Two Hundred Fifty years of Organ-Building in the City, Part II: 1850 to 1930: New York Becomes a City of Organs

By Bynum Petty

In 1800 — the birth year of Henry Erben — the population of New York City was 60,515, consisting of many tradesmen and shopkeepers who lived over their places of business with their families (still true today for some organ builders residing over their workshops). This population established about thirty churches, most of which had no organ — certainly a growth opportunity for the two or three resident organ-builders. Fifty years later, the city’s population had grown to more than 515,000 and more than 250 houses of worship had been erected; of these, about six Reform Synagogues had pipe organs. Rightly assumed, the greatest growth in pipe organ building was in Christian places of worship, both Catholic and Protestant; but proportionally, growth was just as strong in Jewish houses of worship. In itself not an impressive number, over the next 125 years many of the city’s most significant organs were commissioned by Reform Temples, those primarily established by German immigrants fleeing the Kristallnacht riots of November 1938. The first Reform congregation in the city to incorporate a pipe organ into its worship service was Temple Emanu-El, then located at Fifth Avenue and Forty-third Street; ironically the organ was built by Henry Erben in 1848, who if you recall from Part I, boasted to have “never built an organ for the detested race yet, and I never will. And I never’ll build an organ for the Unitarians, either. They’re just as bad as the Jews — every whit.” [1] To repair Mr. Erben’s foggy memory, one should know that he built organs for Jewish worship spaces as well as the Unitarians.

Henry Pilcher’s Sons organ, 1928, in Second Church of Christ, Scientist (now First Church of Christ, Scientist), Central Park West at Sixty-eighth Street. Courtesy of the Organ Historical Society.

Significant Jewish houses of worship aside, the overwhelming number of organs built for other sacred spaces were the creations of Jardine, Odell, and Roosevelt. Born the same year as Henry Erben, George Jardine was in all respects, the antithesis of Erben. While Erben’s education was sketchy and streetwise, George Jardine was a gentleman of Erben’s own age. Born on November 1, 1800, in Dartford, Kent County, England, at the age of fifteen, Jardine apprenticed organ-building with Flight & Robson in London. George Jardine’s brother John moved to New York City in 1837, and because of his encouragement, George, his wife, five children, and nephew Frederick, moved into a house at the intersection of Broadway and Grand Street where Jardine set up his workshop in the attic of the house while the family lived on the floors below.

It didn’t take long for George Jardine to become Henry Erben’s main competitor as the high quality of their uncompromising work set them apart from all other organ-builders. While competition may often be much greater than a matter of two titans butting heads, the growth of New York City since the year of their births provided economic conditions from which both profited handsomely. In the fifty years since their births, the city’s population grew ten-fold, while religious worship spaces expanded to over 350. Not only did this growth provide Erben and Jardine “elbow room,” it provided opportunity for younger talent to set up shop, taking the city into its zenith of pipe organ construction and influence. On the birth year of Erben and Jardine, New York City’s pipe organ hegemony was unchallenged, save but one — Boston. All this would soon change, however, placing Boston from front-runner to runner-up.

Although Erben and Jardine were the same age, both tonally and mechanically, Jardine’s style of organ design was much more progressive. In 1855 Jardine’s oldest son, Edward G. was made a partner in the business, and continuing as George Jardine & Son, the organ for Church of St. John the Evangelist at Madison Avenue and Fiftieth Street (1864) marked a bold departure from earlier visual designs. Above the impost, there was no wooden case, but rather painted display pipes — both metal and wood. In the center were fanned trumpet pipes with flared resonators. Unfortunately, both the organ and church building were destroyed by fire in 1871.

Jardine organ, 1864, in St. John the Evangelist Church, Fifth Avenue and Fiftieth Street. The church and organ unfortunately were consumed by fire in 1871. Drawing from Catholic Churches of New York, 1871.

Likewise no longer extant, Jardine’s 1869 organ at St. George’s Church, Stuyvesant Square, stands out as one of his most memorable works. The organ was pumped by water-power from a 10,000 gallon tank in one of the two west-end towers of the church, from which the water would fall and collect into a basement vat; there a steam engine would pump the water back into the tower – a unique system suggesting an unreliable city water supply. [2] Leopold Eidlitz, architect of the church, designed the pipe display with its characteristic flared resonators of the Tuba Mirabilis. [3]

Jardine organ, 1869, in St. George’s Church, Stuyvesant Square. Photo from Blanton, Joseph E. The Organ in Church Design (1957). Courtesy of the Organ Historical Society.

