The 51st State: Norman Mailer, Jimmy Breslin, and the Politics of Imagination

By Gabe S. Tennen

Mailer-Breslin campaign button, 1969. Museum of the City of New York.

It was early April in 1969, and Norman Mailer, holding court on the top floor of his Brooklyn Heights brownstone, was in his element. Surrounding the forty-six-year-old author, social commentator, and rabble-rouser were an array of the city’s writers, activists, and politicos, and, probably to the liking of the notoriously egotistical Mailer, the topic of the night concerned him.

Gradually, the gathering’s siloed discussions coalesced into a single dialogue, and the group focused their agenda on two questions: Should Mailer run for mayor of New York City? And, if so, could he possibly win?[1]

Mailer was never one to diminish his own potential in areas outside of his expertise. The Brooklyn-raised provocateur had toyed with the idea of running for mayor in 1961, before New York crashed down from the heights of its post-World War II boom.[2] Eight years later, New York was no longer the metropolis the author had imagined leading in earlier that decade. The nation’s largest city was losing population and jobs, and faced a new reality of municipal strife and street-level tension. With the city’s fortunes dwindling, glitz and glamor had given way to conflict and crisis.

Mailer and his intellectual cohort believed that he possessed a much-needed quality lacking in his potential rivals. To deliver Gotham from the grips of tumult would take imagination. After heated debate over Mailer’s credentials, the room came to an agreement. Jimmy Breslin would join Mailer and run for City Council president. As a running mate, the forty-year-old Queens-born journalist, an Irish Catholic from a lower-middle-class household, would balance the ticket, and attract his coreligionists from similar neighborhoods to a candidacy headed by the Jewish, brainy, and unapologetically inflammatory Mailer.

On May 1, 1969, the two entered their names in the Democratic primary election for mayor and city council president. [3] Their campaign promoted radical solutions to the issues facing the five boroughs, advocating decentralization and local control. This cause célèbre lined up with a movement taking place across the five boroughs. Mailer and Breslin took that trend several steps further, deciding that New York City should become the fifty-first state of the union, with each of its unique neighborhoods becoming its own municipality. [4] Their platform became known by a simple shorthand phrase: “The 51st State.”

Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin campaigning in the Garment District, June 1969. The two sometimes verbally sparred with voters at events like these, ultimately alienating potential supporters. New York Times.

During their campaign, Mailer and Breslin applied their unorthodox thinking and provocative language to the problems facing New York in the late-1960s. An examination of this venture illuminates a juncture in the urban experience of the United States that required creativity and a departure from exhausted policies. In the following years, the city would continue to face obstacles, culminating in the 1975 financial crisis and the city’s narrow avoidance of bankruptcy. For a brief moment, however, the 51st State’s political reinvention offered another route entirely.

The Mailer-Breslin campaign framed their idea for city-statehood as a means for New Yorkers to take power into their own hands. The candidates argued that Gothamites had to seize control of their destiny by wresting power from upstate and federal politicians who were indifferent at best, or hostile at worst, to their city. Breslin decried the distance between city dwellers and those governing them: “The business of running this city is done by lobster peddlers from Montauk and old Republicans from Niagara Falls and some Midwesterners-come-to-Washington-with-great-old-Dick such as the preposterous [Secretary of Housing and Urban Development and former Michigan governor] George Romney.”[5] In order to overcome pervasive anti-urban sentiment, the campaign suggested removing anti-urbanites from the decision-making process altogether.

The two were correct that the city received short shrift from both the state and federal governments. The city paid the sum of almost $20 billion in taxes to the United States government in 1968, while receiving only $7.1 billion in federal expenditures. State residents outside of the five boroughs, however, due to an aggressive congressional delegation and friendly representation in Albany, collected $19.4 billion in federal funds after contributing a total of approximately $30 billion. City-statehood, the Mailer-Breslin campaign contended, would increase bargaining power for the city, stabilizing local budgets while allowing the five boroughs to recoup more of its tax dollars for needed investments.[6]

While the city was denied its fair share of federal funds, the state also reaped hefty profits from its stricken downstate metropolis. In 1968, the five boroughs provided $2.5 billion to Albany’s coffers for, according to the 51st State team, “the privilege of electing one governor, two senators, ninety-four legislators, and an assortment of other state officials.” Only $1.385 billion of that contribution ever made its way back downstate. The 51st State would offer over $1 billion in net savings, the campaign estimated, by removing itself from New York State, providing a serious financial boon to the cash-strapped city of New York.[7]

Mailer and Breslin inserted themselves into an already chaotic municipal primary season. On the Republican side of the aisle, Mayor John V. Lindsay faced an uphill battle in his quest to secure his party’s nomination for a second time. Though he originally entered office in 1966 accompanied by a wave of enthusiasm, Lindsay’s tenure was defined by recurring labor unrest and increasing tension in the city streets, leading to wide disillusionment with the policies of the young mayor.[8] Conservative State Senator John J. Marchi, hardly known outside of his borough of Staten Island, challenged Lindsay in the Republican primary, leading to the possibility of the incumbent’s ouster from his own political party.

