Dispatches from “Anthropoid Ellis Island”: New York City’s More-Than-Human History

By Barrie Blatchford

New York City’s status as entrepot for millions of new Americans is one of the most well-known aspects of American history. But much less understood is that the city has long been the epicenter of the American (nonhuman) animal trade, a shadowy and little-studied subject that was nevertheless of enormous importance and pecuniary value.[1] Indeed, as New York City welcomed millions of new human immigrants in the decades after the Civil War, the increased mobility of the era also facilitated a rapidly expanding trade in animals. The creatures swept up in this trade were destined for often-dismal fates in zoos, circuses, travelling road shows, medical research laboratories, and as exotic pets — provided they survived the arduous trip to America in the first place. The archival record of these creatures, and of the people who bought and sold them, is frustratingly scant and scattered. Nevertheless, traces do exist that allow for the story to be excavated in part. This essay thus takes a first step towards a multi-species history of immigration to New York City via an exploration of the lives and business dealings of two men long at the forefront of New York’s animal trade: Charles Reiche and Henry Trefflich.[2]

Of course, animals have long circulated, often unbeknownst and undesired, in the wake of the movement of people, a process greatly accelerated by European colonization. Following 1492, numerous European-Asiatic animal species became established in North America, ranging from domestic fodder animals to unwanted organisms like rats. Some ventured the other way, too, but the bulk of the species transfer was from Europe to North America.[3] By the 19th century, though, animal migration had entered a new phase, one much more purposeful and animated by exhibition, not agriculture. The rise of zoos, private menageries, and circuses sparked demand, and the dramatic expansion of European (and American) empires combined with the enhanced speed and capacity of ships facilitated supply. By the latter third of the century, substantial private animal dealers had emerged to capitalize on the demand for exotic animals — most famously, the German Carl Hagenbeck, who was well-known in America too. Yet Hagenbeck’s immense worldwide network was once rivalled by that of the Reiche brothers, whose contemporary prominence has long since sunk into unjust obscurity.[4]

