The Meaning of Evacuation Day Escapes Most New Yorkers Today

By Jerry Mikorenda

If you were a patrician New Yorker during the late eighteenth or the nineteenth centuries, the two most important secular holidays were the Fourth of July and Evacuation Day. The first holiday has held its importance in our cultural psyche; the second is all but forgotten. For those unaware of its significance, November 25, 1783, marked the final withdrawal of British troops from Manhattan after the Revolution.

Unlike, Boston and Philadelphia, New York City has distanced itself from its history. The past is gone preserved more in memoirs and museums than mortar. That makes it even harder to understand the impact that the Revolution’s seven-year occupation had on the city’s culture, terrain, and people. Manhattan with its central location on the East Coast, open deep-water harbor and access to rivers north into Canada made it the strategic prize of the American Colonies.

Torytown Trending

General George Washington knew the British used New York City as its military command center during the French and Indian War. He predicted the British would abandon New England after the Siege of Boston and set their sights on Manhattan to cut the thirteen colonies in two. The military strategy of the day called for burning the city and laying waste to anything that would provide comfort to the enemy. However, the Continental Congress would have none of it. Washington and his raw troops were to defend the city.

Already known as “Torytown,” Manhattan was an amalgamation of merchants, sailors, tradesmen, farmers, financiers and slaves. Also among the hard working were a considerable number of prostitutes whose presence irked Washington to no end. Most of the city’s 25,000 people crammed into the mile-wide area at the southern tip of the island below Chambers Street. Above that (city hall today), an open space called “The Fields” was used by the Sons of Liberty to meet. There an eloquent student from King’s College Alexander Hamilton gave speeches about liberty.

As the uprising morphed into a war for independence during the summer of 1776, Washington personally took command of fortifying Manhattan. He added Forts Washington, Lee and Independence among others to old Fort George first built on “The Battery” during Dutch times. By July, fifty British warships anchored off Staten Island. As word of a pending British attack spread, about a third of the city’s population left. Loyalist refugees and slaves seeking freedom flooded into Manhattan replacing them.

The Battery Included

The Howe brothers were in charge of the offensive – Admiral Lord Richard Howe led the British Navy – General Sir William Howe, its Army. By mid-August, the British had 300 warships and 32,000 troops in the New York region. It was the largest British expeditionary force in history until World War I. On August 22, the Howe’s finally showed their hand methodically shipping troops from Staten Island to Brooklyn where the Americans dug in to meet them at the heights. The Battle of Long Island was America’s first fight since declaring its independence and was the largest clash of the war.

It didn’t go well for the upstarts. Outflanked and outmaneuvered, the Americans ran in retreat. If Howe’s force had pursued and pressed the attack, the war may have ended there. They didn’t. Washington would never again make the mistake of meeting the British head on. He fought a “war of posts” – skirmishes, raids and guerilla warfare. Five battles took place in the environs of New York City as the fall of 1776 approached. The Continental Army lost them all except the Battle of Harlem Heights that allowed Washington and his men to escape into New Jersey.

On September 15, 1776, the British once again raised their flag over Fort George. New York was an occupied city under the thumbscrews of a military commandant. Within six days of the British occupation, a suspicious fire began in The Battery. According to William A. Polf, author of Garrison Town, the blaze started on Whitehall Street with witnesses saying they saw rebels in disguise and shadowy figures setting rooftops ablaze. As the fire swept north up Broadway toward the Hudson River, the steeple on Trinity Church became “a vast pyramid of fire.” Water brigades worked through the night dousing the flames. The conflagration lasted until the next afternoon. When it was over, a quarter of the city’s residences (about 500 homes) were lost.

Mosul on the Hudson

Loyalist hopes that General Howe would install a provisional government run by civilians were quickly dashed. Focused on a military victory, Howe didn’t want his campaign ensnarled in neighborhood squabbles. The local government was powerless as the military reigned supreme. As the embers of the fire still smoldered, more than one hundred suspects were arrested. Among them was a twenty-one year old Connecticut spy making his way back to the American camp. Hanged the next morning, Nathan Hale’s legend grew in death. He became the country’s first rock star.

Manhattan became Mosul. With winter approaching, tents popped up along the western Battery where homes once stood. They called it “Canvas Town.” For those who could afford housing rents kept escalating. If British troops desired a home, the occupants were forced out. Agriculture in the city shut down too. Where local produce was once plentiful, food had to be imported. The price of flour soared and the black market thrived. New York Harbor played host to privateers stealing cargo from American and French ships. Spies were everywhere. Neighbors watched each other reporting any suspected improprieties to the authorities.

