“Not only distressing but truly alarming”: New York City and the Embargo of 1807

By Harvey Strum

From 1793 until 1815 France and Great Britain fought for global supremacy. Both nations seized American ships and cargoes enroute to the other’s ports. Also, the British took American seamen off American vessels and forced them to serve in the British Navy. Many Americans perceived the British assault on American neutral rights as an assault on American sovereignty and independence. Throughout the first decade of the nineteenth century, British warships cruised off New York Harbor, seizing cargoes, ships, and seamen, leading to repeated diplomatic confrontations between President Thomas Jefferson and the British government. While the British did not claim the right to “impress” American born seamen, British naval officers did not care if the seamen came from London or Brooklyn. All told, between 1793 and 1815, the British Navy impressed somewhere between 8,000-12,000 Americans. [1]

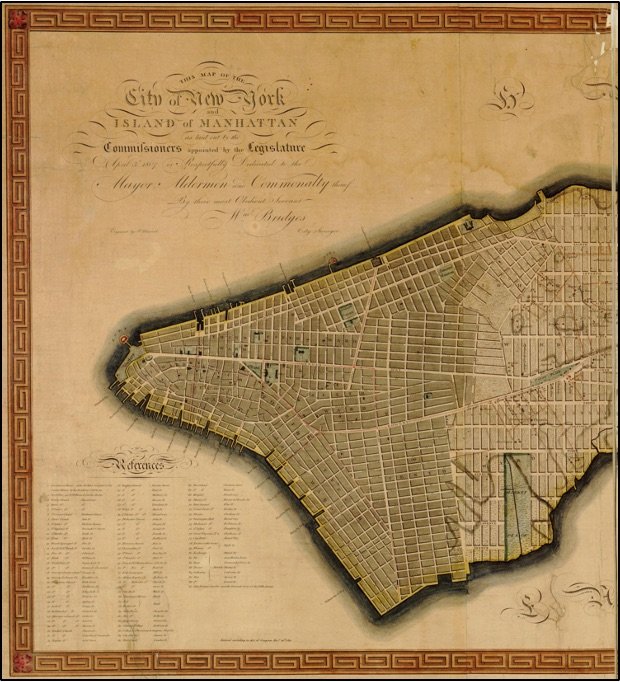

Map of the city of New York and island of Manhattan, as laid out by the commissioners appointed by the legislature, April 3d, 1807. Published 1811. Courtesy of the Library of Congress Digital Collections.

An example of Britain’s boldness occurred on 2 September 1804, when the British warship Leander fired on an American ship John within half-a-mile of the New York shoreline. While John escaped unscathed, New York’s outraged Republican Mayor De Witt Clinton sought to retaliate for the attack, and immediately forbade anyone from further supplying the British ships. Repeated blockading of New York Harbor led the city’s merchants to petition Congress in 1805 for additional funds to defend New York City. Congress failed to vote the funds, however, and President Jefferson lacked the naval resources to take further action since most of the Navy had been dispatched to the Mediterranean.

Another event of note occurred in the spring of 1806, when three British warships blockaded New York Harbor. While some opportunistic New Yorkers readily seized on the chance to make a profit by supplying the warships with provisions, their opportunism was squashed when the warship Leander opened fire on a coasting vessel, Richard, beheading its helmsman, John Pierce, brother of the ship’s captain. In response, a mob gathered and stopped the pilot boat crew carrying provisions to the three warships. Loading the provisions intended for the British ships on twenty carts, New Yorkers marched through the streets with the confiscated goods until they reached the almshouse and distributed the provisions to the poor.

