Remembering George McAneny: The Reformer, Planner, and Preservationist Who Shaped Modern New York

By Charles Starks

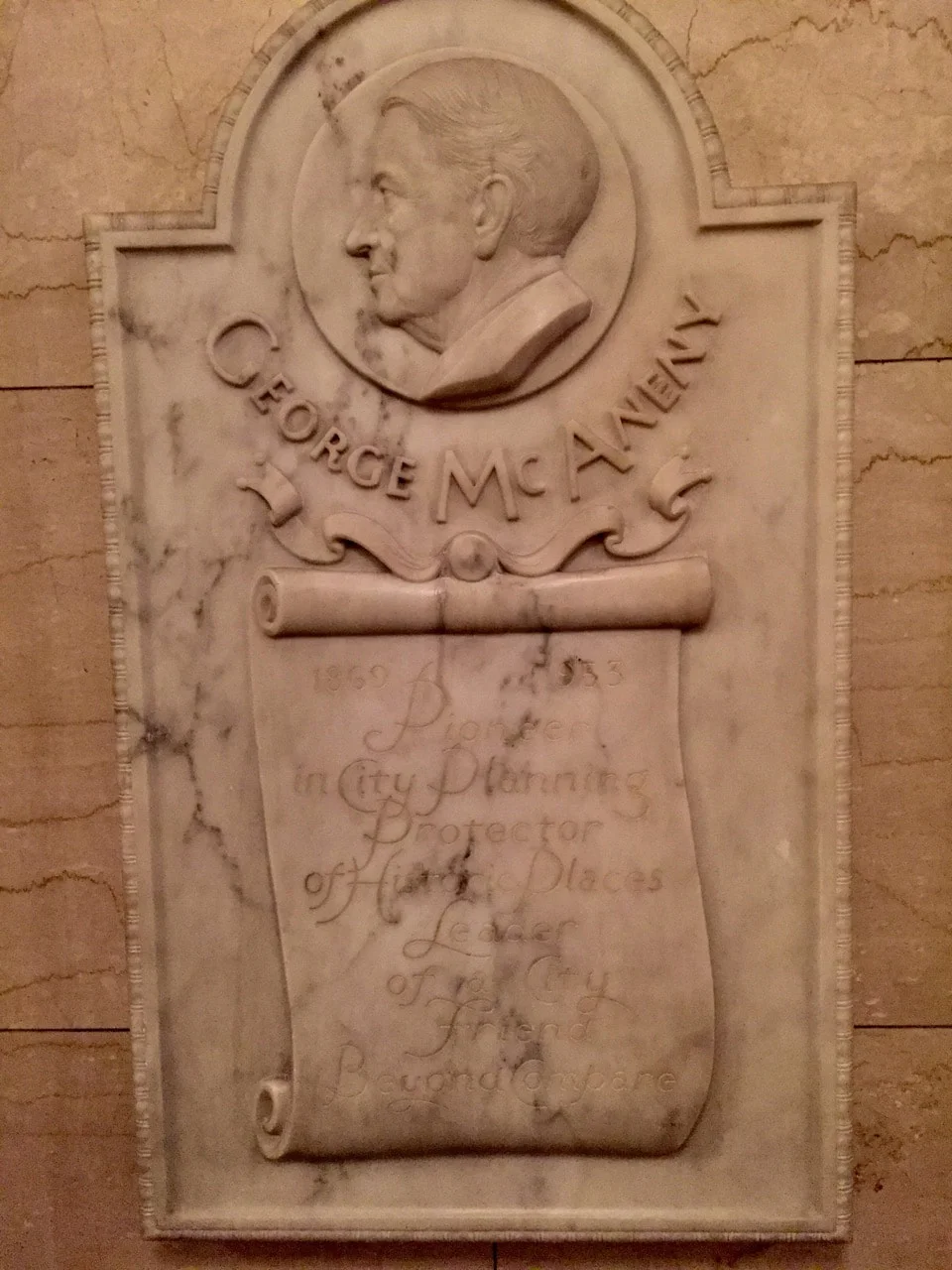

The commemorative plaque in Federal Hall reads “George McAneny, 1869-1953: Pioneer in City Planning, Protector of Historic Places, Leader of a City, Friend Beyond Compare.” It was placed in 1956.

The power to shape the built environment on a metropolitan scale is inevitably shared, contested, and compromised, especially in a city-region as large, diverse, and fragmented as New York has been for the last two centuries. Despite the fervent wishes of more than a few of its leading citizens, the city has never been friendly ground for would-be visionaries seeking to brusquely mold the city’s form to suit their wills—the tech mogul Jeff Bezos being only the latest to find himself chagrined by Gotham’s aversion to imperious planners.

