“Selling Service” and “Venting Your Spleen”: Anti-Vice Policing in WWII NYC

By Emily Brooks

A Spring 3100 cover from May 1943 depicts an NYPD officer assisting an individual who is weighed down with goods for his victory garden across the street. Both the officer and the gardener are presented as performing patriotic duties, with each "doing his bit."

In the transcript of a speech that appeared in the April 1943 issue of Spring 3100, the New York City Police Department’s internal magazine, District Attorney Frank Hogan advised the city’s police officers that, “your work was never more important than it is now.” Hogan stated that policing the city was a central part of protecting the members of the armed forces who may be passing through its streets during WWII. Hogan noted “if a soldier gets in trouble and must appear in our courts as witness, complainant, or defendant, valuable days of training and of service are forever lost with possibly fatal consequences to someone fighting in our cause.”[1] New York’s Mayor Fiorello La Guardia had also informed officers the year before that, “Ordinarily, in normal and peacetime conditions, you would be wholly officers of the City of New York but now every one of us, you and I, in addition to our responsibilities as officer of the City of New York are also part of the great National Defense forces of our country. As police officers you are just as much in the service of your country as you would be were you in the uniform of the Army or the Navy.”[2] According to La Guardia and Hogan, enforcing the city’s laws was now an issue of national importance and not merely one of local urban order.

La Guardia and Hogan, joined by Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine, presented anti-vice policing as an essential component of protecting the nation through controlling its urban populations. These local power players argued that the city had to be protected from prostitutes or “lone women” seeking to prey on the sexual desires of servicemen, and from “the guerillas, the racketeers, the hoodlums, and the gangsters” who might tempt or threaten the moral and physical safety of servicemen in other ways.[3] Police officers were tasked with determining which New Yorkers embodied these threats, and they possessed extensive power over how to make these determinations. An examination of public statements, procedural manuals, arrest records, and internal documents related to policing from this period suggests that NYPD officials and local politicians encouraged officers to use visual and geographic clues that they associated with race, class, gender, and sexual orientation to first discern supposedly deviant people and only then to arrest these individuals for a criminal act. In this process, police officers, as agents of the state, created meaning about criminal categories by targeting, beating, and arresting some New Yorkers, while assisting or ignoring others. Officials like La Guardia and Valentine justified this activity through new language of wartime nationalism, and devoted additional personnel to controlling vice, but did not meaningfully extend the significant powers already enjoyed by officers when monitoring for these crimes. In New York City, the mobilization for war drew more energy and attention into anti-vice policing, and thus renders the extensive powers that officers had already possessed to discern and label deviancy more visible.

Campaigns against prostitution were a key component of anti-vice policing. Prostitution had been a longstanding concern for police and politicians in New York, but it was invested with new meaning in the late 1930s as U.S. entrance into WWII appeared more likely. In these years and into the 1940s, local law enforcement officers and politicians, as well as national officials in newly formed federal agencies like the Social Protection Division (SPD), became increasingly concerned with the moral and physical health of young men. These officers worried that male servicemen would be infected with venereal diseases through sexual activity with prostitutes or single women, and thus be rendered unfit for service. In propaganda materials produced by the SPD women were presented as carriers of venereal diseases, while men appeared as their unwitting victims.

As the U.S. mobilized for and then entered the war many officials saw prostitution as a dangerous threat to the nation’s male population and thus to national strength. In February of 1942, the Commissioner of the NYPD, Lewis Valentine, established a new unit within the department devoted to the suppression of vice in areas near military and naval establishments and in districts visited by soldiers and sailors on leave, with a particular emphasis on prostitution and gambling.[4] Mayor La Guardia stated of the connection between war and prostitution, “The question of prostitution in connection with war is not new…We have our normal problem, and the war brings an additional one. There we need the full and complete cooperation of the Army and the Navy.”[5] To this end, the mayor encouraged more anti-vice policing from the NYPD, and publicly backed the May Act, federal legislation to criminalize vice near military and naval establishments.[6] The May Act permitted a federal take over of anti-vice policing in designated areas, if efforts of local law enforcement were deemed wanting. The act, however, was only used twice, once in North Carolina and once in Tennessee, and never in New York.[7] The NYPD, therefore, maintained control over policing prostitution in New York.

