Building for Us: Stories of Homesteading and Cooperative Housing

REVIEWED BY KATIE UVA

New York City is in the throes of a housing crisis. Soaring housing costs and stagnant wages have left increasing numbers of New Yorkers rent-burdened, and have moved the possibility of homeownership even farther out of reach in a city that has always been dominated by renters. Pro-growth voices argue that rezoning and incentivizing private developers to do more building would open up supply and alleviate the crisis; progressives resist that narrative and see such ideas as furthering the city’s capitulation to the private sector and worsening the tension between housing as an asset versus housing as a right. Conflicts abound about how to create affordable housing, how to define affordable housing, and how to sustain affordable housing.

Building for Us: Stories of Homesteading and Cooperative Housing. Interference Archive. On view October 17, 2019-February 2, 2020.

Interference Archive’s current exhibition, Building for Us: Stories of Homesteading and Cooperative Housing, hearkens back to a drastically different moment in the city; it traces the development of self-help housing from its origins in the 1970s, when the legacies of redlining, suburbanization, and disinvestment converged to devastate low-income, predominantly Black and Latino neighborhoods in the city, through the present. The footage of burned out, abandoned or nearly abandoned buildings flanked by empty lots and rubble is familiar to anyone who studies New York in the 1970s or was there to see it themselves. But Interference Archive’s exhibition, alongside recent works like the documentary Decade of Fire, move beyond the images of destruction to reorient the story of New York in the 1970s toward one of New Yorkers tenaciously advocating for themselves and fighting to hold onto and revive their communities in the process. It also implicitly offers limited equity coops and self-help housing as an alternative to market-driven housing, a possibility worthy of greater support and expansion in the present-day city.

Building for Us begins by contextualizing the 1970s, with a map that plots limited equity coops onto a redlined map of the city. The map connects the legacy of redlining, which had been formally outlawed by the 1970s, with its lingering effects on the city. The exhibition helpfully emboldens key terms and also offers a one-page glossary for visitors to carry with them as they explore the artifacts, which includes contextual concepts like foreclosure, homesteading, redlining, and sweat equity. Oral histories from current HDFC tenants accompany the artifacts and interpretive text—one tenant recounts huddling around a single space heater with her neighbors in a building that was no longer being maintained by the landlord; another describes hugging a newly operational radiator after spending two years with no heat.

The tenant accounts make vivid the experience of being neglected by landlord and government alike in 1970s New York—this was the era when city leaders flirted with the idea of planned shrinkage, and the erosion of public services made it more profitable for landlords to commit arson and collect insurance on their buildings than to invest in repairs and maintenance. As the system broke down, grassroots organizations filled the void. The Urban Homesteading Assistance Board (UHAB), which partnered with Interference Archive on this exhibition, was created in 1973 under the aegis of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine to help support New Yorkers who wanted to take over abandoned buildings and become homeowners. Around the same time, local groups like the Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association, the 11th Street Movement, the Renigades of East Harlem, and Williamsburg’s Los Sures, among many others, were forming and organizing residents in distressed neighborhoods to clear out rubble and rehabilitate housing stock. Ultimately these groups would form a network that advocated for and generated thousands of units of housing; there are approximately 1,300 resident-controlled, low-income housing cooperatives in New York today, and the exhibition describes those units as “some of the most deeply affordable and stable housing in the city.”

UHAB and other self-help groups were energetic in mobilizing people and innovative in establishing sustainable frameworks for tenants to become owners; the exhibition is full of manuals and guides for residents on how to make repairs and how to organize themselves into functional associations. UHAB also took an active role in mediating between homesteaders, developers, and the city government. The Tenant Interim Lease Program (TIL), created in 1978, reflects the fruitfulness of UHAB’s nimble advocacy; the program converted nearly 1,000 buildings into HDFCs by the early 1980s.