While less radical in design, the Jardine organ for Congregation B’nai Jeshurun (1884) made way for the organs at St. John the Evangelist and St. George’s Church. The B’nai Jeshurun organ was built for the congregation’s second location at Madison Avenue at Sixty-fifth Street, a striking creation of Rafael Guastavino. The synagogue was fashioned after the first temple erected in Toledo, Spain, with strong Byzantine and Moorish visual elements. The organ façade blends seamlessly into this design. [4]

Temple B’nai Jeshurun, Thirty-fourth Street at Sixth Avenue. Drawing Courtesy the New-York Historical Society.

Jardine Organ, 1884, in Temple B’nai, Thirty Fourth Street at Sixth Avenue. Taken from The Decorator and Furnisher (October 1885).

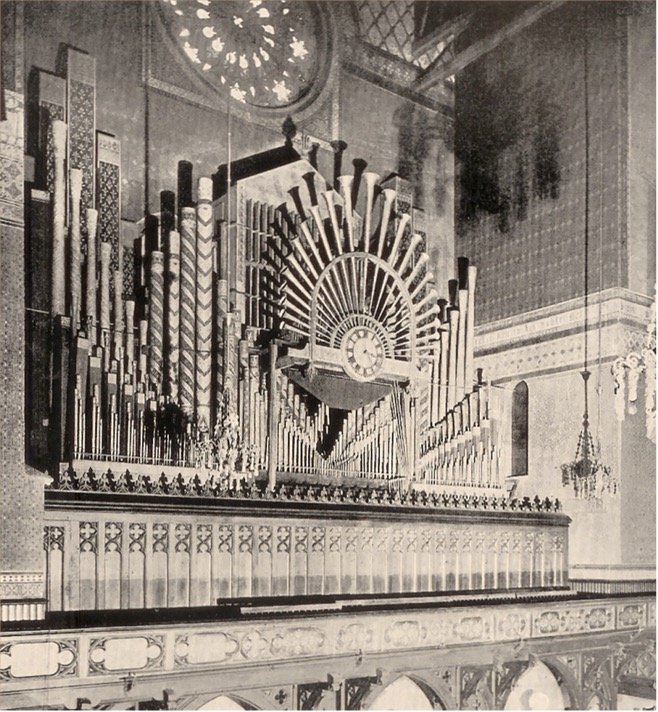

As successful as they were, neither Erben nor Jardine could equal the longevity of the Odell brothers. John H. and Caleb S. Odell were born in Yonkers and established their business in 1859. They set up shop in a rented space on Seventh Avenue between Nineteenth and Twentieth Streets, one that soon became inadequate because of the great volume of business. Eight years later, they erected their own building on West Forty-second Street, where they built over 600 organs until the virtual close of their manufacturing activities in 1957.[5] The most prominent Odell organ built in the city was for Temple Emanu-El then located at Fifth Avenue at Forty-third Street. Completed in 1868, the Moorish style building was designed by Leopold Eidltz and Henry Fernbach and was home for the congregation for the next fifty-nine years. The Odell organ was a magnificent structure installed in 1901, replacing the original organ built in 1869 by Hall, Labagh & Co., New York City.

Odell organ, 1901, in Temple Emanu-El, Fifth Avenue and Forty-third Street. Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

That same year, the young Hilborne Roosevelt — himself not quite nineteen years of age — filed a patent application for a new pipe organ mechanism, thus establishing a brief but extraordinary era of organ-building in New York City. [6] Hilborne Roosevelt was born in New York City in December 1849. His father was Silas Weir Roosevelt, and his first cousin, Theodore, became the twenty-sixth president of the United States. While the family disapproved, Hilborne apprenticed organ building at Hall & Labagh, after which he established his own organ-building company. At the age of twenty-two, his first job was to build an organ for Holy Communion, the family’s parish church at Twenty-sixth Street at Sixth Avenue. Even with the vast amount of inherited wealth at his disposal, Roosevelt’s organs were costly to build. For Roosevelt, however, profit was not the priority; rather, building organs of the highest quality was his goal. As such, when compared to the quantity of organs produced by Erben and Jardine, Roosevelt’s work appears almost insignificant, save for the craftsmanship and tonal quality they exhibit that place them as the paragon of New York’s organ scene.

