers said politely, ‘Aw, the little Indian girl must be mistaken.’ So that’s what we were facing.” [70]

While New York audiences failed to embrace the urgency of Sainte-Marie’s message, Alix Dobkin recalls that she joined other Indigenous songwriters in the folk revival, including Patrick Sky and Peter LaFarge, in “earn[ing] wide respect for bringing to the scene a consciousness of the original American genocide and continuing oppression of their people, as well as a passion for their heritage.” [71] The platform she built in the revival enabled her to support Indigenous causes in more comprehensive ways subsequently. By the end of the 1960s, Sainte-Marie had set up a scholarship fund for Indigenous students, offered benefit concerts to support organizations such as the American Indian Movement (AIM) and the Indians of All Tribes, and pushed effectively for major television networks to hire Indigenous talent to play Native American characters (the latter accomplishment much against the wishes of her complacent business managers in New York). [72] Although in New Yorkers the artist at first found a limited audience for the Indigenous rights education her music provided, eventually her performance activism laid a crucial foundation from which later efforts emerged – and remain in motion today. [73]

New York City as Inspiration and Steppingstone

Buffy Sainte-Marie’s experience in the city was a formative stop on a longer journey whose dimensions became global in scale. The artist’s experiences in early 1960s New York provide new insights that compliment and expand the historical record on the folk revival. They highlight the impact of musical trends like rhythm and blues and rock and roll on folk music, add dimension to the revival’s politics of style, shed light on women’s experiences building careers and forming networks, and complicate the revival’s proximity to race relations and reform efforts – including for Indigenous rights. The era’s complexities notwithstanding, Buffy Sainte-Marie best captures the city’s flavor and vitality that shaped her artistic development during the folk revival: “I always had the feeling that my big dreams elsewhere were not at all too big in New York. That the city could accommodate anything I dreamed up. If some of my songs were . . . not folkie enough for the Village folk purists, no problem at all: just go up town a little and there’s an audience for just about everything. It’s that capacity that thrills me about New York.” [74]

Christine Kelly teaches American History courses at Fordham University where she completed her PhD in History in 2019. She previously served in student support offices at Fordham University and Johns Hopkins University.

[1] Walter C. Meyer, “Like No Other Folksinger – That’s Buffy Sainte-Marie: It’s Her Way,” New York Sunday News, February 26, 1967, 6, Native American Biography Vertical File (ca. 1850-2000), Collection No. 9242, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Series I. Native American Individuals, Box 3, Folder Sainte-Marie, Buffy (henceforth Cornell NABVF).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Barbara Hogan, “The Cree with a Kink in Her Voice,” Look, December 15, 1964, 59, M-Clippings, Sainte-Marie, Buffy, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (henceforth NYPL Performing Arts).

[4] “Spotlight! Record Reviews,” June, 1965, clipping, Carnegie Hall Archives, New York, New York; “Sainte-Marie, Buffy,” Current Biography, July 1969, 40, NYPL Performing Arts.[5] “Folk Singers: Solitary Indian,” Time, December 10, 1965, 62, M-Clippings, Sainte-Marie, Buffy, NYPL Performing Arts; Dick Weissman, Which Side Are You On?: An Inside History of the Folk Music Revival in America (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006), 166.

[6] “Sainte-Marie, Buffy,” Current Biography, July 1969, 39, NYPL Performing Arts.[7] Justin Sablich, “From Macdougal Street to ‘The Bitter End,’ Exploring Bob Dylan’s New York,” New York Times, October 18, 2016, sec. Travel, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/18/travel/exploring-bob-dylans-greenwich-village-new-york.html; Stephen Petrus and Ronald D. Cohen, Folk City: New York and the American Folk Music Revival (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 163.

[8] Gillian Mitchell, The North American Folk Music Revival: Nation and Identity in the United States and Canada, 1945–1980, New Edition (Burlington, VT: Routledge, 2016), 114; Petrus and Cohen, Folk City, 151.