Crowd action was not the only response, as the city’s Common Council promptly passed anti-British resolutions condemning Britain’s navy’s conduct and raising the common themes of free trade and sailors’ rights, frequently used by Americans against the British from 1793-1815. Members of the Tammany Society, a Republican political club, also took action, holding a meeting where they resolved to unbury the tomahawk to avenge the murder of Pierce. In memory of the dead American, ships in the harbor lowered flags to half-mast and clergy rang church bells to honor Pierce. While further formal protests by Mayor Clinton and President Jefferson were delivered, they had no impact on British naval officers who continued their off-and-on blockade of New York. [2]

Americans were further angered in June 1807, when a British warship Leopard fired on the American warship Chesapeake, off the Virgina Capes, killing three and wounding eighteen Americans. While the British apologized and offered compensation to the families of the men killed or injured in this case — unlike the fiasco in New York Harbor the previous year — they refused to change maritime policy. Failing to win concessions from the British, President Jefferson asked Congress for a trade embargo to pressure the British, which they granted shortly thereafter. Going into effect in December 1807, the embargo devastated the city’s economy. Broadly speaking, it took New York City until 1825 to recover from the impact of the embargo and later War of 1812. [3]

“All Business is at a Stand”: Living Through the Embargo in New York City

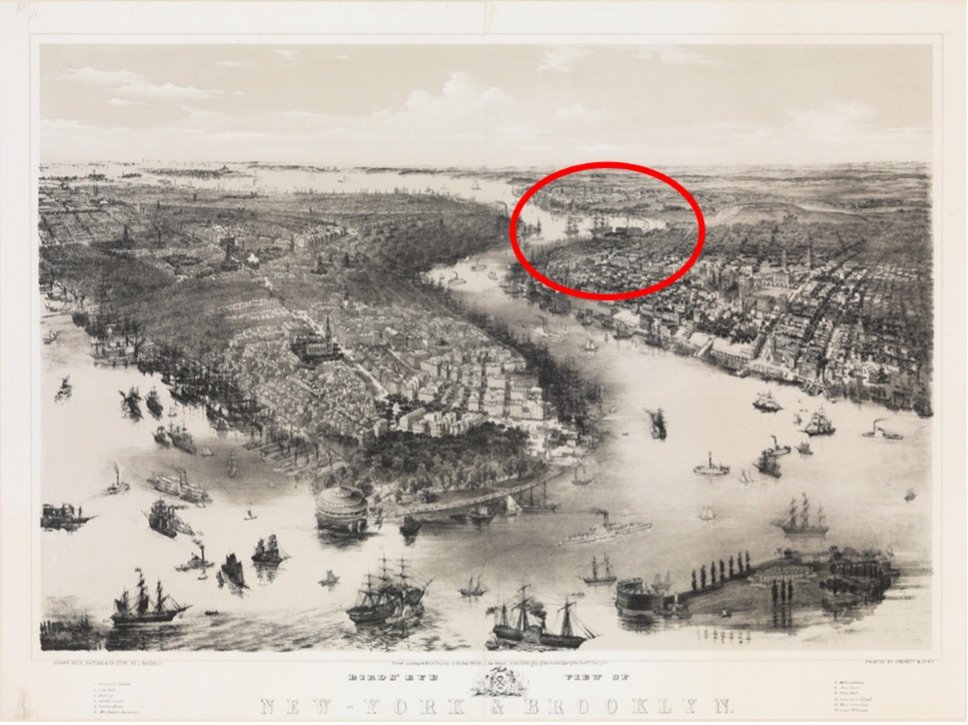

Uncertainty over Anglo-American relations and imposition of an embargo depressed business activity in New York City. Merchant William Rhinelander observed, “All Business is at a Stand.” Banker and merchant Oliver Wolcott, Jr, similarly wrote that the unfavorable condition of public affairs depressed business activity. About 300 ships lay at anchor in New York when news arrived of the embargo on Christmas Day. Immediately, ship owners sent word to their vessels to leave port as soon as possible. In a frenzied effort to depart the city, many ships left half-manned, partially laden, and without government clearance papers. To halt this massive violation of the law, the customs collector dispatched revenue cutters to stop the embargo violators. Gunboats joined in the chase, and some vessels got almost thirty miles from the city before capture. To further stop the mass exodus of merchant vessels, federal officials sent gunboats to Hell’s Gate to prevent ships docked on the East River piers of New York and Brooklyn from escaping into Long Island Sound. Other gunboats were sent to Sandy Hook, New Jersey and the Narrows to block escape into the Atlantic. [4]

A Schooner with a View of New York, 1807. Courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections.

