The History of Mexican Food in New York

By Lori A. Flores

Though post-COVID statistics will reflect restaurant closures, downsizing, or “ghost kitchens,” as of the summer of 2020 there were 27,556 restaurants operating in New York City, 977 of which were Mexican. To some, this latter number might not be surprising (and even seem low given the popularity of Mexican cuisine). Yet just a few decades ago, New York was a place where Mexican food was hard to find. It lagged behind other cities like Chicago, San Antonio, or Los Angeles that claimed larger Mexican-origin populations and a longer history of Mexican restaurants.

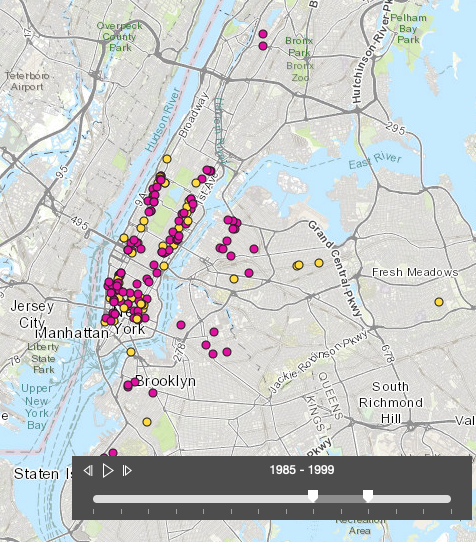

The Mexican Restaurants of NYC StoryMap website allows users to use a time-slider to view the proliferation of Mexican restaurants over time.

The Mexican Restaurants of New York City project, created by a group of Latinx historians at Stony Brook University (SUNY), is a website that narrates and maps the history of Mexican food in the Big Apple from 1930 to the present day. Using data collected from historical archives, city records, English and Spanish-language newspapers and magazines, Google, Yelp, and food blogs, the website contains “StoryMaps” that show viewers four different things: the proliferation of Mexican food businesses in the five boroughs over time; where Mexican restaurants are located compared to where Mexican New Yorkers actually live; the history of how Mexican food has been priced in the city; and the prevalence of Mexican food trucks/carts. The website’s historical database of over 350 restaurants (and still growing) provides a sketch of how culinary change happened in New York City’s Mexican foodscape.

Though it took time for Mexican food to spread in New York, the city had been a longtime home for Latinx communities. Spaniards had settled centuries prior and were followed by Cuban and Puerto Rican political exiles of the 1800s and early 1900s. Mexicans migrated to New York in the early 20th century, arriving either by ship from Mexico or by train after work stints in the cotton fields of Texas, stockyards and factories of Chicago, or auto assembly lines of Detroit. Though some public spaces served Latin American food by the late 1930s — Cuban dining rooms existed near cigar factories in lower Manhattan, and migrant entrepreneur Juvencio Maldonado owned a Mexican restaurant in Times Square — they were few and far between. In 1959 Spaniards Louis Castro and Manuel Vidal opened El Charro in Greenwich Village, and Mexican restaurateur Carlos Jacott debuted El Parador in Midtown East. Mexican Village, a restaurant owned by a Mexican woman, served the NYU area beginning in the mid-1960s, and two Irish businessmen opened the Tex-Mex establishment El Coyote near Astor Place in 1981.[1]

The facade of Zarela, a regional Mexican restaurant that opened in Midtown East in 1987. Photograph from the Zarela Martinez Papers, Schlesinger Library, Harvard University.

It was during the 1980s that New York City’s appetite for Mexican food noticeably increased. At the beginning of April 1981, the New York Daily News published an article entitled “Tex-Mex Fever Hits Manhattan.” Relying heavily on flour tortillas, meat, red chile, cumin, pinto beans, and melted cheese, Tex-Mex cuisine was New York’s latest obsession. More people were traveling to Mexico as tourists and becoming curious about ethnic cuisines in general, and a sizable population of Southwesterners were transplanting in the Northeast and creating (or demanding) Mexican food that reminded them of California, New Mexico, or Texas. Fort Worth natives June Jenkins and Barbara Clifford owned popular Tex-Mex restaurants Juanita’s and The Yellow Rose Café respectively, and eateries with names like Santa Fe, Pancho Villa’s, Margaritas, and Tortilla Flats dotted Manhattan. A few restaurants offering upscale and regional Mexican cuisine, such as Rosa Mexicano and Cinco de Mayo (owned by Cuban-born and Spanish-raised designer and chef Josefina Howard) and Zarela (owned by Mexican immigrant caterer and chef Zarela Martinez) opened to great fanfare in the late 1980s and began to educate diners on what distinguished Jaliscan cuisine from Oaxacan from Veracruzan.