[9] On folk purists who defined and defended “authentic” folk singing during the revival era, see Rachel C. Donaldson, “I Hear America Singing:” Folk Music and National Identity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014), 140 – 142; Alix Dobkin, My Red Blood: A Memoir of Growing Up Communist, Coming Onto the Greenwich Village Folk Scene, and Coming Out in the Feminist Movement (New York: Alyson Books, 2009), 170 – 171; Buffy Sainte-Marie, in conversation with author, May 12, 2023.

[10] Grace Elizabeth Hale, A Nation of Outsiders: How the White Middle Class Fell in Love with Rebellion in Postwar America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 100.

[11] Ibid., 99.

[12] Hale, A Nation of Outsiders, 95; Robert Cantwell, “When We Were Good: Class and Culture in the Folk Revival,” in Neil V. Rosenberg, ed., Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993),50; Judy Collins, Sweet Judy Blue Eyes: My Life in Music, Reprint Edition (New York: Three Rivers Press, 2012), 64.

[13] Cantwell, When We Were Good, 337, 379; Robin Herman, “Two 60’s Songbirds in the Park: Two 60’s Songbirds In Central Park Spotlight Attacked From Left and Right; Tips on Tickets ‘The Right to Make the Choices’ Holography Show in Southampton,” New York Times, July 6, 1979, sec. The Weekend, C1.

[14] Petrus and Cohen, Folk City, 81; Mick Houghton, Becoming Elektra: The True Story of Jac Holzman’s Visionary Record Label (London: Jawbone Press, 2010), 92.

[15] Mark Abramson qtd. in Collins, Sweet, 83 – 84.

[16] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[17] Andrea Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie: The Authorized Biography (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2018), 64.

[18] Buffy Sainte-Marie, in conversation with author, May 12, 2023; Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie, 64.

[19] Sherry Smith, “Indians, the Counterculture, and the New Left,” in Daniel Cobb and Loretta Fowler, eds., Beyond Red Power: American Indian Politics and Activism Since 1900 (Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research, 2007), 144.

[20] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[21] Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie, 66 – 67.

[22] Donaldson, “I Hear America Singing,” 132 – 133.

[23] Stephen Fiott, “In Defense of Commercial Folksingers,” Sing Out!, Dec.-Jan., 1962, 43, Tamiment Library and Wagner Labor Archives, New York University, New York, New York.; Dan Armstrong, “‘Commercial’ Folksongs – Product of ‘Instant Culture,’” Sing Out!, Feb. – Mar. 1963, 20.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Marc Myers, Rock Concert: An Oral History as Told by the Artists, Backstage Insiders, and Fans Who Were There (New York: Grove Press, 2021), accessed via Google Books; Andrew Glazer, “Singer Zola Taylor Broke Gender Barriers in the 1950s as a Member of The Platters,” Chron, May 6, 2007, https://www.chron.com/news/houston-deaths/article/singer-zola-taylor-broke-gender-barriers-in-the-1599906.php.

[30] Beth Fowler, Rock and Roll, Desegregation Movements, and Racism in the Post-Civil Rights Era (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2022), 97; “Platters Make Chicago Night Club Debut, Held Over,” Jet, June 1, 1967, vol. 23, no. 8, 56.

[31] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Alix Dobkin, My Red Blood, 173.

[34] Susan J. Douglas, Where the Girls Are: Growing Up Female with the Mass Media, Reprint Edition (New York: Three Rivers Press, 1995), 145, 147.

[35] David Hajdu, Positively 4th Street: The Lives and Times of Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Mimi Baez Fariña, and Richard Fariña, 10th Anniversary Edition (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011), 62 – 63; Douglas, Where the Girls Are, 146.

[36] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[37] John Clemente, Girl Groups: Fabulous Females Who Rocked the World (Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse, 2013), 402; Mark Naison, “Girl Groups in the Bronx: Race, Gender and the Pursuit of Respectability,” Occasional Essays: Bronx African American History Project, 3 (2019): https://research.library.fordham.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1002&context=baahp_essays.

[38] Sandra Shevey, “Buffy Sainte-Marie: Righteous Indignation,” Ladies of Pop/Rock (New York: Scholastic, 1971), 29, 35, M-Clippings, Sainte-Marie, Buffy, NYPL Performing Arts.