As the merchant vessels hastily fled New York, a crowd of spectators gathered at the city’s wharves to cheer the fleet of embargo violators, reflecting widespread sentiment across the city. As one Federalist editor noted, the embargo “cast a gloom over every countenance.” Many Federalists feared President Jefferson would soon opt for war. Richard Harison, a lawyer and local party leader, observed that the embargo “occasioned great alarm, for fear it would lead to a “fruitless and impolitic” war with England. Coming to the same conclusion, prominent Federalist politician Rufus King remarked that the embargo produced “the most profound alarm,” and he had “never seen as much anxiety and indecision in men of all descriptions.” However, Federalists misread President Jefferson who had no desire to go to war, and the embargo with its economic pressure served as an alternative to war intended to force the British into respecting American neutrality and end impressment. [5]

Regardless of intent, the imposition of the embargo quickly had a negative impact on the city’s economy. William Rhinelander reported that “the great houses of Franklin and Robinson and John Townsend” closed their doors, as did many smaller firms, and by the end of January 1808, nearly forty mercantile houses were bankrupt. There was a “general want of confidence” in the economy, and credit dried up. Over the following months, more mercantile firms failed daily, and a “stagnation of all commerce” developed. Republican David Gardiner admitted, after discussing the economy with twenty other citizens, that merchants “had little else to do than to hover around our fireplaces.” A British traveler John Lambert visiting the city observed “coffee houses were almost empty, streets near the waterside nearly deserted, and grass had begun to grow on the wharves.” Because of the economic depression in New York, merchants and shippers sent a petition to Congress to repeal the embargo. [6]

The merchants were not the only ones who attempted to find redress. Unemployed sailors organized a protest in January. This demonstration against the embargo-induced unemployment alarmed middle and upper-class New Yorkers, and the newly elected Republican Mayor Marinus Willett tried to avoid the embarrassment of a large anti-embargo meeting, fearing it would turn into a riot. When two hundred sailors still came to the meeting, Willett urged them to disperse. Willett emphasized the President ordered the embargo and the jack tars had a responsibility to obey “the captain’s orders” without dissent. [7]

The sailors heeded the mayor’s request, electing a committee to confer with him and the Common Council. As the Council expressed, the sailors considered their situation as “not only distressing but truly alarming.” To pay rent and buy food they went into debt. Not seeking charity, they did not want to accept public assistance at the poorhouse. Being “hearty robust” men they wanted neither public relief nor to be forced to “plunder, thieve, or rob.” As they explained, they simply wanted jobs. Regardless, fearing the sailors might resort to crime, the Comon Council appropriated funds to pay for food, drink, fuel, candles, and rent if the sailors left the city to work in the Brooklyn Navy Yard for the duration of the embargo. [8]

In the early nineteenth century, South Street was filled with merchants’ shops, and the wharves were often lined with ships docked along the shoreline. As a center of employment for working-class New Yorkers, this area was particularly hard hit by the 1807 Embargo. “View of South Street, from Maiden Lane, New York City.” William James Bennett, c. 1827. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Many other New Yorkers also found themselves without work. Besides seamen, thousands of mechanics, and laborers could not find employment. Shipwrights, ropemakers, sailmakers, riggers, caulkers, cartmen, and laborers depended upon their daily wages for subsistence. Fearing the unemployed would turn to crime, city authorities found themselves motivated to do something to alleviate the plight of these working-class New Yorkers. In response, the Common Council created a program of public works, planting trees, and smoothing grounds and vacant lots. Individuals not hired by the city received handouts from the poor house during the winter of 1807 to 1808.