But the city’s history has also been punctuated by figures who were able to mobilize the necessary resources and muster sufficient popular and elite opinion to exert an unusual degree of influence on the form and scale of the metropolis. Though the scope of his power has been somewhat exaggerated, the 20th-century public administrator Robert Moses was unquestionably such a figure. Earlier, in the 19th century, Frederick Law Olmsted and Andrew Haswell Green exerted similar, if less sweeping, influence.

In the first half of the 20th century, New York had George McAneny—a civic leader once so highly regarded as a city shaper that the pioneering city planner George B. Ford called him “the father of zoning in this country” and three years after his death in 1953, he was commemorated with a plaque in the middle of Federal Hall National Memorial, the only individual to be so honored. The plaque is still there today, though most visitors overlook it, and while Robert Moses is virtually a household name in New York, George McAneny is little remembered. If we seek not only to narrate how the city we know today came to be, but also to investigate the different ways in which power is wielded in the metropolis, we might do well to remember McAneny. How is it that a soft-spoken middle-class journalist-turned-public servant was able to be so influential in fields ranging from transportation to land use to historic preservation? And why was he so quickly forgotten?

First of all, George McAneny had a remarkable knack for timing. As a young man in the 1890s, he was the secretary of New York’s civil service reform organization when the dedicated reformer Teddy Roosevelt assumed the governorship; a decade later, he happened to be working for a law firm whose client was the Pennsylvania Railroad at the time it was planning Penn Station; he was elected to office on a reform ticket in 1909 at Progressivism’s peak in New York City, managed to lay low, but remained in public service, during the reactionary 1920s, and returned to prominence in the 1930s, when he helped direct the flows of federal money that were reshaping cities under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. To close his career, he then helped launch the nationwide preservation movement as a patriotic endeavor in the shadow of the Second World War, the destructiveness of which spurred a surge of concern for protecting built heritage.

Secondly, he operated differently from progressive reformers whose careers are better known. Unlike many of his contemporaries in the reform movement, George McAneny did not leave behind voluminous correspondence; archives are full of letters sent to him, but his own voice is frequently absent except in brief replies and copies of prepared speeches and articles. Perhaps many of his letters were lost—a rumor is that his daughter Ruth McAneny Loud, protective of his memory, kept her father’s papers out of public view—but I have come to believe that it is at least equally likely that this was simply a man who was most comfortable—and made others comfortable—with oral communication. How else to explain what a colleague in an anonymous, confidential memo described as “some magic of Mr. McAneny’s” by which his fundraising efforts—he was never a rich man himself—sustained the fledgling Regional Plan Association (RPA) through the Great Depression? And how fitting that such a person was the first figure to sit for an interview, in 1949, at the Center for Oral History at Columbia University. But his style has also obscured McAneny’s importance in the historical record.

On April 30, 1939, the sesquicentennial of George Washington’s inauguration as president in New York City, George McAneny stood on the steps of Federal Hall to proclaim it a national historic site, one of the first urban sites to be so designated.

I began to research George McAneny on behalf of the New York Preservation Archive Project, an organization devoted to documenting the city’s preservation movement. To historic preservationists, McAneny is most well known as the leader who, in the late 1930s and early 1940s, organized successful movements to prevent Robert Moses, in his capacities as a highways and parks administrator, from building a view-blocking suspension span across New York Harbor and then, once the bridge plan was defeated, from destroying Castle Clinton in Battery Park, ostensibly in revenge—stories recounted in Robert Caro’s The Power Broker as the first major defeats for Moses initiatives.

But as I started to piece together McAneny’s career, I began to see him as a much more complex and consequential figure in the history of New York City and of city planning and historic preservation than appeared at first glance. McAneny was an effective leader in the bridge and fort fights because he was, at the time, the president of the RPA, a civic body that was becoming a local and national leader in institutionalizing planning. In fact, the planners and engineers at McAneny’s RPA had an alternative scheme up their sleeve that would actually have been even more destructive than Moses’s plan. Rather than running a bridge across the harbor, the RPA sought to widen the Brooklyn Bridge and build an elevated highway through Chinatown and SoHo. (Fortunately, a cross-harbor tunnel was eventually built instead of either alternative.) George McAneny had also been developing connections within the Franklin Roosevelt administration that would help him not only obtain support to successfully block Moses’s bridge at the federal level, but also to plan the 1939 World’s Fair, direct Works Progress Administration funding to local planning agencies, preserve both Federal Hall and Castle Clinton as national historic sites, and lay the foundation for the National Trust for Historic Preservation, a nationwide body formed after World War II to coordinate federal and regional preservation efforts.