A cartoon featured in Spring 3100's "Kop Komiks" section, which ran cartoons submitted by members of the NYPD, depicts an officer surveying a sailor and a woman seated together on a bench. The officer views the seated pair with interest, while the sailor attempts to distract his attention. The image, which appeared in the magazine in July 1944, plays on the way officers were encouraged to monitor socializing between single women and men, particularly enlisted men. "Kop Komiks," Spring 3100, July 1944, 31.

The same concerns that led to the May Act drove public figures to express anxiety that prostitution and general female promiscuity was becoming more widespread. Officials used new anxieties about “pick-up girls,” or women who supposedly chased servicemen for some combination of sex, fun, and money, to justify reframing and expanding preexisting policies to restrict female autonomy. In the summer of 1942, Police Commissioner Lewis Valentine ordered uniformed officers to repeatedly visit every bar and grill in the city and to report locations to the Alcoholic Beverage Control Board for censure if they harbored “lone women.”[8] This practice represented a wartime take on policies that had been used to control behavior in bars and restaurants since the repeal of alcohol prohibition in 1933. The regulations created after repeal permitted the State Liquor Authority to revoke the licenses of establishments that harbored “undesirables,” including prostitutes, gamblers, gay men, or lesbians. In the language of the regulations the presence of such individuals rendered an establishment “disorderly.”[9] During the war similar policies were reframed and given more official backing as part of an effort to protect male troops from sexually active women.

Two years after Valentine’s effort to censure establishments for the presence of single women, official attention was still aimed at this female threat. In a 1944 article entitled “Police War Urged on the Pick-Up Girl,” the New York Times indicated the tenor of that year’s conference of the New York State Association of Chiefs of Police, which addressed, among other topics the “new hazard” of the “pick-up girl.”[10] Local officials led by Mayor La Guardia encouraged the NYPD to police crimes of prostitution more aggressively because of the mobilization for war. Officers of the NYPD, however, had already possessed significant freedom to identify problematic women and label them as prostitutes. The testimony of police officers required no corroborating witness in prostitution cases, and was usually accepted by the magistrate without challenge. Police officers were often the only witness to testify against women arrested for prostitution. [11] Officers, therefore, had significant liberty when arresting women for prostitution, both before and during the war years. The policies publicized to deal with the “pick-up girl” were a more widespread form of the same powers officers had possessed before the war.

The NYPD did not police all women for these criminalized behaviors in the same ways, however. In a meeting of seventy-five uniformed and detective commanders who gathered to discuss the latest issues facing the NYPD in August of 1942 Commissioner Valentine highlighted prostitution as a central problem facing the department and the city. The Commissioner reminded his subordinates, however, not to harass “innocent women,” while also encouraging them to suggest that officers invoke laws against loitering and vagrancy “if it was too difficult to get conclusive evidence of prostitution.”[12] These comments indicate that to Valentine, policing prostitution meant monitoring women, but that some women were presumed innocent and should not be bothered, while others were guilty even if conclusive evidence of prostitution could not be obtained.