Realizing the potential political danger the jobless might pose, New York’s former governor (1804-1807), Morgan Lewis, wrote Secretary of State James Madison recommending President Jefferson provide employment in the navy yards. As Lewis explained, this might neutralize the Federalist effort to use embargo-created unemployment for their political advantage. Similarly, Republican politician Samuel Mitchell suggested that the jobless could build fortifications around the city, something New York politicians — Republicans and Federalists alike — had been calling for since 1804. [9] Overall, thousands of people obtained food, firewood, and cash from the municipal government, and two voluntary organizations created for the emergency — the Assistance Society and Committee of Forty – also distributed aid to the poor and unemployed. [10]

Regardless of these efforts, the embargo led to a deteriorating economy in the city. During the winter of 1808-09, “hundreds of…honest…and industrious citizens,” of New York City struggled “under the weight “of poverty and distress” produced by the embargo. In 1807, creditors imprisoned 298 people for debt; by 1808 that number had jumped to 1,317. By mid-February 1808, over 5,000 persons found shelter in the Alms House or received daily rations from it. More than a thousand laborers left the city seeking employment in the country, with hundreds of unemployed seamen similarly departing. On January 8th, in a truly radical response to their situation, 150 sailors turned their backs on their nation and accepted passage on British vessels headed for Halifax, Nova Scotia in search of employment in the British merchant marine. All considered, for New York the embargo ranked with the Great Depression as an economic nightmare that caused untold suffering on thousands of its inhabitants unable to find employment and dependent on public charity for subsistence. [11]

“Our voices are for war”: Support for the Embargo

When Post-Master Gideon Granger visited New York a few weeks after the embargo began, he reported to President Jefferson that local Republicans supported the law but lacked the enthusiasm of party members in Philadelphia and Baltimore. Angered at public criticism of the embargo by Federalists, Granger denounced the “aristocrats” of New York City who “are boisterous, insolent, and threatening.” Granger’s concerns were perhaps bolstered by the fact that New York Republicans did not initially unanimously voice support for the embargo. In fact, several New York Republicans, including George Clinton — New York’s populist former Governor then serving as Vice President — seriously worried about the economic impact of the law and the possibility that it would help the Federalists politically. Such concerns were kept quiet, however, with most Republican leaders eventually rallying to support the embargo. Illustrative of this, while sharing similar concerns with his uncle, De Witt Clinton publicly retreated from his early opposition to the law. To show Republican Party unity on the embargo, he chaired a meeting at the long room of Abraham Martling’s Tavern on 18th January that passed pro-embargo resolutions. [12]

Overall, the embargo did win the support — at least publicly — of the majority of New York City Republicans. Some even indicated a willingness to go to war, if necessary, to protect American neutral rights. Better “death to tame submission, insult, and injury,” toasted members of the middle-class General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen. “Our voices are for war,” Mayor Willett bellowed, and proposed to strengthen the military to preserve American independence. Echoing a similar sentiment when speaking to the city’s mechanics, Thomas Haynes asserted the United States would be better off without foreign manufactures. In his view, Europe could not do without goods from the United States, but Americans could live without the rest of the world. As in the 1790s, factions of New York City Republicans staked out a more militant stand on Anglo-American relations than the national government. These statements reflected the intense spirit of American exceptionalism and nationalism that characterized much of New York’s City Republican Party. [13]

New York City Republicans led the nation in Anglophobia. Tom Paine, author of the Revolutionary-era pamphlet Common Sense, hoped “the unprincipled and oppressive” government of Great Britain would “be pulled down.” William Few — a Tammany “Martling-man” activist — prayed the “voice of Justice” would overtake England and destroy “the wicked nation.” Seeking to use public hostility toward Great Britain to counter Federalist opposition to the embargo, Republicans came up with a clever patriotic public relations event. Tammany Society proposed a public commemoration of the Revolutionary War P.OW.’s who died aboard the New Jersey prison ships. Honoring the Revolutionary martyrs, they hoped, would remind New Yorkers of King George’s efforts “to enslave the free sons of America,” and the long British occupation of New York during the Revolution.

