“Mortars over Stapleton Heights”: Audre Lorde on Staten Island

By David Allen

In May 1985, Audre Lorde participated in a daylong event sponsored by Sisters in Solidarity against Apartheid, a student group at the University of California Berkeley. Lorde introduced one of the poems she would read this way:

I live quite close to the Verrazano Bridge, which is the bridge that connects Staten Island with the rest of New York City…. On a trip to San Francisco, not too long ago, I happened to look down and realized that the plane was circling the bridge and therefore, circling my house. And it seemed, for me, very symbolic—one of the ways in which we are both connected and letting go.

Characteristically, Lorde challenged her listeners: “What you get from this poem, I ask that you hold and use.”[1]

In the poem, “On My Way Out I Passed Over You and the Verrazano Bridge,” Lorde contemplates leaving Staten Island where she had lived for nearly thirteen years. Her connections to the place were complex, bringing together her love of nature, her need for a place to write and work, to be with her lover and her children, as well as with other poets and activists. All these had come to pass within a social and political climate inscribed with racism, homophobia, and violence.

The broad water drew us…

It might puzzle some why Lorde, a gay Black woman, would move from Harlem, the neighborhood of her birth, so closely associated with her work, to Staten Island — then, as now, the whitest and most politically conservative of New York City’s boroughs.

Some of her reasons for moving from the apartment on Riverside Drive she shared with Ed Rollins, whom she divorced in 1970, and their two children are provided by the poem:

The broad water drew us, and the space

Growing enough green to feed ourselves over two seasons

References to Lorde’s garden on Staten Island recur frequently in her poems; she told one interviewer: “Well, you know, moving to Staten Island, it was the first time I’d lived very closely with green. I have a vegetable patch, grass, a tree.[2]

207 St. Paul’s Avenue (photo by author)

Lorde’s house at 207 St. Paul’s Avenue in Stapleton Heights is a three-story Victorian house with a porch, small front yard, and larger back yard. Its back windows overlook the Stapleton neighborhood, New York Harbor, and South Brooklyn. Lorde made it a welcoming place to many friends. Clare Cross and Blanche Wiesen Cook, recalled “the climb up the big front porch steps, the door bell’s ring” followed by the sounds of Lorde’s children “thundering down the staircase from their respective rooms.”[3] To another friend, Pat Parker, Lorde sent an aerogram with a hand-drawn rabbit and “What’s Up Doc?” and the message, “When are you coming?” And, in a 1985 letter, she wrote: “We would both love to have you stay in lovely scenic downtown Staten Island!”[4]