Access to certain Mexican food items or ingredients, however, was still a bit challenging at this point. Some restaurateurs invested in shipping in their tortillas or chiles from the Southwest because suppliers in Manhattan were scarce. Two tortilla factories — opened by migrant cousins from Puebla, Mexico — did exist but they were located further away in New Jersey and Brooklyn. New York food critics frequently lamented in newspapers and magazines that the Mexican food scene remained stunted because “relatively few Mexicans have chosen to make their home here.”[2]

The next decade changed everything, both in terms of ingredient procurement and demographics. Along with Central Americans fleeing civil wars, an influx of Mexican migrants came to the United States during the late 1980s and 1990s due to a series of events. The Mexico peso had suffered devaluation; a 1985 earthquake devastated the states of Michoacán and Guerrero; the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) legalized certain categories of undocumented immigrants; and the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) sunk the price of Mexican corn so low that the agricultural working class felt compelled to migrate north for work. Whereas the US Census counted 23,761 Mexican New Yorkers in 1980, there were 61,722 by 1990, making Mexicans the fastest-growing Latinx population across all five boroughs.[3] Specifically, migrants from the state of Puebla moved to New York City in droves, motivated by word-of-mouth and chain migration networks. The city’s new nickname “Puebla York” signaled the noticeable presence of these Pueblan residents.

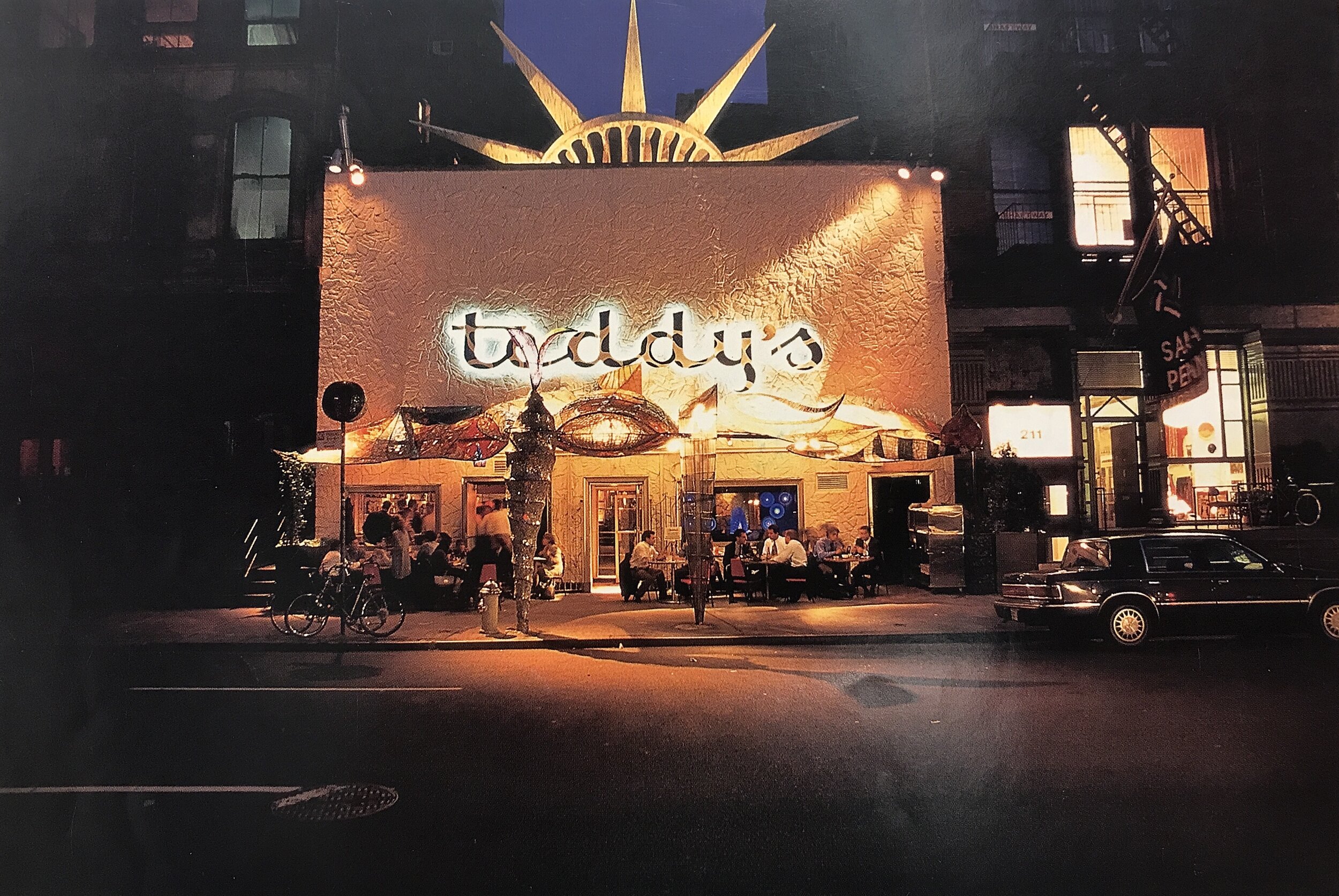

El Teddy's, a Mexican restaurant in Tribeca, in 1997. Photograph from the New York Public Library Picture Collection.

