Taking Care of Brooklyn: An Interview with Erin Wuebker

Interviewed by Katie Uva

Today on the blog, editor Katie Uva talks to Erin Wuebker, Assistant Curator of the Brooklyn Historical Society's new exhibition, Taking Care of Brooklyn: Stories of Sickness and Health. The longterm exhibition, on view until June 2022, examines 400 years of Brooklyn's history through the lens of public health.

Taking Care of Brooklyn exhibition, 2019.

Can you start us off with a bit of an overview of the exhibition?

For 400 years, Brooklyn has served as a crucible for the social forces that determine public health — war, housing, urban crowding, poverty, working conditions, racism and sexism, and more. Brooklyn has been a site of bloodshed and genocide, a densely populated urban center, an immigrant enclave, an industrial powerhouse. It has fostered unprecedented innovation and unprecedented inequality. Against this backdrop, generations of Brooklynites have contended with epidemics of infectious disease, struggled with chronic conditions, experienced childbirth and death, and fought for access to healthy food and uncontaminated water.

Brooklynites — parents and friends, nurses and physicians, activists and reformers, and many others — have also tended the borough’s sick. Residents have long debated who is qualified to give care, who deserves care, and how care should be provided. They have established businesses, institutions, and practices that have transformed people’s experiences of care. And in the face of government or medical neglect, they have organized, protested, and devised alternate forms of care. In this exhibition, we unfold the stories of the people of the past who have taken care of Brooklyn.

How did you decide on the exhibition themes?

Our exhibition themes — care, conditions, inequality, and resistance — really emerged from our primary research. For example, we found stories of so many caregivers in Brooklyn’s past — nurses, physicians, parents, midwives — that we knew this would be prominent in the exhibition. But we also wanted to challenge visitors’ understandings of some of these themes. Activism or art can be a form of care, chicken soup or a visit from a neighbor can be care.

These themes also made sense with our social history approach. Health is not just about doctors and diseases, but also the many social factors that shape the health of individuals and communities, such as discrimination, poverty, housing, education, and much more. Our research showed how social conditions have resulted not only in health inequities, but also many activists that have worked to challenge those inequities and promote health for Brooklynites.

What are some ways Brooklyn fueled innovation and progress in medicine?

Brooklyn has long been a center of industry, and has attracted important innovators and businesses. Some multinational pharmaceutical companies got their start here, such as Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer. In the 1860s, Edward R. Squibb developed the first commercial-grade form of ether at his Brooklyn factory, choosing not to patent the process and encouraging others to use it. This anesthesia innovation eased the excruciating and terrifying experience of surgery for hundreds of thousands of Civil War soldiers. Pfizer also has its origins in 19th century Brooklyn. While it was also one of the earliest companies mass producing pharmaceuticals, it played a particularly important role during WWII. It was the first company to mass produce penicillin, which was urgently needed for the war effort.

Charles Pfizer & Co. Inc., Penicillin bottle, 1944, M1990.13; Brooklyn Historical Society.

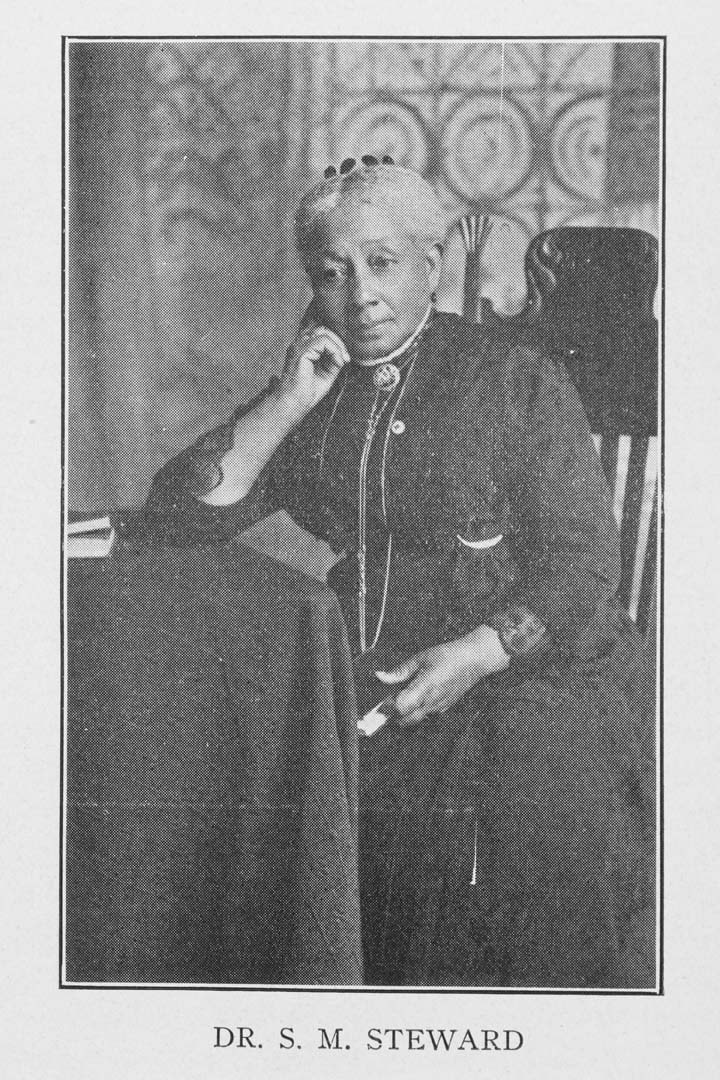

Brooklyn medical institutions have also helped push innovation in medicine. Long Island Hospital, for example, was one of the first schools in the nation to use bedside teaching practices and to use cadaver dissection in an anatomy curriculum. The hospital also developed the first bacteriological laboratory in 1888. Many Brooklynites who would go on to play important roles in medicine were also educated at LICH, such as Susan Smith McKinney Steward and Alexander Skene.