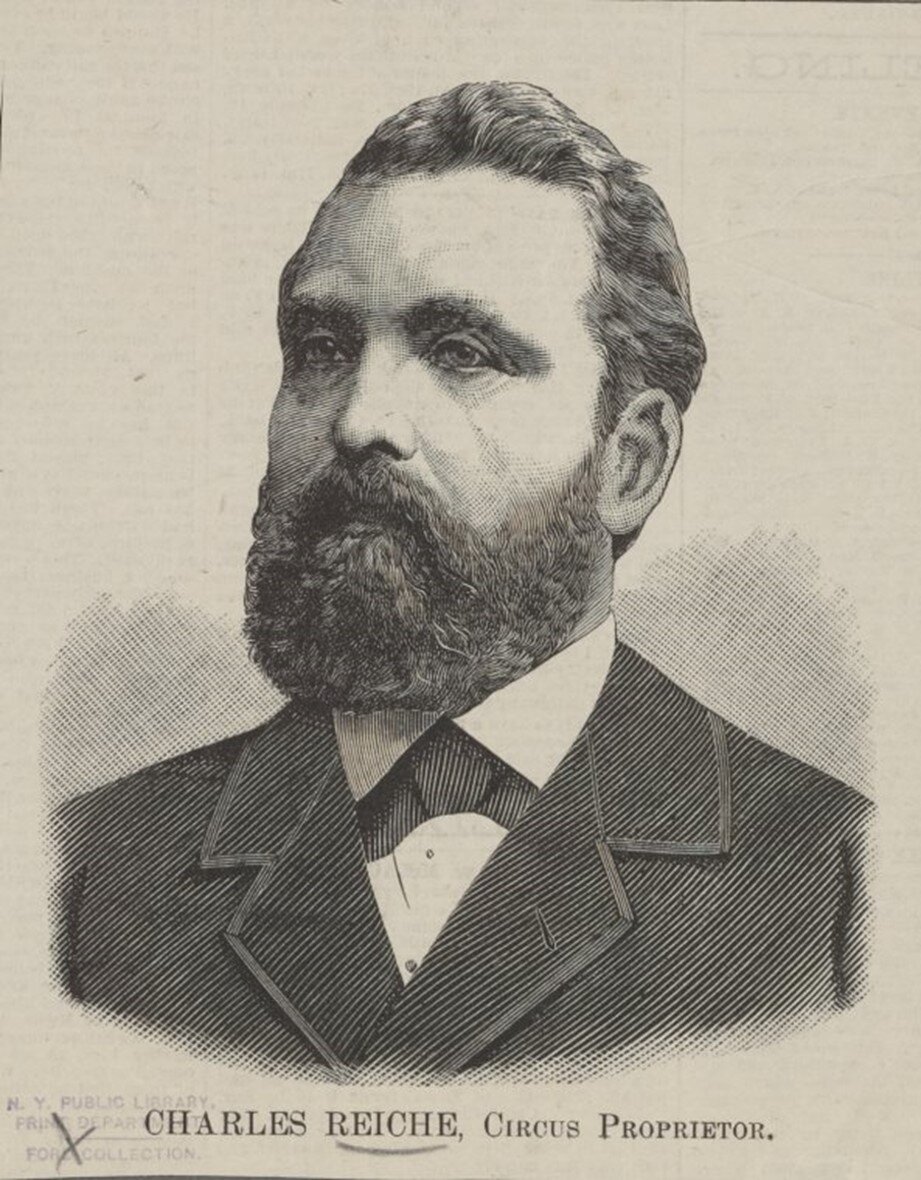

An Image Likely, Though Not Definitely, of Charles Reiche. “Charles Reiche, Circus Proprietor.” Undated, though probably from the 1870s or 1880s. Photo Courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library.

Charles Reiche and his younger brother Henry emigrated from Germany to America sometime around 1840. Like many things to do with the Reiches, exact details are fuzzy. But one thing we know is that they soon began a successful business — Charles Reiche & Brother — in New York City selling birds imported from around the world. As early as 1853, Charles claimed to have sold 20,000 birds since the founding of his business, a tally that associates contended had risen to around 500,000 by 1875.[5] Later commentators even asserted that the Reiche brothers were the first to import canaries in any quantity into America, and had a hand in one of the first introductions of the English sparrow.[6] Under Charles’s apparent leadership in America, the Reiches expanded from birds to all manner of creatures — snakes, lions, elephants, tigers, and more — and opened branch offices in Boston and Chicago by the 1870s.[7] By that point, Charles Reiche had become an animal dealer of such magnitude that his only real rival was the famed Carl Hagenbeck. Like Hagenbeck, Reiche’s business spanned the globe and was predicated upon colonialism. Reiche’s business particularly relied upon collectors in East Africa — comprised of European adventurers and African laborers — who captured creatures that were then shipped to Germany, where Henry Reiche often presided.[8] Soon the animals made their way across the Atlantic, doubtless with terrible attrition at every point of this convoluted journey, to dock in New York City.

Coup & Reiche New York Aquarium Building. Photo Courtesy of the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library, 1876.

Charles Reiche maintained an office in Manhattan, but eventually stored most of his stock at a stable he had built across the Hudson in Hoboken, New Jersey, where he also had a handsome residence. Reiche’s prominence in New York grew alongside his pocketbook, which by the 1870s was bulging. Though comprehensive data on Reiche’s capital do not exist, he told a journalist in 1874 that he was importing between $200,000 and $300,000 worth of birds in a given year — and that the annual bird traffic through New York City amounted to some $1,000,000 per year.[9] Three years later, a newspaper article reported Reiche’s net worth at over $1,000,000.[10] Whatever the precise figures, Reiche’s local eminence was growing too. He made headlines by successfully challenging the federal government’s animal import tax policy before the Supreme Court in 1871.[11] In 1876, Reiche’s metropolitan influence waxed still further when he became one of the driving forces behind the advent of the New York Aquarium. The Aquarium, erected at 35th Street and Broadway, brought all manner of fish and marine mammals to the city via the Reiche acquisition network — it even featured elephants at one point.[12] Nevertheless, in spite of early popularity, the Aquarium folded in 1881 due to repeated management squabbles. However, it remains a testament to Reiche’s significance and the vast reach of his business.[13]