Many of these Latin American newcomers took jobs in factories, construction, domestic service, and restaurants but experienced exploitation by employers who paid low wages and counted on workers’ economic desperation or fear of deportation. Some migrants decided to establish their own food businesses. They opened taco trucks and tamale pushcarts in Brooklyn and Queens, panaderías and bodegas in East Harlem and the Bronx, and modest hole-in-the-wall restaurants in Manhattan. A tortilla “boom” also occurred between 1990 and 1993 as more than twenty new tortilla factories opened. Bushwick, Brooklyn became the “Tortilla Triangle” with its three major tortillerías (Buena Vista, Chinantla, and Piaxtla), all named after towns in Puebla.[4] With their pushcarts and big steaming aluminum pots, Mexican street vendors enticed passersby with one-or-two-dollar tacos, elote, and tamales. Gradually, all of these different food entrepreneurs turned neighborhoods that had previously been Italian, Greek, Chinese, or Puerto Rican into “Mexican” ones as well. The 1990s also marked a peak in the nation’s fascination with Mexican food. Salsa surpassed ketchup as the best-selling condiment in the country in 1991; the number of Mexican restaurants rose fifty-eight percent from 13,034 in 1985 to approximately 20,600 in 1994; and Taco Bell, McDonald’s, and Chipotle won over the public with soft tacos and customizable burritos.[5]

By the autumn of 2006 the New York Daily News was proudly proclaiming, “New York is finally a city with great Mexican food.”[6] Residents could easily find tamales, cemita sandwiches, and Mexican candies in Bronx bodegas or street carts in Queens. On the weekends, Latinx and non-Latinx populations alike swarmed the taco stalls along the soccer fields of Riverside Park in Manhattan and Red Hook, Brooklyn. And by 2010, the city census counted 377,000 Mexicanos among the 2.5 million total Latinx people who made up Nueva York.

The proliferation of Mexican food both slow and fast, haute and humble, that we have hitherto enjoyed in New York and the wider United States is due to citizens and migrants of varying class statuses who have created an incredible diversity of Mexican cuisine. Yet this culinary contribution historically and currently intersects with a disturbing discourse about “authentic” Mexican food being inherently inexpensive. As historian Jeffrey Pilcher has argued, “Very few Mexican restaurants can command prices comparable to those of French restaurants, even when using the same fresh ingredients and, in many cases, the same Mexican workers. Customers have simply refused to consider the two cuisines as equals.”[7] The long colonial and exploitative relationship that the United States enjoyed with Mexican land and labor since the 1800s, and US citizen tourism in Mexico that gained momentum from the mid-20th century onward, certainly shaped perceptions of Mexico as an exotic vacationland where sex, alcohol, and spicy food could be consumed cheaply.[8] Arguably, the late-20th century devaluation of Mexican food that occurred in New York and across the nation happened in tandem with increasing Mexican immigration to the United States. As smaller immigrant-owned food enterprises like taco trucks, street carts, and taquerías became more prevalent, this solidified consumers’ ideas that Mexican food should be naturally low-priced. In discussing Chinese cuisine’s historical valuation, scholar Krishnendu Ray observed that The New York Times gave tremendous attention to Chinese restaurants in 1965 but dropped coverage considerably once that year’s Hart-Cellar Immigration Act resulted in an influx of Chinese immigration to the United States. He suggested “an inverse relationship between the prestige of a cuisine… and the number of immigrants.”[9] As New Yorkers saw more Mexican immigrants moving throughout the city and taking on a variety of low-wage jobs, the notion that immigrant newcomers would be grateful for any money they made in the United States (because it was inevitably more than they could earn back home) made it more challenging for everyone along the Mexican food-providing chain to persuade diners that their ingredients and labor deserved a certain level of money and respect.

Users of the map can click on areas to view the number of Mexican food trucks recorded as operating in their neighborhood.