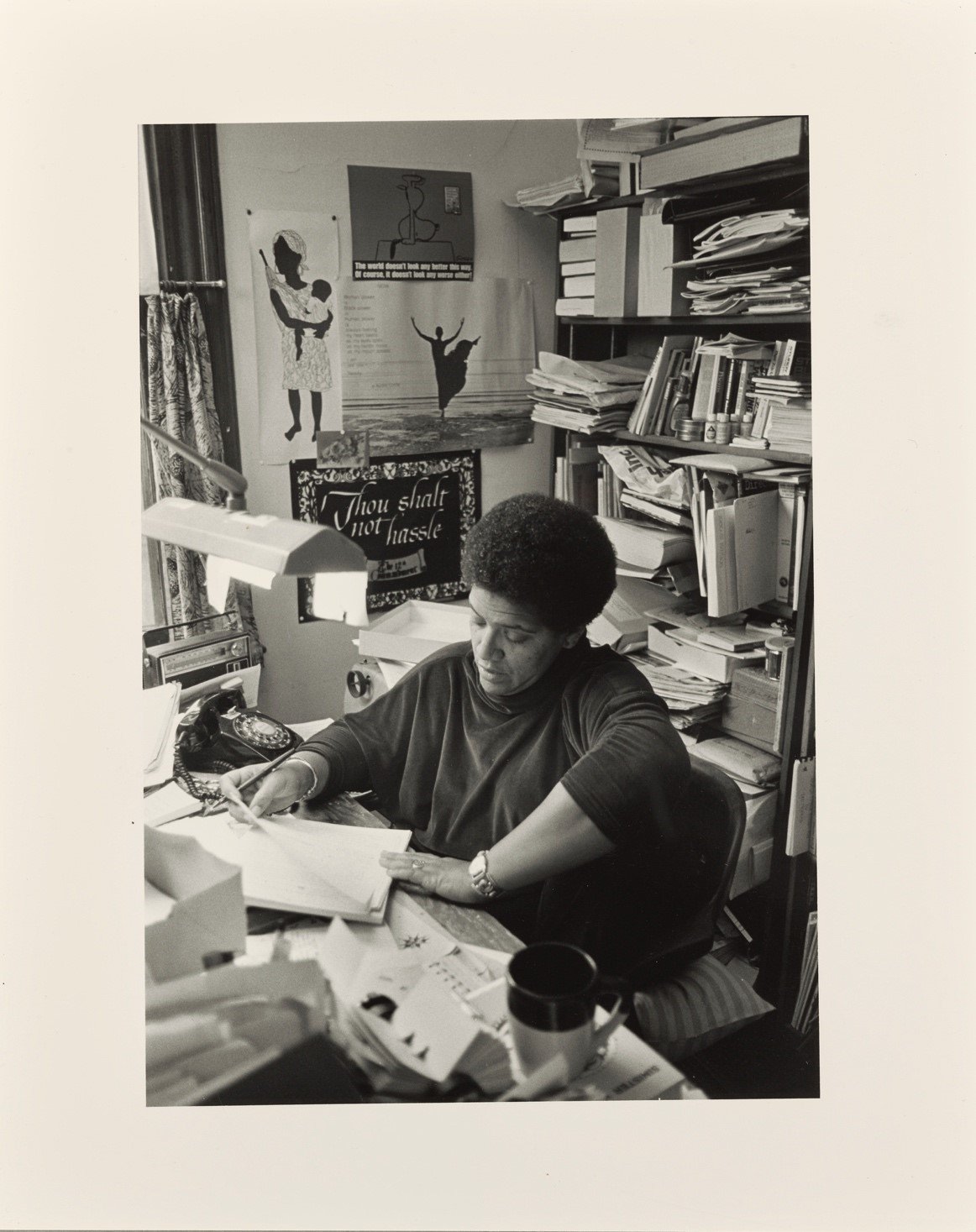

Lorde’s study, 1981 (photo: Joan E. Biren; used by permission, Getty Museum)

The house provided the space for Lorde and her fellow writers and activists to produce Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, which Lorde founded with Barbara Smith in 1980. Crucially, it gave Lorde a private workspace in which to think and write: “I have a study upstairs and I pull it around me like a blanket. There’s a force field around it. [...] The force field keeps everyone out unless they’re invited in.”[5]

Lorde may have known that, while not as storied as Harlem, Stapleton was also an historic African American neighborhood. A small community of freed slaves had forsmed in Stapleton by the early 1800s. The 2nd African Methodist Episcopal Church on Tompkins Avenue was constructed on land purchased in 1850 by John W. Blake and his wife Tabitha.[6] Now known as the United Methodist Episcopal Church, it still serves parishioners across from the Stapleton Houses public housing complex — birthplace of the Wu-Tang Clan. From Lorde’s house, it is about a five-minute drive to the Park Hill Houses, the other home for members of Wu Tang, and now the center for the largest Liberian emigre communities outside of Liberia.

Lorde’s move to Staten Island at this time is echoed in the stories of other African American families. Marcia Lyles, retired superintendent of schools in Jersey City and longtime New York City educator and administrator, recounts her own move from Harlem to Staten Island:

I was married, had a young son, and couldn't find affordable housing in Manhattan. We didn't know anybody here in Staten Island, didn't know anything about… Well, we knew about Staten Island, but there was a particular quality of life we were seeking, and we could afford it in Staten Island. [6]

It did not take long for Lyles to run up against the realities of race on Staten Island.

Looking for a teaching job on the island, a Board of Education administrator told her he would send her to New Dorp High School on the island’s mostly white South Shore. Aware of that area’s racist reputation, Lyles responded: “New Dorp? Well, then I'm not going to work because I'm not going to New Dorp High School." In the end, he sent her to “integrate” Curtis High School, close to her neighborhood on the more diverse North Shore, becoming one of just four African Americans on the faculty.[7] Some years later, Audre Lorde’s daughter would briefly be her student.

Staten Island historian Debbie-Ann Paige’s parents rented an apartment in Park Hill in 1969, one of the first African American families to do so. She and her friends “never actually walked down Vanderbilt to Bay St.,” a main business artery for North Shore neighborhoods. At that time, a concrete wall ran along the avenue providing a symbolic barrier to the mainly white Rosebank neighborhood. Painted on it was “N.N.L.,” understood by all to mean “No Nigger Land.”[8]