Martial law took its toll on the populace too. Rape, robbery, and murder were common crimes against civilians by the occupying forces. British soldiers mugged New Yorkers in broad daylight. Polf cites the case of a miller who tried to collect for services rendered and was horsewhipped then murdered. In another incident, troops invaded the home of a merchant robbing and killing him. For the most part, British officers ignored the atrocities inflicted upon the locals. Their abusive behavior turned Tories into Patriots as one English official noted, “Britain’s armies made more rebels than they found.”

Harbor Horrors

In mid-November 1776, English forces took Fort Washington the last rebel stronghold. The battles to secure the island for British hands resulted in the capture of nearly five thousand American prisoners. With Manhattan finally cleared of Washington’s troops, the city was coming to grips with its role in the war – an immense prison. To the British mindset, New York’s sugarhouses used to store barrels of sugar and molasses were ideal for housing prisoners. The Livingston, Rhinelander and Van Cortlandt sugarhouses in lower Manhattan were each at least five stories high. The British managed to herd hundreds of men into each of these buildings. The prisoners didn’t survive long. Each day a “dead cart” collected ten or more bodies from each location and tossed them in ditches.

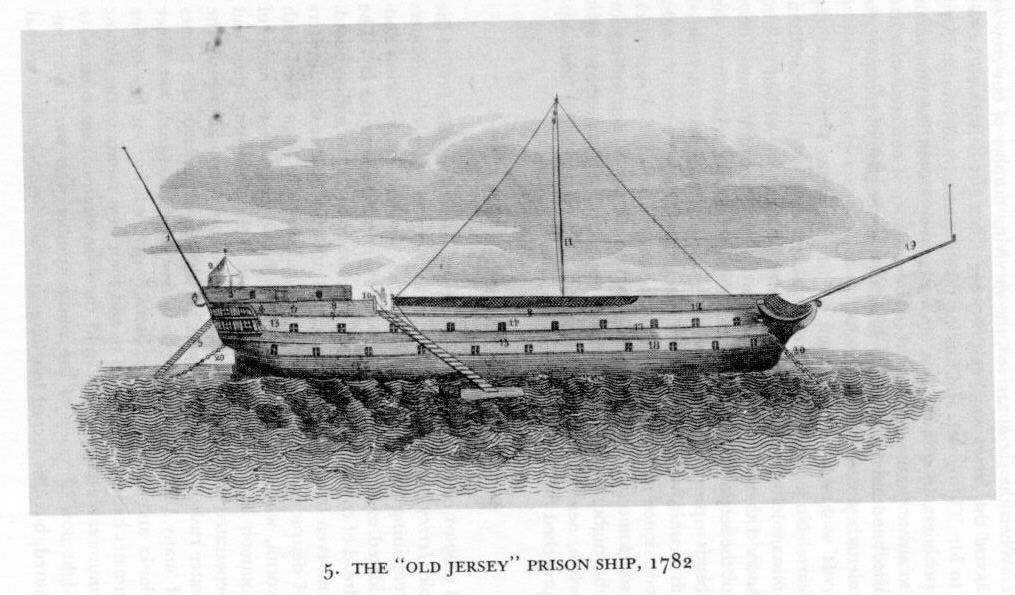

Even these measures weren’t enough to house all the prisoners taken. Ships no longer seaworthy were stripped of their masts and converted into prison barges. At any given time, ten or more such barges were afloat in the Hudson, East River and Wallabout Bay. Conditions in these prisons were beyond horrific.

According to Dr. Edwin Burrows author of Forgotten Patriots, some 30,000 Americans were confined in New York during the Revolution with a mortality rate between sixty and seventy percent. Burrows’ research shows that “more Americans lost their lives in the prisons of New York, and the prison ships of Brooklyn, than anywhere else – between two and three times as many as those who died in combat.”

In Burrow’s book, the words of a Patriot soldier from Connecticut, Robert Sheffield, recalled the terror of living under those conditions:

“Their sickly countenances and ghastly looks were truly horrible; some swearing and blaspheming; some crying, praying and wringing their hands, stalking about like ghosts and apparitions; others delirious and void of reason, raving and storming; some groaning and dying, all panting for breath; some dead and corrupting. The air was so foul at times, that a lamp could not be kept burning, by reason of which three boys were not missed until they had been dead three days.”