This devaluation of Mexican food still continues today. “I’m not going to pay that amount for guacamole, chips, and salsa — they should be free”, “Mexican food shouldn’t cost this much”, or “It’s cheap; that’s how you know it’s authentic” — remain common refrains. This false equivalency of “authenticity” with cheapness can then fuse onto Mexican food laborers as well. Particularly if they are migrants and/or undocumented, Mexican-origin workers in the US food industry (at all links in the chain, from farms to processing factories to warehouses to restaurants) are still not paid enough for their labor, despite their role in maintaining and shaping our nation’s food systems. The COVID-19 pandemic only illuminated this reality more brightly. Social media has also fueled the rhetoric of “authenticity” and strengthened stereotypes about what cuisines’ price points should be. Much like Chinese food, Mexican food has been unable to escape the notion that it should be inexpensive to be authentic. On the review site Yelp, where disproportionately young and white users “are constantly assessing the alleged verisimilitude of a restaurant’s food, atmosphere, and even the ethnicity of its employees,” customers look for nonwhite patrons, humble or nonexistent decor, and low prices to affirm the “realness” of a Mexican restaurant.[10] One textual analysis of 2016-17 Yelp reviews for the top twenty Mexican restaurants in New York City concluded that commenters used low prices, dirty floors, plastic chairs, and nonwhite customers to vouch for the establishment.[11] A few restaurants, if appropriately branded as haute/exotic or known for a particular chef, will be able to charge higher prices. Yet the reality remains that many Latinx restaurateurs and food entrepreneurs encounter pushback or judgment when they place a higher value on their food and labor. Meanwhile, elevated Latinx cuisine can exist unquestioned in the hands of white chefs who almost never have to qualify their decision to charge certain prices. The StoryMap site, through labeling the price points of various establishments and the identities of their owners when they can be found, gives users a visual sense of what kind of Mexican food businesses are priced higher and lower, and where.

The Mexican Restaurants of NYC Project is a digital love letter to Mexican food in New York that is still evolving; its creators want to continue crowdsourcing community information about missing restaurants, opening and closing dates, owners’ names, and copies of menus. The array of Mexican food and foodmakers in New York is not a feature of the city to be taken for granted or considered inevitable, but recognized as a long historical process of migration, entrepreneurship, exploitation, and innovation all bound up together.

Lori A. Flores is an Associate Professor of History at Stony Brook University (SUNY). She is the author of the award-winning book Grounds for Dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican Immigrants, and the California Farmworker Movement (2016), the co-editor of The Academic's Handbook (2020), and is currently researching and writing a new book on the history of Latino/x food workers in the US Northeast from 1940 to the present day.

[1] Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof, Racial Migrations: New York City and the Revolutionary Politics of the Spanish Caribbean (Princeton University Press, 2019); Jeffrey M. Pilcher, “‘Old Stock’ Tamales and Migrant Tacos,” Social Research, Vol. 81, No. 2 (Summer 2014), 453; Suzanne Hamlin, “Tex-Mex Fever Hits Manhattan,” NY Daily News, 2 April 1981, 2-3.

[2] Eric Asimov, “$25 and Under,” New York Times, 29 May 1992, C20; Seth Kugel, “How Brooklyn Became New York’s Tortilla Basket,” The New York Times, February 25, 2001, www.nytimes.com/2001/02/25/nyregion/new-yorkers-co-how-brooklyn-became-new-york-s-tortilla-basket.html.

[3] Gael Greene, “The Whole Enchilada,” New York Magazine, 23 January 1995, 38.

[4] Kugel, “New York’s Tortilla Basket.”

[5] Donna Gabaccia, We Are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans (Harvard University Press, 1998), 219; Greene, “The Whole Enchilada.”

[6] Rachel Wharton, “Mexican Revolution: A favorite city cuisine just keeps getting more authentic,” NY Daily News, 15 September 2006, 71-72. Folder 10, Box 3, ZMP.

[7] Pilcher, Planet Taco, 201.

[8] By 1953 Mexico was the most common travel locale for US tourists. Cecilia Márquez, “Becoming Pedro: ‘Playing Mexican’ at South of the Border,” Latino Studies Vol. 16 No. 4 (Dec 2018), 480.

[9] Krishnendu Ray, “Ethnic Succession and the New American Restaurant Cuisine” in David Beriss and David Sutton, eds., The Restaurants Book: Ethnographies of Where We Eat (Berg, 2007), 104-105.

[10] Dylan Gottlieb, “‘Dirty, Authentic…Delicious’: Yelp, Mexican Restaurants, and the Appetites of Philadelphia’s New Middle Class,” Gastronomica Vol. 15 No. 2 (Summer 2015), 39-41.

[11] Sara Kay, “Yelp Reviewers’ Authenticity Fetish Is White Supremacy in Action,” Eater NY, January 18, 2019, https://ny.eater.com/2019/1/18/18183973/authenticity-yelp-reviews-white-supremacy-trap.