In 1988, The New York Times reported on the investigation of the death of Antonio Tyrus, a Black youth from Park Hill who was killed by a car on a “rain-slicked street” in Rosebank fleeing a “racial incident.” Not surprisingly, white residents of Rosebank and Black residents of Park Hill viewed the inquiry differently. While Blacks were skeptical, many whites in Rosebank “said that precisely because Mr. Tyrus was Black, authorities were bending over backward to find out what happened to him.” Among the signs spotted by the Times reporter were those that read: “Death to All Niggers” and “Rosebank No. 1 K.K.K.”[9]

In 1973, Lorde had written a poem titled “Power” about the killing of a ten-year old Black boy in Queens by a white police officer. At the time, Lorde was teaching at John Jay College in Manhattan, known for its programs in law enforcement. She told Adrienne Rich about her reaction to the news of the officer’s acquittal: “I felt so sick and so enraged…. I was thinking that the killer had been a student at John Jay and that I might have seen him in the hall…. What was retribution? What could have been done? [...] Do I kill him?”[10] Such thoughts may have occurred often to Lorde on Staten Island, where many NYPD officers lived then, as many do today.

Walking our boundaries: The Staten Island poems

Audre Lorde’s first poem that mentions Staten Island is “A Trip on the Staten Island Ferry,” from a collection published two years after her move there. A short, lyrical poem, it takes the form of a letter beginning “Dear Jonno” (for her son, Jonathan). Lorde contemplates the “old men/who shine shoes on the Staten Island Ferry” who “carry their world/in a bag across their shoulders.” She relates their back-and-forth journey to that of the pigeons

who nest

on the Staten Island Ferry

between the moving decks

and never touch

ashore.

In “Scar,” published a year later, Lorde gives her attention to “the women who clean the Staten Island Ferry,” presumably at night when the ferry would be less crowded. As in the earlier poem, Lorde recognizes people who are invisible to regular ferry riders. In “Scar” she does more, enlisting the cleaning women within a sisterhood she celebrated throughout her work and life as an activist: “all the mothers sisters daughters/girls I have never been.” They join Lorde on “a tideless ocean of moonlit women/in all the shades of the loving.” In their swabbing movements, Lorde perceives a

dance of open and closing

learning a dance of electrical tenderness

to a father no mother would teach them.

In neither poem has Lorde figuratively “touched ashore” on Staten Island. When she does, it would be from 207 St. Paul’s Avenue that she would view Staten Island. In “Walking Our Boundaries,” Lorde and her lover would “cautiously inspect [their] joint holding” after the rigors of their first winter:

The first bright day has broken

the back of winter.

We rise from war

to walk across the earth

around our house [...]

They are sad to see “there will be no tight buds started/on our ancient apple tree/so badly damaged by last winter’s storm” and note the “siding has come loose in spots.” Despite the damages, the garden provides a place for regenerative work in a time of despair:

I do not know when

we shall laugh again

but next week

we will spade up another plot

for this spring’s planting.

In the unpublished “A Staten Island Poem,” Lorde ventures beyond house and yard to describe her neighbors.

[…] The old man down the way

lets his dog shit on my lawn

while he tries to peer behind our curtains

and the woman in the grocery

on the corner

insists I call her Rosie

but she keeps her eyes upon me

throughout the store. […]

In “Outlines,” written near the end of Lorde’s time on Staten Island, the experience of being watched gives way to a sense of menace:

Ten blocks down the street

a cross is burning

we are a Black woman and a white woman

with two Black children

you talk to our next-door neighbors

I register for a shotgun

Among Lorde’s papers at Spelman College Library is an article from the Staten Island Advance from September 1979 reporting on cross burning in the south shore neighborhood of New Dorp. Given the testimonies of Marcia Lyles, Debbie-Ann Page, and other African Americans living on the North Shore, it is not difficult to believe that one occurred just down the street from Lorde and her family.

Leaving, leaving

In “On My Way Out I Passed Over You and the Verrazano Bridge,” Lorde views Staten Island, her home for nearly fifteen years, from an airplane gaining altitude she begins:

Leaving leaving

the bridged water

beneath [...]

in the nape of the bay

our house slips under these wings

shuttle between nightmare and the possible.

Verrazano-Narrows Bridge (photo by author)

The poem’s images and events signal what Staten Island and New York had become for her, in terms of ecological degradation, racism, and violence. Coming to Staten Island, Lorde had found the space to “[grow] enough green to feed ourselves over two seasons.” But “now sulfur fuels burn in New Jersey/and when I wash my hands at the garden hose/the earth runs off bright yellow.” Even the bridge “disappears” in the smoggy air. (In an unpublished, undated poem, “The Shores of Staten Island Smell like a Southern Delta,” Lorde describes a day at the beach with her children: “I warn them-/not to swallow water/because it is polluted.” Her daughter pats her arm “reassuringly” and says, “Maybe it’s only red.”)

