Cartooning the City: Roz Chast and Julia Wertz

Reviewed by Martin Lund

Going Into Town:

A Love Letter to New York

by Roz Chast

Bloomsbury USA (2017)

When I was asked by Gotham to review Roz Chast’s Going into Town: A Love Letter to New York and Julie Wertz’s Tenements, Towers & Trash: An Unconventional Illustrated History of New York City, I had no idea what to expect. Both writer-illustrators are known for tackling a wide variety of topics, albeit most commonly personal subjects. Both Chast and Wertz work in styles of art and storytelling that are readily identifiable, even as their work always delivers something new. With this in mind, all I knew for certain when I said yes to the request to review was that I would be getting two books of graphic arts that dealt with New York City, and that I would be able to tell who had done which book. Anything else, it seemed to me, was anybody’s guess. How the two would relate to each other was similarly up for grabs; they could be boringly similar or wildly different.

Tenements, Towers & Trash:

An Unconventional Illustrated

History of New York City

By Julia Wertz

Hachette/Black Dog & Leventhal (2017)

Having come out at the other end of the reading experience, unharmed but highly amused, I can report that I was simultaneously both right and wrong — Going into Town and Tenements, Towers & Trash are similar, but in ways that mark them as very different indeed from each other.

The differences start long before you get to the first page. Chast is a daughter of Brooklyn, and of parents who did not venture into "the City" too often and who rarely stayed for long when they did. It was only when she was a bit older that Chast began going into Manhattan on her own. That’s when she truly fell for the place, even though she stayed in Brooklyn. Eventually, she and her family had to leave the city for the suburbs, but she left a piece of her heart behind and she would later channel that piece in Going into Town. Wertz, on the other hand, is a Californian born and bred. She only moved to New York as an adult who had already done enough illustration and comics work to get off the ground. (When I first heard of Wertz, she was already living in New York, which was something that was remarked upon explicitly in that conversation; Wertz’s pre-NYC comic that was singled out that night, The Fart Party, was described as lacking a sense of place as opposed to Drinking at the Movies, a comic about Wertz’s life in New York — and about movie theaters in the city. Wertz herself describes Drinking at the Movies on her website as being “basically about what a fucking moron I was when I first moved to NYC.”)

So Chast’s a Brooklynite and Wertz is a Californian. Both have in common what they describe as an abiding love for New York City. Chast describes the city as “still the only place I’ve been where I feel, in some strange way, that I fit in. Or maybe, that it’s the place where I least feel that I don’t fit in.” Wertz emphasizes as a similar point: she never felt at home in the small northern Californian town she grew up in and, although San Francisco felt more like her scene, it wasn’t until she “discovered New York City when I felt like I found the place I was supposed to be. The frenzied, neurotic pace of the east coast felt comfortable and familiar, so I settled in.” In short, they both felt a sense of belonging in New York. And, having both left the city behind — one for reasons of family and the other because she fell victim to that insatiable beast, NYC real estate — they both felt a need to say their piece about the city. Both expressly note that they are sharing their own, idiosyncratic view of New York, but frame it differently: Wertz says that ultimately, she made Tenements, Towers and Trash for herself while Chast shared her city in the hope of turning others onto New York, so that they might come to love it as much as she does.

And so the differences start to multiply, while the similarities remain in plain sight. Chast’s Going into Town started off as a small booklet the author made for her daughter, when she left Suburbia (Chast’s capitalization) to attend college in Manhattan. It is not a guidebook, nor an “insider’s guide” or history book; it’s Chast telling readers why she loves New York (read: Manhattan) so that maybe, hopefully, others might come to love it too. It contains a very basic introduction to Manhattan — its placement relative to the other boroughs; the grid, the directions of streets (east-west) and avenues (north-south), and the chaos below 14th Street; that Broadway cuts diagonally across the island and that 5th Avenue divides the East Side from the West; and so on. This is followed by chapters on “Walking Around,” “The Subway,” “Stuff to Do,” and “Food,” to name a few. The end result is an ordered book, a clearly structured work that follows a set path through the big things to the small(ish).

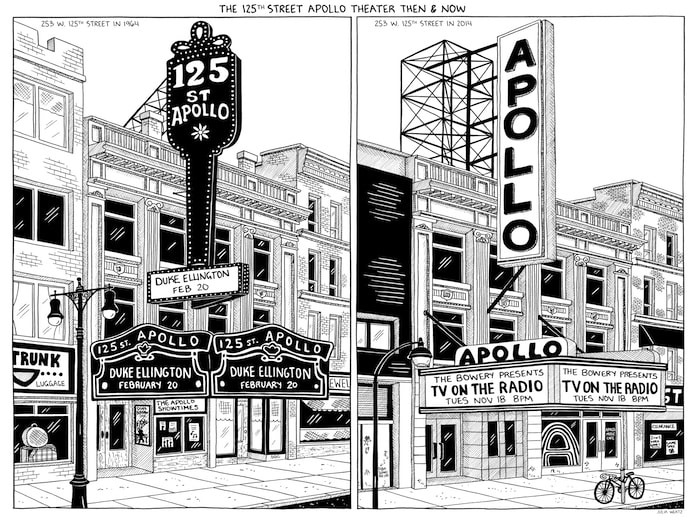

Wertz’s book, on the other hand, is a catalog of sorts, a collection of the obscure. Between its covers, buried in one or several of its nearly three hundred pages is bound to be a factoid to satisfy most tastes. Tenements, Towers & Trash is not, Wertz points out, a “typical” history book, not a useful guide to New York. Instead, it is described as a book about “unique and often forgotten stories from the city’s past, accompanied by illustrations of random neighborhoods as they were and as they are.” Tenements is undeniably a sprawling thing, seemingly unfocused and prone to jump from topic to topic as if dictated by nothing but the writer-illustrator’s whims. Take, for example, the story of “Madame Restell: The Despised Abolitionist of 5th Avenue” (66–67), which is lodged between a twelve-page “Biased Guide to New York’s Independent Bookstores” and two two-page spreads showing 1540 Broadway in 1915 and again in 2015. Lest the reader think I am complaining here, I hasten to add that this a statement of fact — the eclecticism of the works collected in Tenements is part of the volume’s charm, not knowing what awaits once the current vignette comes to an end.