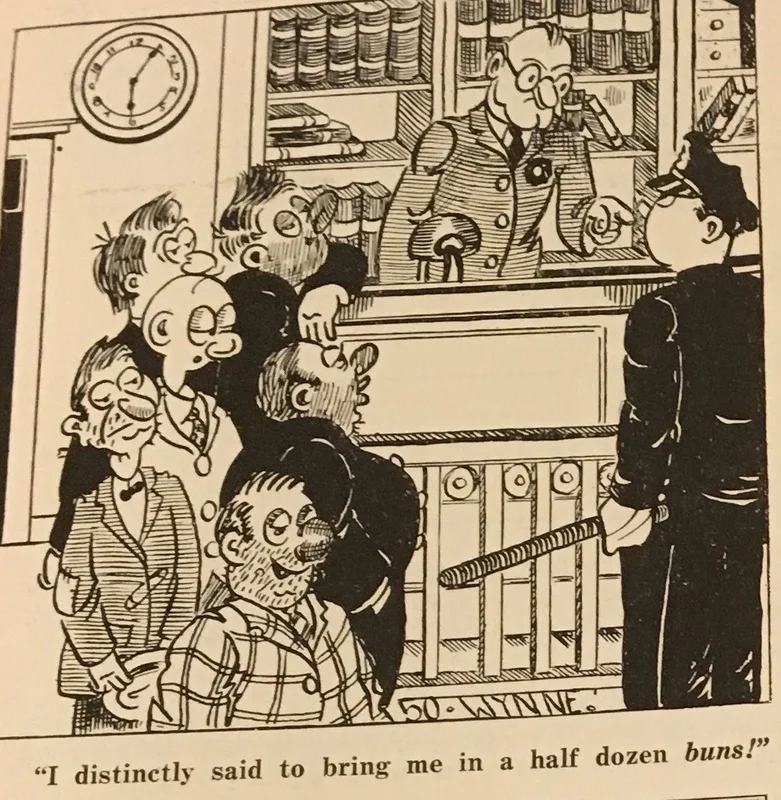

An illustration in the "Kop Komiks" section from the October 1942 issue of Spring 3100 includes a joke about an officer who confuses "buns" and "bums." The comic relies on a pun, but also makes an implicit statement about the ease with which officers could seize men off the streets of New York City. "Kop Komiks," Spring 3100, October 1942, 26.

How then, were officers to determine who should not be bothered and who should be arrested even without conclusive evidence? The Policewoman’s Handbook, which was published in 1933 but remained popular with police departments for decades after its publication, provides some insight into how policewomen patrolled for suspected prostitutes.[13] Policewomen were particularly charged with patrolling women and children. The author, who served as chief of the Detroit Police Department’s Women’s Division for over a decade, advised policewomen on patrol that, “the girl or woman who is a prostitute may sometimes be identified by her slow pace, or gait, and apparent lack of destination, by her dress, which is usually conspicuous and often out of place, by excessive make-up, etc. Her attitude often shows lack of interest in anything but her objective of securing a man.” The handbook goes on to remark that, “occasionally the young prostitute is very modestly and correctly dressed and may only be detected by her conduct.”[14] This description indicates that a wide variety of behaviors could be read by patrolwomen as signifying prostitution. Poor women whose clothing would have been more likely to appear disorderly or inappropriate to the area, season, or time of day, and who would have been more likely to spend time in public spaces, would have been at increased risk of arrest.

Although the author does not mention race as a factor that patrolwomen should consider when looking to make arrests for prostitution, the statistics indicate that black women were disproportionately arrested for prostitution. In a report on prostitution produced by the Welfare Council of New York City in 1941, the author noted that 54 percent of the arrests for prostitution in the years surveyed were perpetrated on black women, despite the fact that they comprised only 4.7 percent of the city’s population. The author even commented on these statistics, stating “no one could have read the findings of this study without being struck by the facts that (1) Negro women are arrested in great disproportion to the ratio of white and Negro in the population.”[15] This disparity suggests that the NYPD targeted black women, black neighborhoods, or some combination between the two when making arrests for prostitution.

Protecting the nation from vice in New York involved more than regulating women under anti-prostitution laws. While preventing prostitution provided justification for monitoring women, the NYPD also ramped up their policing of men for gambling related offenses. In September of 1942, La Guardia demanded of Commissioner Valentine and two hundred other department executives, “I want all forms of gambling wiped out. If you don’t clean up this situation I’ll clean you up.”[16] He also advised officers how to handle “tinhorn gamblers” that they might encounter on their beats. The Mayor stated of such “tinhorns,” “if you see him on your beat, sock him on the jaw. I’ll stand back of you.”[17] This statement from La Guardia reveals, in addition to an embrace of police brutality, that the presumed gender of “tinhorn gamblers” was male. In the raids that the NYPD began in the days following the mayor’s orders fifty-eight men were arrested for “using loud and boisterous language,” “bookmaking,” or “violating the gambling laws.”[18] When the raids were concluded over 600 arrests had been committed for gambling related offenses, including “obstructing sidewalks while looking over racing sheets.”[19] The expansive nature of the descriptions of offenses suggests that, as in the case of arrests for prostitution, NYPD officers had significant freedom over how to identify problematic people and places in the city and then to perform raids and apply gambling-related criminal categories to them.