This was evident in the organ Hilborne Roosevelt designed for the new Chickering Hall that attracted the attention of the New York Times, which printed the following: “The exhibition, as already noted, threw abundant light upon the qualities of the instrument. Some of the effects — particularly those produced by the skill of Mr. Whitely — were uncommonly beautiful, and the voix céleste approximated so closely to the ideal of angels’ chants, that the assemblage broke out into rapturous applause almost before the sounds had died away.” [7]

Hilborne Roosevelt organ, 1876, in Chickering Hall, Fifth Avenue and Eighteenth Street. Courtesy of the New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists.

Hilborne Roosevelt’s organ building was cut short, however, dying of an unspecified respiratory condition in 1886 just days after his thirty-seventh birthday. As of that date, his company had completed about 400 organs, the largest being for the Cathedral of the Incarnation, Garden City. [8] Nevertheless, the firm continued. After the death of Hilborne, his brother Frank assumed leadership of the company to its end six years later. During those last years, Frank Roosevelt continued to garner praise, building organs for two significant secular spaces, Carnegie Hall (1891) and Mendelssohn Hall (1892).

Carnegie Hall was completed in 1891, and in its early years was the shared home of the Oratorio Society of New York and the New York Symphony Society. While New York’s finest organ builder was selected to build an instrument for the new hall, the Roosevelt organ’s presence was short-lived. It was replaced by an organ built by an Ohio firm in 1916, which in turn was replaced by an unsuccessful instrument from a Missouri firm in 1929. No further attempts have been made to fit the hall with a pipe organ suitable for the acoustical space. [9]

Frank Roosevelt organ, 1891, in Carnegie Hall. Courtesy of Carnegie Hall Archives.

Located on Forty-second Street between Sixth Avenue and Broadway, the Mendelssohn Glee Club built Mendelssohn Hall with the financial underwriting of Alfred Corning Clark, a chief stockholder in the Singer Sewing Machine Company and Glee Club member. The concert hall seated more than 1,000 people. On the floors above, apartments were available for bachelors, while below there were smoking rooms, library, and a dressing room for the ladies. Frank Roosevelt’s Opus 523 – the instrument that filled the hall with sound - was one of his last produced. As with so many other instruments of this era, it was unceremoniously destroyed when the building was razed in 1912.

Henry Pilcher, c. 1846. Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.

Thus, the work of the Roosevelt brothers takes us to the end of nineteenth-century organ-building in the City of New York. Organs, of course, were still being built, but by outsiders; a trend that continues today. But before the book is closed on the history of organ-building in New York, an examination of two of those “outsider” firms, working from Kentucky and Maryland, is of interest.

In 1820 Henry Pilcher established himself as an organ-builder in Dover, Kent, and for 125 years, he and four generations of descendants built pipe organs, first in England and then in the United States. Pilcher emigrated from England in 1832 and first settled in Newark, Jersey; afterwards, he moved to New Haven, Connecticut.

In 1844, he and his family took up residence in a small house at 13 Vandewater Street in lower Manhattan, located a few feet from the intersection of Vandewater and Frankfort Streets, and from there it was a short walk to Henry Erben’s workshop at 172 Centre Street, where Pilcher found reliable employment. Later he was building organs in Newark. From Newark, his two sons, Henry Jr. and William moved the workshop to Louisville, Kentucky, doing business as Henry Pilcher’s Sons. Pilcher’s production peaked in the late 1920s, and one of its greatest organs was built for Second Church of Christ, Scientist, Central Park West at Sixty-eighth Street. [10] This rare extant example of Pilcher’s work was recently restored by Brooklyn organ-builder Lawrence Trupiano. With the onset of World War II, however, the company faced financial challenges, and closed its doors in 1944 with its goodwill and stock of supplies sold to M.P. Möller Organ Company.