[39] Advertisement for the New York Folk Festival, New York Post, June 1, 1965, clipping, Carnegie Hall Archives.

[40] “N.Y. Folk Festival in Solid Bow; 51G Take Despite Name Shortage,” Variety, June 23, 1963, Carnegie Hall Archives.

[41] Robert Shelton, “First Folk Festival Here Ends with Carl Sandburg’s ‘Songbag,’” New York Times, June 21, 1965, Carnegie Hall Archives; Robert Shelton, “Folk Event Opens with a “Big Beat,” New York Times, June 18, 1965, Carnegie Hall Archives.

[42] Robert Shelton, “Folk Event Opens with a “Big Beat,” New York Times.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Robert Shelton, “First Folk Festival Here Ends with Carl Sandburg’s ‘Songbag,’” New York Times.

[45] “Sainte-Marie, Buffy,” Indigenous Saskatchewan Encyclopedia, https://teaching.usask.ca/indigenoussk/import/sainte-marie_buffy_beverly_1941-.php; Advertisement for the New York Folk Festival, New York Post, June 1, 1965, clipping, Carnegie Hall Archives.

[46] Here, Sainte-Marie is referring to The American Songbag, a 1927 anthology of American folk songs compiled by poet, journalist, and biographer Carl Sandburg. The anthology’s song collection put forward an image of folk Americana that many aspiring folk singers adopted.

[47] Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie, 3; “Sainte-Marie, Buffy,” Current Biography, July 1969, 40, NYPL Performing Arts.

[48] Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie, 3.

[49] Cantwell, “When We Were Good,” in Rosenberg, Transforming Tradition, 58.

[50] Alix Dobkin, My Red Blood, 175.

[51] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie, 69.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Buffy Sainte-Marie, in conversation with author, May 12, 2023.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Buffy Sainte-Marie, in conversation with author, May 12, 2023; Suze Rotolo, A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties (New York: Broadway Books, 2009), 273.

[60] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Hale, A Nation of Outsiders, 102. See also Doug Rossinow, The Politics of Authenticity: Liberalism, Christianity, and the New Left in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), 4 – 5.

[64] “Artist Spotlight: Dave Van Ronk,” Smithsonian Folkways Recordings, https://folkways.si.edu/dave-van-ronk/american-folk-blues-gospel/music/article/Smithsonian; Dave Von Ronk with Elijah Wald, The Mayor of MacDougal Street: A Memoir (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2013), 136.

[65] Ibid.

[66] CineFocus Canada, Buffy Sainte-Marie: A Multimedia Life, 2006, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1nNbR791go&t=764s.

[67] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[68] Robert Shelton, “Old Music Taking On New Color: An Indian Girl Sings Her Compositions and Folk Songs; Blind Street Singer Moves Indoors for Stage Numbers Writes Impressive Songs Appears in Flowing Robes,” New York Times, August 17, 1963, 11, Buffy Sainte-Marie Vertical File, The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

[69] Maria Diaz-Gonzalez, “The Complicated History of the Kinzua Dam and How It Changed Life for the Seneca People,” Environmental Health News, January 30, 2020, https://www.ehn.org/seneca-nation-kinzua-dam-2644943791.html#:~:text=The%20formidable%20Kinzua%20Dam%2C%20which,Allegany%20Territory%20to%20the%20dam.

[70] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[71] Dobkin, My Red Blood, 154.

[72] “Nihewan Foundation History,” Nihewan Foundation, http://www.nihewan.org/history.html; Blair Sabol, “Buffy Sainte-Marie: Outside Fashion,” Village Voice, July 31, 1969, M-Clippings, Sainte-Marie, Buffy, NYPL Performing Arts; John Weisman, “Singer Buffy Sainte-Marie Crusades for Indian Rights,” Los Angeles Times, October 15, 1970, G30; Warner, Buffy Sainte-Marie, 154; Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.

[73] Stonechild, It’s My Way!, 163.

[74] Buffy Sainte-Marie, written account of folk revival in New York, e-mailed to author, May 12, 2023.