How did consolidation in 1898 affect the public health landscape in Brooklyn?

Long before consolidation, Brooklyn and Manhattan residents understood that their health was linked. During 19th-century outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever, Brooklynites debated shutting down daily ferry service to Manhattan to prevent the spread of disease. However, the close business ties between the two cities made this impossible. By 1866, a Metropolitan Board of Health was established that served both Manhattan and Brooklyn. However, Brooklyn still had their own separate Board of Health and had a fairly robust public health infrastructure before consolidation, such as sewers, public health laws, and numerous hospitals, schools, and dispensaries. Consolidation itself did not come up in our research as such a big turning point in terms of public health, however.

What are some major conflicts over healthcare in Brooklyn's past?

Two major conflicts that emerged in our research were debates over the role of government in public health and fights for health equity. As public health developed, government became more involved in the everyday lives of Brooklynites. But, sometimes residents pushed back against this. One stark example was the fierce debates over smallpox vaccination in the 1890s. In the midst of an outbreak, Brooklyn’s Board of Health fervently tracked down cases, inspected and sanitized people’s homes, quarantined and vaccinated people. The law also changed during this epidemic, requiring all school children to be vaccinated for smallpox. A small but vocal group of Brooklynites started organizing an anti-vaccination movement in the city, which gained steam across the nation as other cities grappled with the issue of balancing individual liberties with protecting the health of the public. The exhibition highlights a number of challenges from Brooklynites during this smallpox outbreak. As we saw with the recent measles epidemic, we’re still grappling with some of these political issues wrapped up in public health even today.

Another major conflict has been fighting for equity in healthcare. There are many stories of Brooklynites fighting for equitable access to hospitals, good housing, medical education, and just money and attention from people in power. In particular, there is a long history of Black activists in Brooklyn challenging racism within the borough’s institutions, while also providing care to Black communities when no one else would. This is a through line in a number of different stories in the exhibition, from early physicians challenging the color line in schools and hospitals, to Brooklyn’s only Black settlement house fighting tuberculosis, to grassroots lead poisoning campaigns in the 1960s and 1970s. In consulting with public health professionals working today and looked at contemporary community groups, this also emerged as an issue that many Brooklynites are still fighting for.

Susan Smith McKinney Steward, 1921, from T.G. Steward, Fifty Years in the Gospel Ministry; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutsom Research and Reference Division, the New York Public Library.

Do you have an artifact or feature in the gallery you'd like to highlight here?

Some of my favorite artifacts from our collections are comic and coloring books about HIV/AIDS from the 1990s. They were created by Brooklynites working to educate people about HIV/AIDS and challenging a lot of misinformation and stereotypes that were out there about the illness. They are a real window into what a challenge it was in that first decade of the disease to get accurate information to people and how that led to shame, fear, and discrimination. They are also creative and funny and lovely to look at.

Coloring book, comic book, newsletter, posters, and art piece related to HIV/AIDS in Brooklyn, all 1980-1990s; Taking Care of Brooklyn exhibition, 2019; Brooklyn Historical Society.

What are major health issues in present-day Brooklyn, and how does the exhibition engage with them?

Health equity is one of the most important issues facing Brooklynites today. We highlight grassroots organizations working to challenge health inequities today, such as Ancient Song Doula Services that provides doulas for to underserved women in an effort to combat higher rates of infant and maternal mortality among Black women in particular. More broadly, the exhibition also traces the historical roots that have led to health inequities and the work of earlier activists trying to challenge these conditions. Related to birth equity, Bed-Stuy residents in the 1950s pushed for a hospital to be built in the newly primarily Black and very dense neighborhood, citing higher rates of infant mortality, tuberculosis, and other health issues. This is just one of many stories of activists challenging inequities in health care in Brooklyn’s past that are still issues for residents today.

Infant Mortality Rates, 1929–1931, Atlas of the Slum Clearance Committee of New York, 1933–1934, NYC-1933-1934.A; Brooklyn Historical Society.

How does looking at Brooklyn through a healthcare and medicine lens challenge assumptions about this borough's history, or tell us something new?

Much of the history that is out there about New York, especially the history of public health and medicine, focuses on Manhattan. In starting the research for this exhibition, we found very little scholarship on the topic, so we really had to go straight to the primary sources. But to understand the city as it is today, we have to look at all of the boroughs even if they were separate cities at one point, like Brooklyn was.

Taking Care of Brooklyn exhibition, 2019; Brooklyn Historical Society.

Erin Wuebker is the Assistant Curator of Taking Care of Brooklyn. She also teaches American history and women and gender studies at Queens College.