Drawing on support from working class laborers, the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, the Coopers, and Hibernian Provident Society, an Irish group, jointly sponsored the new internment of the Jersey dead. [14] On the day of the burial in late May 1808, New Yorkers suspended all business activity. Between 10,000 and 15,000 New Yorkers marched in the procession. Another 30,000 lined the procession route. Veterans of ‘76 carried the thirteen coffins to the burial grounds in the Wallabout section of Brooklyn. While the internment did not take place until May — a month after the 1808 state and congressional elections — Republicans utilized the impending internment to promote Anglophobia and rekindle Revolutionary war memories in support of the embargo. [15]

As a group, Irish Americans in New York City gladly joined in stirring up hostility to Great Britain and support for the embargo. “Let us have war,” toasted Irish American members of the Hibernian Provident Society and the Juvenile Sons of Erin at the March 1808 St. Patrick’s Day festivities. “Paddy is always willing to lend Jonathan a hand” to fight the British was another toast. If the embargo failed, the braves of St. Tammany would willingly “unbury the tomahawk.” More militant than the Jefferson administration, the city’s Irish and Tammany-Martlingmen sought not only public support for the embargo but approval to go to war, if necessary. [16]

The Embargo and Partisan Politics

Fearing urban unemployment would lead to an insurrection at the ballot box, the federal government, state government, and New York City Common Council cooperated in finding food, homes, and employment for sailors. Unemployed laborers obtained jobs with the city as it expanded job opportunities in public works projects. De Witt Clinton proposed spending $100,000 in state funds to build fortifications around New York harbor. When Federalists voted against the use of state funds for the “maintenance of idle Irishmen,” however, Republicans readily accused their political adversaries of insensitivity to the needs of the poor and unemployed. The Federalists would let men starve, Republican editor Charles Holt, observed, “if they are Irishmen.” As Holt chided in a similar vein, the Federalists did not care “if a few hundred Irishmen should die of hunger.” [17]

The embargo’s impact also went beyond local borough politics. It served as the major issue in the 1808 campaign for Congress and state senators and assemblymen; although in New York, Federalists appeals to anti-Irish nativism added a second issue that both groups hoped to use for their political benefit. As editor Charles Holt noted, “the embargo is made the criterion in which the most unimportant popular election is decided. [18]

Heightened political tensions over the embargo also led to violence in the city. For example, a “donnybrook” occurred in late April at a meeting of pro-Federalist sailors. When Cadwallader Colden — Mayor of NYC from 1818-1821 and grandson of the colonial-era Lieutenant Governor — gave an impassioned anti-embargo speech, Republican sailors drowned him out. Pro-Federalist sailors, in order to avoid the “tumult and confusion,” reassembled elsewhere. Meanwhile, the Republican sailors took over the hall and passed pro-embargo resolutions. In retaliation, a Federalist mob marched through the heavily Republican Sixth Ward, carrying an American flag, shouting “no Republicans, down with Jacobins.” [19]

Federalist opposition to the embargo paid off, helped along by Republican disunity. In the state Assembly races, Federalists jumped from twenty-four to forty-seven seats. In 1806, Federalists had won only two of the state’s seventeen Congressional seats. Now they controlled eight. Yet Republicans held firm in the city’s Assembly and Congressional races. In celebrating their victory on April 28th, a mob of 600 Irish-Americans marched down the Sixth Ward, shouting “Kill the Federalist scoundrels.” Further rioting on the night of the 29th led to the deaths of two men. Incensed at the riots, Federalist editor William Coleman accused Mayor De Witt Clinton (once again back in office) for failing to deal with “the mobs and murders in the city.” Blaming the violence on the Irish, Coleman criticized Clinton and Republicans for catering to a “tribe fresh from the bogs of Ireland.” Ironically, as historian Evan Cornog accurately concluded, “De Witt Clinton may well deserve the distinction of being the first big-city mayor to recognize the electoral potential of Irish immigrants and to use policy and patronage to enlist their support.” [20]

Meanwhile, the embargo continued, and in upstate New York widespread smuggling forced President Jefferson to declare the Lake Champlain region of New York and Vermont in a state of insurrection against the federal government on 19th April 1808. Overall, New York City lost out economically as trade from upstate reoriented to Montreal, and the city never made up for all the trade it lost due to the embargo.

