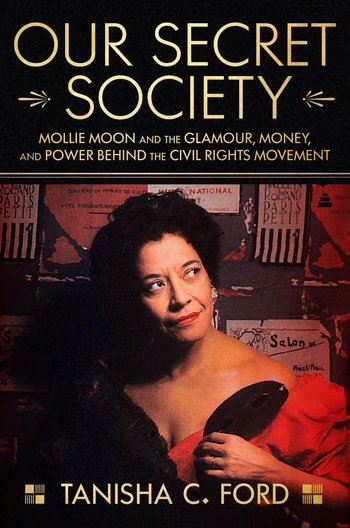

Tanisha Ford, Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, and Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement

Reviewed By Dominique Jean-Louis

If you’re anything like me, when you pick up a historical biography, the very first thing you do is zip your thumb along the page edges, in search of the slight divot of a photo plate insert or two. Especially for a book with “glamour” and “power” in all caps on the cover, the photos in the plate inserts of Our Secret Society: Mollie Moon and the Glamour, Money, Power Behind the Civil Rights Movement by Tanisha C. Ford don’t disappoint. The book’s subject, civil rights strategist and fundraiser Mollie Moon, is the very picture of glamor in each photo she appears in, her hair elegantly coiffed, clothed in either elegantly tailored suits or shining party attire. One can’t help noticing what a regal figure she cuts, whether she’s posing for a portrait or caught in a candid.

But one also can’t help noticing a clue to the “power” that Tanisha C. Ford spends the roughly 300 pages of this book exploring; in nearly every photo, Moon is not making herself the lens’ subject. We see her seated in a group, smiling faintly while reviewing her notes, or smoothing the hair of a partygoer who grins directly at the photographer, or looking sidelong at someone else’s face, as though listening intently. Even in staged portraits, Moon’s favored pose of a smirking sideways glance lends the effect of someone observing the action rather than becoming it. Her intent focus is on something out of frame, sharp eyes assessing. Strategizing. Fixed on something the rest of us can’t see.

Tanisha Ford describes Mollie Moon, and social power brokers like her, as “the glue that connected Black social clubs, church groups, sororities, fraternities, and professional organizations into a national network of contributors who gave of their time and money to keep the movement afloat,” forming a “Black Freedom financial grid [that] established the economic base that supported the frontline activism of Martin Luther King Jr., Fannie Lou Hamer, and John Lewis.” Mollie Moon was perhaps best known for her role as head of the National Urban League Guild, the social and volunteer auxiliary arm of the National Urban League, connecting a national grid of donors, activists, strategists and philanthropists.

Tanisha Ford presents Mollie Moon with both rigorously researched accuracy and generous emotional latitude. In some ways, this book emerges quite naturally from Dr. Ford’s past work. Fans of her past writing on Black women’s sartorial expression will be served well by Ford’s evocative description and analysis of the black-tie events that became Moon’s signature. Especially as Moon becomes entangled in society gossip over her relationship with wealthy NUL donor Winthrop Rockefeller, Ford’s analysis of the pair in their gala getups is a key part of the storytelling. While the book has its fair share of gossip, scandal, and behind-the-scenes infighting, Ford is wise to indulge just enough in the salaciousness, while maintaining a commitment to wider historical context and stakes. So while describing how a photo of the decolletage of a Black woman in a strapless gown next to a wealthy Rockefeller heir captured the imagination of society reporters, Ford is careful to juxtapose this scandal with the story of the shocking miscarriage of justice for Recy Taylor, whose 1944 gang-rape by six white men in Alabama resulted in no legal indictments or charges. Mollie Moon’s glamor and power may have made her grist for the society gossip mill, but she was still a Black woman, and in 1948, the presumption of female sexual innocence was nonexistent for Black women, no matter their station in life.

Ford’s decision to center the financial maneuvering behind and alongside the National Urban League places this book firmly within a long tradition of interrogating money’s relationship to Black politics, as well as a more contemporary cohort of histories investigating Black women’s financial prowess. Much like historian of education James D. Anderson’s foundational The Education of Blacks in the South, or Karen Ferguson’s Top Down: The Ford Foundation, Black Power, and the Reinvention of Racial Liberalism, this book helps to bring to light the role of white-owned philanthropic funds in supporting Black-run civil rights institutions. But Ford’s book also joins more recent works like Banking on Freedom: Black Women in U.S. Finance Before the New Deal by Shennette Garrett-Scott that center Black women’s financial prowess as part of the long tradition of Black movement-building. In public history, there has also been more of a recent emphasis on Black women in the history of business and economics, including philanthropist Madam CJ Walker, bank founder Maggie Lena Walker, and economist Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander.

For readers interested in New York City’s history, Our Secret Society is particularly resonant. Not only will the glittering locales of the Cotton Club and the Top of the Rock become luminously vivid with Ford’s descriptions of the sumptuous fundraisers which took place there, but readers also get a rare glimpse into how the last vestiges of the color line stratified the very substance of New York glamor, and how “old” and “new” money post-war and post-Depression navigated a new era of philanthropy. As Farah Griffin and others have articulated, many Harlem histories jump from the Harlem Renaissance and Great Depression to the Civil Rights Movement. Ford offers not only a bridging of these eras for Black New York, but how the changing tides of leadership, the vacuums and ascendancies of Black leadership worked themselves out in the interregnum.

Even for readers who don’t seek out books on history, this book will hold interest for an audience ranging far outside of other scholars. Ford captures the glittering scenes of Moon’s glamor with absorbing detail- the spectacle she created with her famous Beaux Art costume balls, her youthful adventures with other luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance on film shoot in Berlin, and a behind-the-scenes view of the March on Washington. While a biography of a historically neglected figure is ripe for film adaptation anyway (like Barack and Michelle Obama’s Higher Ground Productions recent biopic on Bayard Rustin), even non-filmmakers may find themselves daydreaming how these characters and vignettes might jump from page to screen.

But before the fantasy casting proceeds in earnest, what we have in this new book is a significant, and significantly fun history of a fascinating individual and a fascinating era that is more than worth the read.

Dominique Jean-Louis is Chief Historian at the Center for Brooklyn History. She holds a PhD in History from NYU.