Reiche’s imports continued to captivate the public imagination even after the Aquarium years, though, especially as they grew more audacious and mammalian. Reports consistently mention throngs of children and curiosity-seekers trailing the newest batches of animals from disembarkation to their temporary destination at 10th and Hudson Streets in Hoboken. Indeed, “large crowds” and “gentlemen” received the 1884 arrival of Reiche’s alleged “mammoths” — which were surely elephants, though Reiche had whipped up interest by claiming his collectors had found living woolly mammoths in Malaysia.[14] But even without such hype, “hundreds of shouting children” followed the baby African elephants Jack and Mary — and an assortment of leopards, hippopotami, lions, and others — to the Hoboken stables in 1882.[15] Even an 1882 elephant sale at the stable — for $6,600 — warranted blow-by-blow coverage in The New York Times, an article which also revealed the dismal treatment of the captive pachyderm: the unnamed elephant was “poked” by Reiche with a cane, and “hooked by one of his blanket-like ears” in order to be brought outside.[16]

But headlines as well as sales dwindled sharply after Charles Reiche’s 1885 death and that of his brother Henry in 1887. For a time, the company seems to have passed to Henry’s son Hermann, though the German end of the business, and perhaps eventually its American arm too, devolved to former Reiche collectors, Paul and Louis Ruhe.[17] In any event, dominance of the American animal trade soon passed to others, primarily Carl Hagenbeck, though much of it continued to be transacted in New York City. It would take several decades, until the emergence of Henry Trefflich in the 1930s, for another New York-based entrepreneur to achieve the Reiches’s level of market capture and media visibility.

Henry Trefflich, Undated, Though Likely From a 1967 or 1968 Radio Appearance on the Long John Nebel Show. Photo Courtesy of Wikipedia

Like Reiche, Trefflich was a German immigrant to the United States, though they seemingly have no direct connection. Born in Hamburg, Germany in 1908, Trefflich’s father was an animal trader as well, and his son carried on the family business upon moving to the United States in 1928. Soon, Trefflich’s outsized personality and zany business attracted a similar stream of headlines and notoriety. From a shopfront on Fulton Street, where the World Trade Center now sits, Trefflich became the pre-eminent American animal dealer of his era. Whereas Reiche became most closely associated first with birds, and then with elephants and marine life, Trefflich’s name became synonymous with primates. Indeed, he would become known as the “Monkey King” — his store dubbed by one writer, playfully but perceptively, “anthropoid Ellis Island.”[18]

The moniker was certainly fitting. Though Trefflich dealt in a kaleidoscopic array of animals over the course of his long career, primates were his main attraction, many deriving from a major collecting base in Sierra Leone.[19] At Trefflich’s death in 1978, his New York Times obituary claimed that he had imported an astonishing 1.5 million primates into the United States, almost all arriving at a New York City airport or seaport.[20] By and large, these animals were sacrificed to America’s burgeoning medical research establishment — Trefflich took particular pride in the many animals he provided to the polio vaccine trials.[21] Though Trefflich became fond of many of the primates he handled, he does not seem to have dwelt upon the fates of those destined for the laboratory.[22] Perhaps he simply thought the virtuous aims of medical research worth the cost. Alternatively, he may simply have been unaware of how many animal experiments were (and are) repetitive and unnecessary, or how little stimulation and satisfaction primates derive from laboratory life.

In any case, Trefflich also had other destinations in mind for his primates beyond the research lab, or even the zoo and circus. He was a major proponent of personal exotic pet ownership, memorably claiming to want a “monkey in every home.”[23] Trefflich thought a monkey made a particularly good solution to empty nest syndrome, advising parents of grown children to adopt one.[24] After all, they were like children except “they only cost $500 or $1,000 and you don’t have to educate them.”[25] Trefflich also routinely dispensed big cats to American households, remarking in 1968 that he sold “lion and tiger cubs to private homes every day of the week.”[26] Elsewhere, he recommended personal pet ownership of pythons, and admitted to selling leopards to women “with feline instincts” and ocelots to women hoping to match their fur coats.[27]

But as time passed, Trefflich’s trade began to seem increasingly tawdry and unethical. Displaced by the World Trade Center complex in the 1960s, Trefflich’s once-lucrative business declined badly by the early 1970s, prompting his retirement. For historians like Daniel Bender, the sunset of Trefflich’s store also represented the end of an era in the animal trade.[28] It had become less acceptable to peddle exotic animals as more attention focused on their abysmal rates of attrition during the journey from wild to captive. Feeling that pressure, zoos themselves turned to captive breeding more and more. Greater awareness of the potential extinction of charismatic megafauna also galvanized international and domestic laws to protect them, as well as backlash against the animal importers and the criminal smuggling networks often on the other side of the American animal trade.