Both Federalists and Republicans, therefore rejoiced when it appeared that the Erskine Agreement — the document that repealed the British Orders in Council restricting American trade and authorizing the seizure of American sailors — would be approved in exchange for the embargo’s repeal. [21] In addition, upon hearing the news, Mayor DeWitt Clinton and the Common Council suggested the firing of guns from ships in the harbor and for churches to ring their bells to celebrate the Anglo-American accommodation. While New Yorkers welcomed the Anglo-American reproachment, partisanship prevented their celebrating together as Republicans and Federalists competed to claim credit for the end of the embargo. Republicans met at City Hall Park, and Federalists held celebrations at the Circus. Regardless of who was to blame for the embargo, the long-term economic consequences of it and the later War of 1812 were staggering. It would take until 1825 for New York City’s economy to fully recover. [22]

Harvey Strum is a Professor of History and Political Science at Russell Sage College in Albany, NY where he teaches classes on American history, U.S. government, American Jewish history, and genocide. He has written numerous articles on a range of topics, including recent publications on Jewish women’s organizations in Albany, NY and Canadian relief aid to Ireland during the Great Hunger.

[1] This form of forced conscription into British naval service was often referred to as “impressment.” An American merchant marine was paid about $15-18 per month, compared to $7 British Navy. Higher pay and better working conditions attracted British sailors to American merchant ships. Albert Gallaatin has estimated there were roughly 9,000 British sailors on American ships, approximately one-fifth of the total employed. The British needed seamen because their Navy had 36,000 in 1793 and expanded to 114,000 in 1812. The British claimed the right to seize British seamen and also did not respect American naturalization laws or papers which they also claimed the right to impress. Naval officers generally did not care about rules against American born seamen. If short of men, they readily took Americans including African Americans who suddenly became British.

[2] New York Morning Chronicle, 4, 8 September 1804; New York American Citizen, 4 September 1804; New York Gazette, 28 April 1806; New York Daily Advertiser, 26. 28 April 1806; De Witt Clinton to James Madison, 28 April 1806, Captain Whitby to De Witt Clinton, 30 April 1806; De Witt Clinton to Captain Whitby, 1 May 1806, Thomas Barclay to De Witt Clinton, 1 May 1806, Letterbook 1, De Witt Clinton Papers, Columbia University Library (CU).

[3] Raymond A. Mohl, Poverty in New York, 1783-1825 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 110-112.

[4] William Rhinelander to Philip Rhinelander, 17 November 1807, William Rhinelander Letterbook, 1800-1813, BV. New-York Historical Society (NYHS); Oliver Wolcott, Jr., to Frederick Wolcott, 28 November 1807. Oliver Wolcott Paper, Litchfield Historical Society, Litchfield, Ct.;(LHS); New York Commercial Advertiser, 28 December 1807; New York American Citizen, 24-28. 1807; New York Evening Post, 20-28 1807.

[5] New York Commercial Advertiser, 28 December 1807; Richard Harison to William Bailey, 5 1808, Richard Harrison Letterbook, NYHS; Rufus King to Christopher Gore, 21 December 1807, Rufus King Papers, NYHS.

[6] William Rhinelander to Philip Rhinelander undated, early 1808, Willaim Rhinelander Letterbook, NYHS; David Gardiner to John L. Gardiner, 9 February 1808, Malcolm Wiley Collection, University of Minnesota (MnU); Memorial of Sundry Merchants and Shippers of the City and State of New York,’ 26 January 1808, Committee on Commerce and Manufactures. Papers of the House of Representatives, RG 46, National Archives; John Lambert, Travels Through Canada and the United States of North America in the Years 1806, 1807, and 1808, (London, 1813), I, 239-240.

[7] New York Evening Post, 9 and 13 January 1808.

[8] Peter De Witt to John De Witt, 31 December 1807, De Witt Papers, New York State Library (NYSL), Albany; Petition, 9 January 1808, Box 3173, City Clerk’s Records, Municipal Archives and Records Center, NYC; New York Evening Post, 9 and 13 January 1808.