McAneny had become the leader of the RPA, whose original objective was to implement the immense Russell Sage Foundation-funded Regional Plan of New York and Environs, in 1929 on the strength of his earlier accomplishments as an elected official. As Manhattan Borough President from 1910 to 1913—an office to which the city’s charter, in the early 20th century, granted near-mayoral powers—McAneny had been the chief negotiator of the city’s contracts with its subway franchisees to design what was known as the Dual Contracts system of subway lines. The system coupled multiple trunk lines in Manhattan’s business districts with an extensive network of branches to developing suburban locales. The story of McAneny’s transit leadership is best told in Peter Derrick’s exhaustively documented book Tunneling to the Future: The Story of the Great Subway Expansion that Saved New York (New York: NYU Press, 2002).

As the subways began to be built, McAneny was also the driving force behind the city’s 1916 adoption of comprehensive zoning, which was specifically designed to facilitate the concentration of business in Manhattan’s core and spread residential development throughout Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and upper Manhattan. In little more than half a decade, George McAneny’s leadership on the zoning issue, which began when he directed the Board of Estimate to address demands by real estate interests to stabilize the Midtown property market but quickly expanded into a comprehensive regime of land use regulation that addressed the needs of multiple constituencies, gave the city a new pattern of growth that enabled hundreds of thousands of people to ride daily from spacious neighborhoods in the outer boroughs to a core of business buildings that was carefully regulated to permit high density without suffocating overconcentration. The neighborhoods, including places like Jackson Heights, Queens; Inwood, Manhattan; Midwood, Brooklyn; and Bedford Park, Bronx, exemplify what architectural historian Richard Plunz has called the midrise “horizontal city” that dominates so much of the cityscape of New York outside the Midtown and Downtown core.

This horizontal city, with its subway stations, garden apartment buildings, two-family homes, and commercial mainstreets, continues to function much the way McAneny and his colleagues intended it to. As a resident of a McAneny-era neighborhood in Queens and an instructor of CUNY students who live in various parts of the horizontal city and ride the subway to class, I have been surprised at how dimly New Yorkers perceive how their horizontal city was created. Contrary to what many assume, it did not just happen as a result of market forces, nor was it dictated by a single powerful administrator; instead it was the planned result of decisions made by public officials, property developers, and transportation companies whose efforts were coordinated by George McAneny and his colleagues to avoid replicating what they perceived as an unhealthy and financially unstable crowding of people and buildings that had been produced by the laissez-faire nineteenth-century urban property regime. To be sure, not everyone shared equally in the benefits of the horizontal city, and there is little evidence that McAneny paid much heed to the needs of the city’s poorest or its African-American residents, even though he was a lifelong fundraiser for Black educational institutions in the South. But as the horizontal city has matured and served multiple generations of New Yorkers, the adaptability of its design to today’s multiethnic metropolis has become apparent.

As the city looks to a new generation of leadership to confront the critical problems posed by climate change, inequality, and decaying infrastructure amid the ever-present challenges of living together amid extraordinary diversity, it’s worth interrogating how George McAneny and others of his generation shared the power to plan. McAneny provided effective leadership by doggedly working his way into the city’s complex network of civic and governmental institutions and coordinating the pursuit of mutually congruent objectives. This strategy enabled him to exert influence for over five decades, long enough for his impact on the metropolis to become apparent. Sustained engagement also gave McAneny the perspective needed to reflect on the impact of his career and even change his views as he became a staunch preservation advocate late in life.

Ironically, McAneny, who had only a high school education, also did much to instill a culture of expertise into the city’s and region’s urban development practices. In keeping with their early commitment to a merit-based civil service, McAneny and his fellow reformers brought in highly trained experts, including administrators like Robert Moses, himself a Columbia political science Ph.D., and engineers, lawyers, architects, and planners, to apply their professional knowledge to the institutions of civil society and government. Since McAneny’s time, public trust in expert-led institutions has steadily eroded, even as those institutions have demonstrated considerable adaptability and staying power. As contests over this institutional regime continue, both its defenders and its opponents can benefit from closer investigation of the actors, like George McAneny, who were instrumental in shaping it.

In 2019, the 150th anniversary of George McAneny’s birth in 1869, a group of interested New Yorkers and McAneny descendants informally known as the Friends of George McAneny is working with the National Park Service to plan an exhibition at Federal Hall. Details of the initiative can be found atgeorgemcaneny.com.

Charles Starks is a Ph.D. student in city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania and teaches urban studies at Hunter College. He is the author of an online monograph, New York’s Pioneer of Planning and Preservation: How George McAneny Reshaped Manhattan and Inspired a Movement.