So, did the heyday of the animal trade in New York City pass with the death of Henry Trefflich? Maybe, though perhaps it has merely become less conspicuous. Primates are still imported into the United States in their tens of thousands every year to serve the medical research industry.[29] While many zoos and aquaria have backed away from obtaining rare species, especially those which are palpably unhappy in captivity, they still do acquire animals, particularly marine life. Meanwhile, the exotic animal trade continues, often in illicit form. American customs authorities annually seize millions of dollars in animal appendages destined for varied uses ranging from clothing to dubious health tonics.[30] Moreover, charismatic species like tigers and lions still find their way legally, or otherwise, into the United States to tickle the fancies of the nation’s exotic animal aficionados. All told, the often-squalid worldwide trade in animals continues, even if its main participants now generally shun rather than court the spotlight. But the development of a more-than-human history of New York City — and America — has only just begun.

Barrie Blatchford is a doctoral candidate at Columbia University specializing in American environmental history. His dissertation explores the modern history of the American fur industry and its impacts on American environments, consumer culture, and animal ethics.

[1] In the interests of simplicity, I adhere to the human/animal binary description hereafter instead of constantly stipulating “nonhuman animal.” Of course, humans are also animals and I do not wish to perpetuate any notions that we are separate, or better than, the rest of the planet’s animals.

[2] I recognize that likening human and animal “immigration” might seem ill-fitting — for many reasons, animals can only awkwardly inhabit our categories for migrant people. Yet I think this framing is generative, and the similarities are greater than the differences. Moreover, to classify animals as mere property unjustly denies their sentience and individuality.

[3] Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe 900-1900 (New York: Cambridge University Press: 1986), 171-193.

[4] The Reiches are equally obscure in the historiography on zoos and the animal trade. Elizabeth Hanson and Katherine Grier mention them, but only in passing. Richard Flint offers more extensive, but hardly comprehensive, commentary. See Elizabeth Hanson, Animal Attractions: Nature on Display in American Zoos (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 79, 83; Katherine C. Grier, “Buying Your Friends: The Pet Business and American Consumer Culture,” in Susan Strasser ed. Commodifying Everything: Relationships of the Market (New York: Routledge, 2003): 47-48; Richard W. Flint, “American Showmen and European Dealers: Commerce in Wild Animals in Nineteenth-Century America,” in R. J. Hoage and William A. Deiss eds., New Worlds, New Animals: From Menagerie to Zoological Park in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997), 101-105.

[5] On Charles’ claim, see Charles Reiche, The Bird Fancier’s Companion: Tenth Edition (New York and Boston: Charles Reiche & Brother, [1853] 1871), viii. On the 500,000 figure, see Reiche associate Charles Holden, Holden’s Book on Birds (Boston: New-York Bird-Store Publishers, 1875), 111-112.

[6] On the sparrow, see Ibid., 65-66. The canary claim could be apocryphal. Nevertheless, see Amelia Mayberry, American Canary Bird Culture (California: Whittier News Co., 1924), 8.

[7] “Birds! Birds! Birds!” The Interior, Mar. 5, 1874, 5. The Reiches even started an ostrich farm in Florida in the 1880s in hopes of capitalizing on the fashion feather trade. “The Florida Ostrich Farm: How the Great Birds Are Doing at Sylvan Lake,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, reprinted from New York Telegram, Aug. 5, 1884, 7.

[8] Though it is immaterial to the overall influence of the company, I depart from previous work by suggesting that Charles led the enterprise in the United States and Henry was commonly, though not exclusively, in Germany. Grier states that Charles Reiche relocated to Germany “permanently” by at latest 1870 with Henry remaining stateside, though her source is unclear (p. 47). Flint says that Charles Reiche returned to Germany in 1860 until his death in 1885, but supplies no direct citation (p. 101-102). It is true that the evidence is ambivalent, and there are sources which indicate Henry was in the United States often and running the business. Yet numerous articles in New York City newspapers quoted Charles Reiche and described his various New York City activities in the 1870s and 1880s. Also, several sources expressly state that Henry managed affairs in Germany and Charles ran things stateside. See, for example, “Hunting Beasts in Africa,” Saturday Evening Post, Sep. 29, 1877, lvii, 10, and the memoir of the Reiches’ former business partner in the New York Aquarium, W. C. Coup, Sawdust and Spangles (Chicago: H. S. Stone and Co., 1903), 20-21. Nevertheless, Henry was clearly in the United States often too, particularly in the 1880s. See “Recollections of a Showman,” New York Times, Jun. 18, 1887, 2.