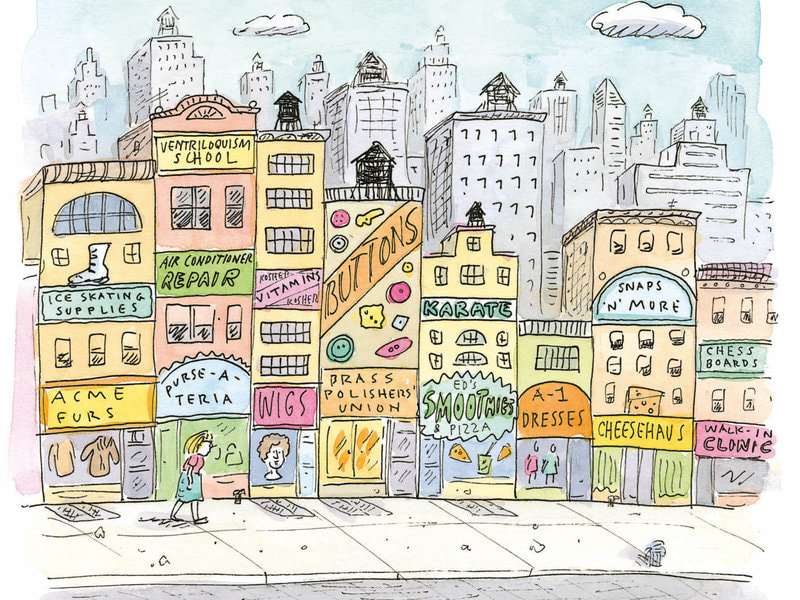

Ultimately, where the two volumes differ most clearly is in scope and ambition. The two writer-illustrators’ perspectives on the city, and the styles with which they share them, are as different as they could be, while still presenting books so similar to each other: both are mixes of text, cartoon, and photography. Chast’s work is over before you know it; it pulls you in and drags you along for the ride. The pages are open, full of air, and with plenty of space between lines of writing, panels and illustrations, and other elements of page composition. Wertz’s Tenements, Towers & Trash, on the other hand, requires you to stop, to survey the oversized pages, to take in and compare the details. The text is packed tight, most pages brimming with information. Further, Chast often treats the city in an impressionistic way, focusing on things she’s found on the street or in a shop window, or on creating amalgams of different storefronts and facades that the she fills with advertisements and signage that she has dreamed up herself to exemplify the semiotic craziness that marks so much of the city as a crazy-quilt of signs and symbols. Conversely, for the most part Wertz relishes in attempted verisimilitude: cartooning is an art of simplification, so the reader should not exact photorealism in Tenements, but she emphasizes architecture as it looks, more or less. If Chast’s New York streets are caricatures, Wertz’s are snapshots.

Both writer-illustrators position their works in similar areas without occupying anything like the same space. They reach this strange state with the help another writer famous for, among other things, publicizing his own views about the city. E. B. White wrote in his classic Here is New York that there are at least three New Yorks: the New York of the native, who takes it for granted; of the commuter, who devours it by day and abandons it at night; and of the person born elsewhere and comes to it in search of something. Chast quotes this triad at the end of her book, while Wertz’s book begins with the list as its epigraph. And yet, both authors prove White wrong, in a sense; there are far more than the three New Yorks White lists and his would-be heirs mention, and some of them appear in the portraits painted by our writer-illustrators.

Still, both books fall into the same broad subgenre, that of the former-NYC resident reminiscing over the city and, in most cases, what made them fall for the city and what they miss about it. I belong to that crowd of former New Yorkers — or of former New York residents, if someone out there would like to challenge my onetime New Yorkerness — but this review will not take a turn into this genre. I don’t love New York. I definitely don’t ♥ New York. To be perfectly frank, I don’t even like New York all that much. I don’t regret having lived there, but I also didn’t shed any tears when time came to leave. Unlike Wertz, I don’t keep “daydreaming about the city and scheming of ways to get back to it.”

Still, Chast’s book — a “love letter” to Manhattan — repeatedly brings a knowing smile to my face as I read some thing or other that is familiar. I recognize many of the situations she sketches, but I don’t share the sentiment behind the book, a sentiment Chast shares with so many others: “This is the best place in the world.” And Wertz’s factoids are fun to read, particularly for the many double takes they inspire. But in the end, she too seems to land in a similar New York exceptionalism. I cannot end this review without saying, by way of conclusion, that I undoubtedly find both books amusing. But they are also, at least to me, ultimately forgettable. As with so many of the city’s cheerleaders, Chast and Wertz paint a picture of New York that leaves little room for the reader to remember or perhaps even imagine that for many people, New York is not the best place, nor even a particularly good one.

Martin Lund is a former Visiting Research Scholar at The Gotham Center for New York City History and the most recent author of Re-Constructing the Man of Steel: Superman 1938–1941, Jewish American History, and the Invention of the Jewish–Comics Connection.