How the NYPD made these distinctions for gambling related arrests is less accessible than details on prostitution, since the NYPD annual reports from the period only breakdown arrest data by gender, but some evidence suggests that race played a significant role. Professor E. Franklin Frazier of Howard University’s 1935 study of social and economic life in Harlem, however, provides some insight into the policing practices of officers from the seven precincts that operated in the neighborhood. Frazier examined arrests records in these precincts over the first six months of 1935, and determined that of the male arrests, 31.9% were for policy gambling and another 30% were arrests for disorderly conduct.[20] These statistics suggest that a significant amount of the policing performed in Harlem, a predominantly black neighborhood, in the mid 1930s was justified through supposed controlling of vice. Harlem also received attention in the gambling raids that La Guardia ordered in 1942, with Valentine promising to send additional officers to the neighborhood “if forces already assigned were insufficient.”[21] African American Harlem residents were also interviewed about their feelings toward the police in 1943 after an incident of police brutality on August 1st led to days of unrest in the neighborhood. Many residents expressed anger and frustration at the treatment they received by officers of the local precinct, whom one respondent describes as “drunkards and thieves.”[22] When NYPD officers were identifying the “tin-horn gamblers” on their beats, therefore, it seems possible that they may have disproportionately targeted black men.

La Guardia, Valentine, and other local players in politics and law enforcement encouraged officers of the NYPD to use a different approach to treat the city’s supposedly non-problematic residents and visitors. In a speech reprinted in Spring 3100’s May 1940 issue, Valentine encouraged his officers to “vent all your spleen” and to be “rough, tough, disagreeable and obnoxious” to “the guerillas, the racketeers, the hoodlums, and the gangsters.” The Commissioner assured his law enforcement audience that after doing so “you will be commended, never fear.” In the same speech, however, the commissioner also directed officers, “don’t drive into court, for trivial violations, reputable, decent, honest, and hard-working people.” [23] In these statements Valentine encourages two separate approaches for policing in the city, one characterized by consideration, courteousness, and leniency, and the other by harassment, violence, and violation of civil rights. When dealing with “respectable” residents Valentine begged his officers to remember they “should be selling service” but when interacting with those labeled “hoodlums,” “guerillas,” or “prostitutes” a lack of a clear violation of the law was not to be considered an impediment to making an arrest or implementing a beating.[24] Officers of the NYPD, therefore, were tasked with determining which form of policing to use when, and they were encouraged to use arrests for crimes of vice as a means of controlling undesirable residents or visitors.

In March of 1942 an author writing in Spring 3100 discussed changing arrest rates for the years 1940 and 1941, and reflected on what these statistics revealed about the department’s anti-vice policies. The author lauded a decrease in “major crimes,” during this period. He also noted, however, that arrests for “prostitution and commercialized vice” had increased 13.8 percent.[25] The author expounded on this increase, musing, “that the number of such offenses as are recorded are almost inevitably co-existent with raids upon these offenders.” He continued, stating that, “an increase in the number of offenses reported for these crimes is more indicative of police activity than it is of the actual incidence of the crime.”[26] In this attempt to diffuse concern about an increase in arrests for prostitution and gambling, the author articulated an idea that scholars of policing and advocates of police reform have presented, but that police departments rarely publicize themselves. He noted that the arrest records of New Yorkers in 1940 and 1941, particularly those arrested for crimes categorized as vice, may reveal more about the practices of the NYPD than the habits of those they policed. Arrest records from the late 1930s and early 1940s, as well as official language from leaders in the department and the city, suggest that NYPD officers used anti-vice laws to control undesirable New Yorkers. In this process of controlling urban people and spaces, law enforcement officials and officers invested criminal categories with information about gender, race, and class. As they targeted and arrested particular people for prostitution, gambling, and other vice offenses NYPD members defined these criminal categories in part through gender, race, and class. In this process police officers wielded immense power to determine whom to monitor, coerce, arrest, and assault. Local officials and politicians invoked wartime nationalism to justify these activities, creating a new language to support a reinvigoration of preexisting policies. La Guardia and Valentine encouraged officers whom they described as “just as much in the service of our country as men in the armed forces,” to first differentiate between respectable or problematic New Yorkers, and then arrest or assault the latter, while assisting and serving the former.[27]