[9] “Editorial Notes,” New York Evangelist, May 21, 1874, 4.

[10] “Elopement of the Daughter of a Millionaire,” Daily American, Sep. 20, 1877, 3. Grier (p. 47) says the Reiche firm was worth $30,000-40,000 in 1870, but Flint (p. 102) contends it was worth $100,000-150,000 in that year, and $300,000 in 1883. Neither supply numbers for Reiche’s personal net worth, which would certainly be higher than the value of the business at any given point.

[11] Reiche v. Smyth, Collector, 80 U.S. 162, 20 L. Ed. 566, 13 Wall. 152 (Supreme Court, 1871).

[12] Flint, “American Showmen,” 104-105; H. Dorner, Guide to the New York Aquarium (New York: D. I. Carson and Co., 1877), passim; “Two Small Elephants,” New York Times, Oct. 9, 1880, 3.

[13] It was the first dedicated aquarium in New York City, though P. T. Barnum’s ill-fated American Museum featured marine life before its fiery demise in 1865. Amanda Bosworth, “Barnum’s Whales: The Showman and the Forging of Modern Animal Captivity,” Perspectives on History, 56, 4 (2018): 17-19.

[14] Whether Reiche believed this or was just seeking attention is uncertain. “In and About the City: Science to be Surprised,” New York Times, Sep. 18, 1884, 8.

[15] “North Africa: Rare and Curious Animals that Are Destined to Recruit the Travelling Shows,” Chicago Tribune, reprinted from the New York Daily World, Jun. 4, 1882, 6 (original printed on Jun. 2, 1882).

[16] “Selling a Big Elephant: A Curious Auction Sale at Hoboken Yesterday Afternoon,” New York Times, Mar. 26, 1882, 14. The same article also notes the harsh treatment meted out upon Reiche’s orders to a pair of barely-ambulatory guanacos (a llama-like creature).

[17] Hanson, Animal Attractions, 79; Flint, “American Showmen,” 105.

[18] Leslie Lieber, “King of the Monkeys,” Washington Evening Star, Jan. 11, 1948, 10, 14.

[19] Robert D. McFadden, “Henry H. F. Trefflich, Importer of Animals, Dies at 70,” New York Times, Jul. 9, 1978, 2.

[20] Ibid. Trefflich was the pioneer of the airline animal trade, in fact, in the wake of WWII. See John Stuart, “The Animal Act Draws Airlines,” New York Times, Sep. 11, 1955, 1, 8.

[21] Trefflich also supplied primates for NASA’s early space missions. On that and his contributions to fighting polio, see Henry Trefflich and Edward Anthony, Jungle for Sale (New York: Hawthorn Books, 1967), 4.

[22] Trefflich discloses in his ghostwritten autobiography his affection for a monkey named Sam, as well as for another male named Bonzo. However, he still sold Bonzo to Yale University neurophysiologist John Fulton, despite regrets. Sam died of poisoning courtesy of a disturbed store patron. See Ibid., 91, 96-97.

[23] “Pet Industry Soars with Monkey Sales,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 17, 1968, A8.

[24] Lieber, “King of the Monkeys,” 14.

[25] “Pythons Advocated as Pets by Dealer Who Should Know,” Wilmington Morning Star, May 11, 1947, 7B.

[26] “Pet Industry Soars with Monkey Sales,” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 17, 1968, A8.

[27] “Pythons,” May 11, 1947, 7B.

[28] Daniel E. Bender, The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016), 307-310.

[29] Emma Newburger, “Trump’s Tariffs on Monkeys Could ‘Severely Damage’ US Medical Research and Send Labs to China,” CNBC, Aug. 24, 2019.

[30] The former chief of the US Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that $10 million in illegal wildlife products was seized each year at US ports from 2004 to 2008. U. S. Congress, House, Committee on Natural Resources, Poaching American Security: Impacts of Illegal Wildlife Trade, 110th Cong., 2d Sess., 2008. H. Doc., 39.