Mailer himself was less than enthralled by the prospect of another Lindsay term. “If you give the Honorable John two more years,” he mused while campaigning, “there will be only two things left standing in New York – a photographer and the Honorable John, posing for pictures with his hair blowing in the wind.” The author maligned Lindsay’s incremental approach to the city’s problems, particularly with regards to his piecemeal programs of community control. “I don’t believe in gentle progressive steps. This city is half insane by now and we have to do something.”[9] Like many others in the city, Mailer had grown weary of Lindsay’s perceived inaction. He wanted an abrupt change.

Similarly, the 51st State team portrayed their Democratic opponents as more of the same. That race featured former mayor Robert F. Wagner, who served from 1953 until 1965; city comptroller and conservative machine politician, Mario Procaccino; Bronx Borough President and liberal favorite, Herman Badillo; and little-known United States Representative James H. Scheuer.[10] Those career legislators were forced to contend with the acerbic wit of Mailer and Breslin. Describing his competition, Breslin opined that “the reason we got into politics is that we knew the one thing we could do better than the other politicians is to lie. At least that’s what we thought. But we found out we were hopeless amateurs.”[11] The two continued to verbally pummel their fellow Democrats throughout the primary season.

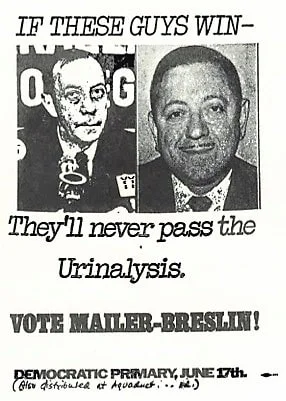

Sardonic advertisements like this one, picturing former mayor Robert F. Wagner and comptroller Mario Proccacino, reveal the how the 51st State team really felt about their competition. Campaign flyer, from Running Against the Machine: The Mailer-Breslin Campaign, 1969.

If the language Mailer and Breslin employed seemed idiosyncratic, the issues they addressed represented common concerns across wide swaths of New York City’s citizenry. The campaign published detailed position papers on education, housing, transportation, crime, air pollution, and other issues. In each case, they used the 51st State as a foundation on which to build their ideas. Their proposals offered a comprehensive vision of local rule, with, for instance, each city neighborhood forming its own school district and police department. The campaign also employed nostalgia for a city disappearing amidst the changes of the 1960s. A neighborhood world series of stickball, banning all private automobiles from Manhattan, and free bicycles for all city residents were each suggested as means to return the city to its halcyon days.[12] Mailer and Breslin wedded their political philosophy of self-determination to a romanticized vision of the city of their youth.

Education was one issue that that the Mailer-Breslin campaign seized as a perfect example of how statehood could benefit New Yorkers. 1968 marked a cataclysmic moment in the city’s public schools. A series of teacher’s strikes, punctuated by a thirty-six day citywide walkout that September, exposed growing rifts in New York’s social fabric and called to question longstanding notions about the role of the city’s education system.[13] In response, Mailer and Breslin offered both penetrating language and policy proposals they believed would strike at the heart of that institution’s disorder.

Even more sweeping, they argued that fixing schools would begin to repair New York as a whole. “We don’t have oil wells and crops in New York,” Breslin told reporters in May. “We produce people. We’re wasting our only product, which is people.”[14] Schools were the city’s best chance to create that human capital, but instead they were constituted as pipelines to prison. “For the…years ahead, the kids of the ghettos are our treasure. And we are spilling our treasures across the floors of the criminal courts buildings.” According to the candidates, New York’s education system had become an incubator for the city’s problems writ large, but the 51st State could begin to resolve that issue.

The candidates first addressed the school system’s finances. Through statehood and the creation of individual municipalities, the city-state would administer funding to schools on a per-capita basis, with additional allocations made available for underprivileged areas. Albany, which contributed 38.8 percent of the system’s budget and dictated education policy from miles upstate, would be removed from the equation entirely. The new city-state, in turn, would exercise increased bargaining power with the federal government, ultimately helping to raise the federal contribution to New York’s education system from 6.1 percent to an even fifty-fifty split. Finances would be freed to address other issues like capital improvements and investments outside of administrative functions.

The campaign outlined forms of oversight and planning to replace the centralized power of the Board of Education. In the 51st State, the Board would instead function in an advisory capacity, as each neighborhood constructed its own school system from the ground-up. Local school boards would decide on staffing, curriculum, testing, and everything in between. The United Federation of Teachers (UFT), the city’s educators’ union, would be broken into smaller organizations representing each local school district to discourage future citywide strikes. This restructuring, the candidates argued, would offer New Yorkers the chance to determine their children’s fate without the heavy-hand of an uncaring and culturally distant bureaucracy.[15]

Mailer and Breslin blamed lawmakers in Albany for the school system’s frustrations. “The 1968-1969 school year has been a wound,” Breslin wrote before listing abysmal statistics about graduation rates, grade projections, and segregation. State lawmakers lived in suburban or rural villages like Montauk, Niagara Falls, and Peal River. “The schools and the pupils are in places they never see, East New York and the South Bronx,” Breslin wrote. These “white politicians pressured by [UFT President] Albert Shanker…feel their responsibility to the city begins and ends with road building.”[16] For Norman Mailer and Jimmy Breslin, troubles in city schools encapsulated the larger issues pressing New York during the late-1960s. The 51st State platform would not only offer true community control over education, but would also, beginning in the classroom, help to heal the city as a whole.