Emily Brooks is a PhD Candidate in History at The Graduate Center, and a CUNY Humanities Alliance Fellow. Her dissertation focuses on anti-vice policing and gender in New York City in the 1940s.

[1] Frank Hogan, “Law Enforcement…Then and Now: An address delivered at the Communion Breakfast of the Police Department Holy Name Society,” Spring 3100, April 1943, 10.

[2] Mayor La Guardia, “Appointments to the Department,” Spring 3100, April 1942, 5.

[3] “Army, Navy Spur Vice Drive Here,” New York Times, August 11, 1942, 14. “3,000 Attend St. George Breakfast,” Spring 3100, May 1940, 6.

[4] “Police to Safeguard Service Men in City,” New York Times, February 5, 1942, 13.

[5] “Address by Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia at the Opening Conference of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, Hotel Pennsylvania, September 21, 1942,” Spring 3100, October 1942, 4.

[6] “La Guardia Backs Camp Zoning Bill,” New York Times, March 12, 1941, 14.

[7] Allan M. Brandt, No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States Since 1880. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985),166.

[8] “Army, Navy Spur Vice Drive Here,” New York Times, August 11, 1942, 14.

[9] George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World. (New York: BasicBooks, 1994). 336-7.

[10] “Police War Urged on the Pick-Up Girl,” New York Times, July 27, 1944, 19.

[11] Marguerite Marsh, “Prostitutes in New York City, Apprehension, Trial, and Treatment July 1939-June 1940,” (New York City, Research Bureau, Welfare Council of New York City, 1941), 10.

[12] “ARMY, NAVY SPUR VICE DRIVE HERE,” New York Times, August 11, 1942, 14.

[13] Andre Darien, Becoming New York’s Finest: Race , Gender, and the Integration of the NYPD, 1935-1980. (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 55.

[14] Eleonore L. Hutzel, The Policewoman’s Handbook (New York: Columbia University Press, 1933), 20.

[15] Marsh, “Prostitutes in New York City,” 175.

[16] “Mayor Threatens Police on Gambling,” New York Times, September 26, 1942,1.

[17] “La Guardia Orders Policemen to ‘Sock’ Tinhorn Gamblers,” New York Times, September 21, 1942.

[18] “Police Get 20 Days to End Gambling” New York Times, September 27, 1942, 51.

[19] “645 Arrests Made in Gambling Drive” New York Times, September 30,1942, 25.

[20] Dominic J. Capeci, Jr., The Harlem Riots of 1943 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1977), 4.

[21] “Mayor Threatens Police On Gambling” New York Times, September 26, 1942,1.

[22] Domestic Information Section: Research Division, Bureau of Special Services, Office of War Information, Report No. D-3. “The Harlem Race Riot,” August 21,1943, 7. Harlem Riots of 1943 Report Folder, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of the New York Public Library.

[23] “3,000 Attend St. George Breakfast,” Spring 3100, May 1940, 6.

[24] “64,00 Attend Holy Name Breakfast,” Spring 3100, April 1940, 9.

[25] The author was most likely male, since Spring 3100 articles were rarely attributed to female authors.

[26] “State Department of Correction Announces Decrease of 10.1 per cent in Major Crimes During 1941, as Compared with the Year 1940,” Spring 3100, March 1942, 22.

[27] “Address by Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia at the Opening of the War Conference of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, September 21, 1942,” Spring 3100, October 1942, 6.