For years afterward, the bones of these prisoners washed up on the city’s shores.

Back in NY Groove

In the end, logistics led to liberty. The British were ill-equipped to wage a drawn-out campaign such a great distance from home. The surrender of General Cornwallis at Yorktown in November 1781 set in motion a two-year peace process that would put New York City back on the map and expose the flaws and pitfalls of a startup nation.

Manhattan became the epicenter of a mass withdrawal of all things British. Loyalists had to give up their property with death sentences issued on some. Everyone drawn to the city during the occupation was now escaping the new republic through it. The question of reparations hung over the city. Who owned what after seven years of foreign military rule was just one of the questions New Yorkers wrestled with.

When Washington met British Commander Sir Guy Carleton in April 1783 foremost on his mind was reacquiring “all Negros and other property.” Carleton stated the British wouldn’t renege on their promise of freedom to all slaves who joined their cause, “delivering up Negros to their former masters… would be a dishonourable violation of the public faith.” Congress begrudging conceded that it was in no position to demand the return of slaves as refugees and foreign troops continued to depart Manhattan. The Black Pioneers were among the last regiments to leave Manhattan Island.

Evacuation Day

For days, Washington and his men waited on the outskirts of the city for the last vestiges of the British force to leave. At 1 PM on November 25, 1783, cannon fire signaled the British were gone, but the end didn’t come without hijinks. A woman chided by a British officer for having raised an American flag as he rode by had his nose bloodied with a crack from her broomstick.

In turn, the British greased the flagpole at Fort George making it almost impossible for the young republic to show its colors as the enemy departed. Embarrassingly, the Union Jack would have flown over the city as Washington’s troops reached The Battery if not for a quick thinking sergeant. The resourceful John Van Arsdale hammered cleats into the pole climbing to the top to hoist the American flag. Thus, his decedents raised the flag every year at Evacuation Day ceremonies through the Nineteenth Century.

The city was in as poor a shape as the soldiers parading down its streets. Many watching the Continental Army march past them wept seeing the conditions these combatants endured. As the haggard militia troops wound down Broadway, they couldn’t have possibly imagined the grandeur and spectacle that Manhattan would become. Boston, Philadelphia, and other towns also marked the British exiting their cities (on different dates). By the 1790s, Evacuation Day was a “national” holiday in New York City.

Opulent Obsolescence

Evacuation Day’s stature grew during the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1864, Confederate saboteurs chose November 25 to launch a series of terrorist attacks throughout the city. Confederates planned to burn Manhattan to the ground through a series of coordinated attacks using “Greek Fire.” Barnum’s Museum, the Astor House, and the Winter Garden Theater (where all three Booth Brothers performed that night) were among the dozen or so targets. Poor weather and providence helped avoid disaster.

Evacuation Day peaked as a festival on its one-hundredth anniversary in 1883. A parade featuring 25,000 troops and 300 warships was presided over by President Chester A. Arthur. The celebration lasted through the night topped off with banquets that would have embarrassed Washington and his men with their opulence. The intervening years showed a declining interest in Evacuation Day activities. The newly proclaimed Thanksgiving holiday was more in keeping with modern times. Allied with the British in World War I, 1916 marked the last official celebration of the evacuation in New York City.

Toast for Today

Now, two hundred and forty years after the British occupation began, there is a movement to revive the holiday. Earlier this year, the area around the Bowling Green flagpoles was renamed “Evacuation Day Plaza.” November 25, 2016 will renew the annual parade and ceremonial flag raising (minus the pole climbing) by the Veterans of the Corps Artillery. Perhaps going forward the celebrations could also include a more reflective moment as well.

After the Continental Army’s triumphant march into the city, Washington and his officers dined at Fraunces Tavern on Pearl Street. During the course of the evening, there were thirteen toasts. Some were heartfelt, some mournful, others prophetic. The next to last toast of the evening seemed as much a reminder as it was a promise to future generations.

“May America be an Asylum for the persecuted of the Earth”

Maybe Evacuation Day should serve as a way to remember when this crowded little Island was part of a third world country with refugees living in tents trying to escape a barbaric foe. A time when the bold idea of a new nation of united commoners sought legitimacy for all people in a world beset with kings. Hoisting a hot ale flip to such noble sentiments would make for a worthy day indeed.

Jerry Mikorenda is a freelance writer. His articles have appeared in the New York Times, Newsday, and the Boston Herald, and in various magazines and blogs.