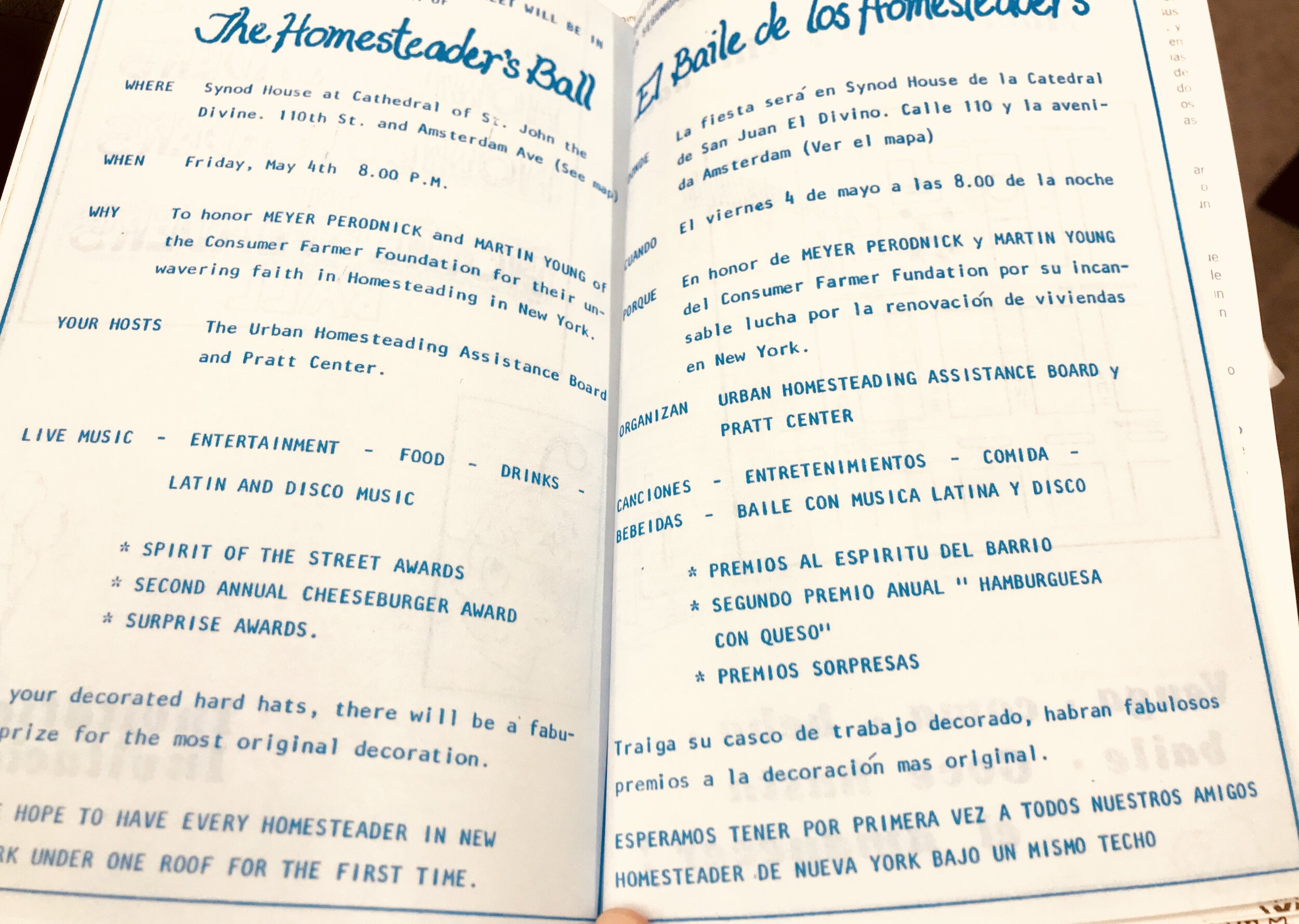

In addition to the legal frameworks that enabled tenants to become owners, the exhibition is rife with interesting artifacts that reflect the community-building aspects of self-help housing. A bilingual 1978 flier advertises the “Homesteader’s Ball,” with Latin and Disco music and a prize for most original hardhat decoration, while a cookbook created by HDFC residents celebrates the 20th anniversary of the TIL program. Detailed accounts of how specific HDFCs came into being highlight the tenacity of their residents; Nina Dunn HDFC in the Bronx completed TIL in 1986 after seven years of fighting to hold onto the building. Umbrella House on Avenue C emerged as a limited equity coop in 2012 after beginning as a collection of squats and performance space in a dilapidated building in the late 1980s. 105 St. Homesteaders demolished and rehabbed their buildings for 10 years while also resisting various attempts to repossess the buildings. A collective story emerges from these distinct examples—throughout the city, tenants banded together to preserve and improve their housing and lay claim to their neighborhoods. They saw value and community where lenders, government, and landlords saw decline and hopelessness.

UHAB event flier, 1978.

Cookbook with recipes from HDFC residents, 1998.

UHAB and many of the other organizations named in the exhibition continue to this day, but the nature of housing in the city has changed, and this raises interesting questions for how this history might be applied and adapted to the present crisis. Self-help housing thrived in a climate of abandonment and declining values, but could it be reshaped to preserve affordability in a city of excessive speculation and ever-increasing values? How might the city expand its commitment to community land trusts (CLTs) and HDFCs? How might the city become a more equitable place if tenants were empowered to lead the planning process? What role could HDFCs and CLTs play in a Green New Deal? How could a deeper commitment to self-help housing on the part of the city mitigate New York’s struggle with homelessness? There is no magic cure for the issues the city faces today, of course, but the legacy of self-help housing offers a confrontation with the current paradigm and some intriguing possibilities for a path forward.

Katie Uva is an editor at Gotham.