[9] New York Mercantile Advertiser, 30 December 1807; Morgan Lewis to James Madison, 9 January 1808, reel 10, James Madison Papers, Library of Congress, (LC); Samuel Mitchell to Catherine Mitchell, 20 January 1808, Samuel Mitchell Papers, Museum of the City of New York; Dirck Ten Broeck to Abraham Ten Broeck, 22 January 1808, Ten Broeck Family Papers, Albany Institute of History and Art, Albany.

[10] Mohl, Poverty, 29-30, 104, 138-140; Application and report of the Superintendent of the Alms House, 16 January 1809, Report of the Paupers in the Alms House, 15 August 1808, Statement of the Paupers in the Alms House, 1803-09, Box 3172, City Clerk’s Office, Municipal Records and Archives Commission; New York Commercial Advertiser, 21, 24 January, 8 February 1809.

[11] Peter A. Jay to John Jay, 19 February 1808, Jay Papers, CU Minutes of the Common Council of the City of New York, IV, 8 and 15 February 1808; Morgan Lewis to Jams Madison, 9 January 1808, Madison Papers, LC; Raymond Mohl, Poverty in New York (New York, 1971), 110-112.

[12] Gideon Granger to Thomas Jefferson, 7 January 1808; Thomas Jefferson Papers, LC; George Clinton to De Witt Clinton, 7 January, 13 February 1808, De Witt Clinton Papers, CU; George Clinton to Pierre Van Cortlandt, 7 February 1808. Pierre Van Cortlandt Papers, NYPL; New York American Citizen, 27 December 1807 to 15 January 1808. Factions of the Republican Party, like the Order of St. Tammany, who met at Martling’s Tavern were called Martlingmen and when they later built their own hangout, Tammany Hall, assumed the name of Tammany.

[13] Minutes of the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, 1808, General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen Library; Thomas Haynes to Robert Hunter, 27 December 1807, Robert Hunter Papers, New York Public Library (NYPL).

[14] Thomas Paine to James Monroe, 30 December 1807. James Monroe Papers, LC; William Few to Edward Telfar, 8 October 1807, 000098, Reel 16. Lyman Smith Collection, Morristown National Historic Site, Morristown, N.J.; “Report of the Wallabout Committee,” 8 February 1808, Minutes of the Columbian Order, NYPL; Minutes of the General Society of Mechanics and Tradesmen, 24 February 1808, GSMTL; Account of the Internment of the American Patriots, (New York, 1865), 11.

[15] The Wallabout burial was in a rural section of Brooklyn in May, 1808 near the Navy Yard, but in the 1870s it was decided the interned deserved a better monument and were re-buried at Fort Grene Park with a new monument. David Gardiner to John L. Gardiner, 27 May 1808. UMN; New York American Citizen, 24-28. May 1808; Hezekiah Pierrepoint Diary, 26 May 1808, Box 32, Constable Pierrepoint Papers; NYPL annex; Diary of Asa Eastwood, 26 May 1808, Asa Eastwood Papers, Syracuse University Archives.

[16] New York American Citizen, 19 March 1808.

[17] Hudson Bee, 5 April 1808.

[18] Ibid.

[19] New York Evening Post, 26 April 1808; New York American Citizen, 28 April 1808.

[20] New York Evening Post, 28 April to 14 May 1808; New York American Citizen, 28 April to 14 May 1808; Evan Cornog, Birth of an Empire: De Witt Clinton and the American Experience, 1769-1818, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 82.

[21] The Erskine Agreement was later repudiated by the British ministry, who critiqued David Erskine (British Minister at Washington, D.C.) for making too many concessions to the United States. Initial enthusiasm for the agreement, however, quickly reopened trade between the two countries.

[22] Samuel Mitchell to De Witt Clinton, 22 April 1809, De Witt Clinton Papers, CU; “Glorious News, 24 April 1809,” Broadside, N-YHS; New York American Citizen, 25 April 1809; New York Commercial Advertiser, 25 April 1809.