Lorde’ despair for the environment ushers in a broader apocalyptic question:

So do we blow the longest suspension bridge in the world

up from the middle

or will be bombs at the Hylan Toll Plaza

mortars over Grymes Hill

flak shrieking through the streets of Rosebank

the home of the Staten Island ku klux klan

while sky-roaches napalm the Park Hill Projects

An earlier draft had the mortars over Stapleton Heights itself.

* * *

Lorde’s longest piece completed on Staten Island is The Cancer Journals. Written over 1978 to 1980, the entries describe Lorde’s experiences following a mastectomy for breast cancer. Coming home to Staten Island from Beth Israel Hospital in Manhattan was a mixed virtue for Lorde:

The prospect of returning to Staten Island and the house was freighted with ambiguity:

Going home to the very people and places that I loved most, at the same time as it was welcome and so desirable, also felt intolerable, like there was an unbearable demand about to be made that I would have to meet. And it was to be made by the people I love, and to whom I would have to respond.[11]

“Different questions” suddenly confronted her: “Not, for how long do I stand at the window and watch the dawn coming up over Brooklyn, but rather, how many more new people do I admit so openly into my life?”[12]

Several days after reading The Cancer Journals, I drove to Lorde’s house. There is a small sign where St. Paul’s Avenue diverges from Victory Blvd.: “NYS Poet Laureate Audre Lorde Way,” but no sign on the house itself indicating Lorde had lived there. I hoped to meet the current owners, and, if lucky, get a tour of house and garden. I opened the wrought iron gate and walked up the steps to the front porch. I couldn’t find the doorbell Cross and Cook had described from their many visits. Though a car was parked in the short drive, my knocks went unanswered.

I peeked around the side of the house to see a neatly laid out garden in the backyard, with early shoots of vegetables in the May sun; Lorde would have approved. As I sat on the porch and wrote a note to leave for the current owners, I thought about how much the house and garden had meant to Lorde’s survival — of racism and violence, homophobia, and — for a time — cancer. At the same time, Staten Island became a place to be survived.

In “A Litany of Survival,” one of Lorde’s best known poems, she wrote:

For those of us who live at the shoreline

standing upon the constant edges of decision

crucial and alone.

Staten Island’s was surely one of the shorelines she had in mind. There she wrote many of her most important poems. These, along with Cancer Journals, Zami-A New Spelling of My Name, essays, speeches, and interviews, as well her teaching at CUNY, editing of Kitchen Table, inspire and equip for survival generations that have followed.

David Allen is a professor of English Education at the College of Staten Island CUNY. He has previously published an article on Dorothy Day on the Gotham Blog.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges for their assistance: Marcia Lyles, Debbie-Ann Paige, Kassandra Ware of the Spelman College Archives, the Getty Museum, the Arthur & Elizabeth Schlesinger Library, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Unless noted, excerpts from poems are from The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997).

[1] Lorde, Audre, “On My Way out I Passed over You and the Verrazano Bridge.” Feminist Studies, 14, no. 3 (Autumn, 1988): 446–49.

[2] Chwala, Louise, “Poetry, Nature, and Childhood: An Interview with Audre Lorde,” in Conversations with Audre Lorde, ed. Joan Wylie Hall (Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi, 2004): 122.

[3] Cross, Clare and Blanche Wiesen Cook, “Offering: A Few Moments Across the Decades with Audre Lorde,” in The Wind Is Spirit: The Life, Love and Legacy of Audre Lorde, ed. Gloria I. Joseph (New York: Villarosa Media, 2016): 35-36.

[4] Enszer, Julie R. (ed.). Sister Love: The Letters of Audre Lorde and Pat Parker, 1974-1989 (Dover, FL: Midsummer Night’s Press, 2018): 34, 60.

[5] Hammond, Karla M., “Audre Lorde,” in Conversations with Audre Lorde, ed. Joan Wylie Hall (Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi, 2004): 39.

[6] Staten Island African American Heritage Tour, accessed May 15, 2022, https://statenislandaframhistory.oncell.com/en/index.html.

[7] Lyles, Marcia, in discussion with the author, October 2021.

[8] Paige, Debbie-Ann, in discussion with the author, August 2021.

[9] Sam Howe Verhovek, “Race and a Death Dividing two Neighborhoods on S.I.,” New York Times, October 17, 1988.

[10] Rich, Adrienne, “An Interview with Audre Lorde,” in Conversations with Audre Lorde, ed. Joan Wylie Hall (Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi, 2004): 67-68.

[11] Lorde, Audre, The Cancer Journals: Special Edition (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1997): 57.

[12] Ibid.