The campaign employed colorful imagery to highlight the unique character of each New York City neighborhood. In the 51st State, those neighborhoods would become their own individual municipalities. Abe Gurvin, "New York City: The 51st State", 1969. Library of Congress.

On June 17, 1969, New Yorkers went to the polls to cast their ballot in that year’s primary elections. On the Republican side, Lindsay was defeated by Marchi, forcing the incumbent, who was eventually victorious in the general election, to run on the Liberal Party ticket. In the Democratic primary, Procaccino, described as the embodiment of bankrupt Democratic machine politics by the Mailer-Breslin campaign, garnered 233,486 votes, earning him the nomination for that year’s general election. Trailing well behind him was Mailer with 39,209 votes. Breslin’s 65,659 votes in the race for City Council president also landed him in the second-to-last spot. United States Representative and future governor of New York, Hugh L. Carey earned the Democratic nomination for that position with 135,785 votes.[17]

In spite of their dismal performance in the polls, Mailer and Breslin changed how some New Yorkers viewed their city’s future and potential. Writing in the Village Voice later that month, Richard J. Walton described the significance of the campaign as more substantial than an ignominious defeat at the polls. “We have had essentially liberal government nationally and locally ever since [Franklin D.] Roosevelt was first elected in 1932 — and look at our society,” the author opined. “Liberals have often been ineffective, doctrinaire, intellectually flabby, corrupted by power and their still unassailable belief in their own superiority, and all too often cowardly.” That impotence was the thrust behind Mailer’s campaign. Walton described Mailer as “imaginative, intellectually tough, wary of power, and brave.” Mailer “recognized the bankruptcy of liberalism and, unlike most of us, was in a position to undertake a significant campaign against it.”[18] The 51st State campaign acknowledged that the issues faced by New York in the late-1960s required a profound reinterpretation of the politically possible in American urban politics. Beneath their bluster, Mailer and Breslin offered a serious and important reconceptualization of what a city was and how it could function.

The turmoil in New York City and across the United States in the late-1960s provided the fertile ground from which the idea of the 51st State sprouted. In the candidates’ inimitable fashion, they each responded to the unique conditions of that era in a meaningful way, offering the wholesale transformation of New York City as a means to lift the city from decline. The 51st State, though, also has important implications for today, when the governor of New York and the city’s mayor engage in public battle and the federal government threatens to punish the five boroughs for their perceived misbehavior. New Yorkers, and urbanites everywhere, would still do well to heed the words of Mailer and Breslin: Power to the neighborhoods!

Gabe S. Tennen is a PhD student in History at Stony Brook University.

Notes

[1] Jimmy Breslin, “I Run to Win,” The Village Voice, May 5, 1969.

[2] Mary Nichols, “Norman Mailer’s LEGO Vision of New York,” The Village Voice, Feb. 18, 1965.

[3] Flaherty, 57.

[4] Flaherty, 21-23

[5] Breslin, “I Run to Win.”

[6] Whit Smith and Peter Manso, “Position Paper: City-State Finances,” qtd. in Running Against the Machine, 204-205.

[7] Smith and Manso, 202-203.

[8] Vincent J. Cannato, The Ungovernable City: John Lindsay and His Struggle to Save New York (New York: Basic Books, 2001), 11.

[9] Jane O’Reilly, “Diary of a Mailer Trailer,” qtd. in Running Against the Machine, 286.

[10] Cannato, 403-415.

[11] Betty Flynn, “Mailer and Breslin: An Odd Couple,” The Journal News(White Plains, NY), Jun. 12, 1969.

[12] “A Miscellany of Ideas for the 51st State,” qtd. in Running Against the Machine, 212-214.

[13] Jerald E. Podair, The Strike That Changed New York: Blacks, Whites, and the Ocean Hill-Brownsville Crisis (New Haven and London: Yale University Press).

[14] William Reel, “The Bore Buster,” The Sunday News, June 1, 1969, qtd. in Running Against the Machine, 124-131.

[15] Clifford Adelman and Peter Manso, “Policy Paper V: Education,” qtd. in Running Against the Machine, 178-191.

[16] Jimmy Breslin, “Running Other Peoples’ Lives,” The City Politic, Apr. 21, 1969, qtd. in Running Against the Machine, 17-20.

[17] “Primary at a Glance,” The New York Times, Jun. 18, 1969.

[18] Richard J. Walton, “Impossible Choices: Why Mailer Ran,” The Village Voice, Jun. 26, 1969.