Neighborhood of Henry Pilcher with his house located at 13 Vandewater Street. “D.T. Valentine’s Manual of the City of New York.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Finally, no history of organ-building in New York City would be complete without mention of M.P. Möller Organ Company. While not a New York City organ-builder, the firm sold more organs to city institutions than all its competitors combined. The company was established in 1881 by a Danish immigrant who set up shop in Hagerstown, Maryland, where over a period of 110 years, the company produced almost 12,000 organs, with the five boroughs of New York City being its primary market. Its most successful organ in a sacred space was built in 1937 for Church of the Holy Name of Jesus, R.C. on Amsterdam at West 96th Street. This organ represented the leading edge of the American organ reform movement taking place in the early twentieth-century, characterized by tonal clarity, brilliant ensembles, and bright reeds. The organ – still present – is in poor condition but is currently undergoing restoration. Möller’s most significant instrument built for a secular venue was completed in 1931 for the grand ball room of the Waldorf Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue at 49th Street. That particular organ was removed to Montclair State College in 1952, and forty years later the Möller firm closed its doors in 1992, an ignominious end to the world’s largest organ manufacturer.

Ars longa, vita brevis. [11]

Möller, Opus 6570 (1937) at Church of the Holy Name of Jesus, Amsterdam Avenue at 96th Street. This organ is currently undergoing renovations. Photo courtesy of Steve Lawson.

Bynum Petty is Archivist Emeritus of the Organ Historical Society and recipient of its Magna Cum Laude Award for distinguished service. He has written four books on various aspects of American pipe organ history; the last, M.P. Möller: The Artist of Organs — The Organ of Artists, was released in January 2024. Previously, he was founder and managing director of Petty-Madden Organ-Builders, a position he held for forty-five years.

[1] “An Old Knickerbocker,” Abilene Gazette 5, no. 52 (December 26, 1879).

[2] Here a brief aside to acquaint the reader with the history of organ-blowing is warranted. Prior to harnessing electricity to provide blown air, man-power — actually leg power — was the single method of proving wind to organs. With the advent of a reliable source of city water, water motors were connected to the organ bellows. This was a trusted and simple method so long as cities maintained a minimum water pressure. Another short-lived [for obvious reasons!] scheme came to life with the invention of the internal combustion engine. Gasoline powered engines were placed in church basements in lieu of water motors. Country churches without city water no longer needed men and boys to pump the organ. Use of these pumps was brief because of fire hazard. See Lawrence Elvin’s Organ Blowing: It’s History and Development (Swanpool: L. Elvin (1971) for a thorough history of organ-blowing.

[3] A loud solo trumpet. Literally from the Latin, a marvelous trumpet. Resonators are the visible portion of a reed pipe. Almost always made of metal, they are often conical or cylindrical in shape, and can look very much like the end of a trumpet bell.

[4] Born in Valencia and educated in Barcelona, Guastavino moved to New York City in 1881 and established himself as a respected engineer, architect, and creator of the Guastavino system of interlocking tiles. Based on the Catalan vault, his tile vaults are found throughout the city, with perhaps the ceilings of the Grand Central Oyster Bar and St. Thomas Church, Fifth Avenue at Fifty-third Street being the most prominent.

[5] The Industrial Revolution had a profound and salutary effect on organ manufacturing in New York City. In addition to Odell’s impressive production, Erben built between 700 and 800 instruments; and while a Jardine work list has never been compiled, it may be assumed that the firm’s production exceeded both Odell and Erben.

[6] Patent number 88,909; 13 April 1869 related to pipe organ electric key action.

[7] “The Organ at Chickering Hall,” New York Times 25, no. 7599 (Saturday, January 22, 1876), 4; Chickering Hall was designed by George B. Post and was located on the corner of Eighteenth Street and Fifth Avenue. It was built for Chickering & Sons to house a music store, warehouse, and Chickering Hall, a 1,450-seat concert hall that occupied the second and third floor spaces. The building was sold and razed in 1901.

[8] This instrument was replaced in 1986 by the Canadian organ builder Casavant Frères Ltée, Opus 3607.

[9] The Kilgen was replaced by a Rodgers digital electronic organ in 1974. A larger Rodgers digital organ was installed in 2006.

[10] In 2003, Second Church of Christ, Scientist merged with First Church of Christ, Scientist, after which Second Church was renamed First Church of Christ, Scientist.

[11] Hippocrates, Aphorisms. c. 400 BCE.