The Struggle for Teacher Education in 19th Century New York

By Sandra Roff

Teaching as a profession aims to achieve the most noble of principles — educating children to be responsible, productive citizens. Unfortunately, the teachers hired in the early years of the new republic and well into the nineteenth century were usually untrained and unprepared for the job ahead. The civic-minded movers and shakers in New York City at the time were interested in the education of its youth, but the path to securing qualified teachers for the schools was slow to be realized.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "Bridewell, and Charity-School, Broadway, opposite Chamber Street - February 1808."

In early New York City there were two choices for primary school education — charity schools or “pay schools.” Pay schools were for those who could afford tuition and charity schools offered a limited education for poor New York City children.[1] In 1832 this changed when “public notice [was] given that schools were now open to all as a common right, and that every effort would be made to render them attractive and desirable to all classes of citizens.”[2]

Now that more New York City children were entitled to an education, the city would need to employ more teachers. How were these new teachers being prepared for the responsibility of teaching the city’s children? Since higher education was limited for all students in the early 19th century, it was academies, seminaries and high schools that trained aspiring teachers.[3] High schools were open to both men and women in New York City by 1826, an extremely controversial move.[4] The argument against women moving out of the domestic sphere was challenged on moral, religious and ethical grounds, but reason did win out and it was hoped that women would prove their worth as competent teachers. In the 18th and early 19th century teaching was male dominated, and women were only expected to do informal teaching in the home. However the population in New York City was growing and the schools needed qualified teachers. Male teachers were difficult to find and because women were available and willing to take on the challenge, the primarily male teaching force shifted to a predominately female one by the end of the 19th century.[5]

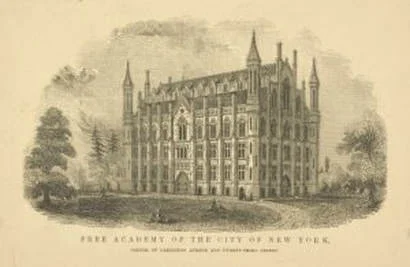

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "Free Academy of the City of New York, corner of Lexington Avenue and Twenty-Third Street. Exterior view"

In New York City the opportunities for a college education were limited and available to white, middle and upper class young men who could afford the tuition at either Columbia University or the University of the City of New York (later New York University). No municipality had assumed the cost of funding higher education for its residents and this became a fierce political battle in New York. However, free publicly supported higher education did finally become a reality, and New York City became the first municipality in the United States to open a free, publicly supported institution of higher education for young men in 1849 — the Free Academy.[6]

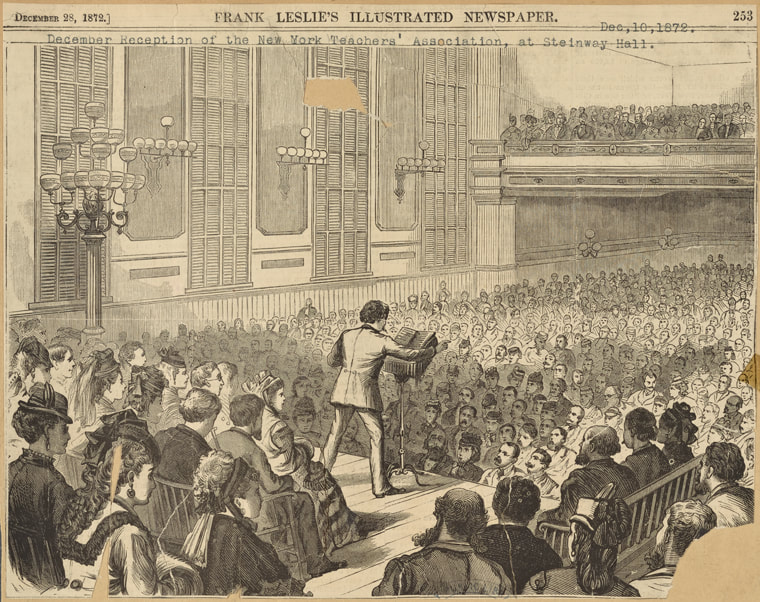

Now that men had an opportunity to obtain an advanced education in New York City, wasn’t a similar institution for women the next logical step? According to the 19th century “cult of domesticity” women were supposed to be satisfied practicing piety, purity, submission and domesticity within the confines of the home and education was only to reinforce domestic ideals and not to improve the intellect.[7] Support for this doctrine came from middle and upper class women who did not need work to support themselves, but the women who would benefit most from a higher education were from a lower socioeconomic class who needed to work, and a course to prepare them for teaching would serve them well. Support for women to enter the field of teaching appeared in the writings of Catherine Esther Beecher, an early crusader for women, who swayed many a skeptic.[8] Henry Barnard was another proponent, and he introduced the idea of teacher institutes which spread quickly to Connecticut, New York and around the country.[9] In 1845 “The Teacher’s Institute of the City and County of New-York” was formed, but not surprisingly in the constitution of the Institute there is specific mention of the inclusion of male teachers, but no reference is made to female teachers![10] By 1848 the Teacher’s Institute was replaced by the “Teacher’s Association of the City and County of New York,” the purpose of which was for “mutual improvement in the art of teaching…”[11]

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "December reception of the New York Teacher' Association at Steinway Hall"

In New York City concern for training teachers can be traced back further than the Teachers’ Institute of the 1840s. The Normal School model for educating teachers had European origins, and the first normal school in America is thought to be The Teacher’s Seminary in Concord, Vermont in 1823.[12] Normal School education for New Yorkers began in 1834 when three Saturday Normal Schools were opened — one for white females, one for white males, and a third for colored females. The curriculum covered by these Saturday Schools was extremely limited, and was “little more than Grammar, Geography, Arithmetic, and Astronomy. Instruction is likewise given to the females of this department in Algebra, Geometry, and Trigonometry.”[13] The lack of attention to teaching skills was emphasized when Assistant Superintendent of Education, Henry Kiddle, commented in 1857, “Placed in the school-room with very little but the knowledge of what is to be done, the how to do it is, as it were, a distant haven on the other side of a pathless ocean which is to reach without pilot, compass or chart…”[14] Teaching instruction was limited to those already employed in the primary schools, but the inequality of these Normal Schools was problematic when the Board of Education in 1853 wanted to make it obligatory “on every teacher below the grade of Principal to attend regularly upon the Normal School, under penalty of losing his position, unless excused by this committee.”[15] The issue was that for men the Normal School was opened from 5-7 five days a week, but for women it was only open on Saturdays from 9-2. Any women with other responsibilities who could not attend classes would lose her job.[16]

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection, The New York Public Library. "Public schools. Hall of the Board of Education, Elm St."

The future of female teachers in New York City was of concern to the populace and as early as 1854 a school for women similar to the Free Academy for men was proposed by the Board of Education. The debate on the feasibility of a female institution of higher education for women went on for several years with arguments such as: “All the considerations which impel us to desire a high standard of excellence for our sons, should lead us to desire the same standard of excellence for our daughters.”[17] Politics always played a part in the decisions that the Board of Education made. Using taxpayers money for women’s education was not a popular cause and this can be surmised by looking at the annual reports of the Board of Education. It was not until 1868 that real progress was made and the Board of Education once again took up the issue, and went so far as stating that a site for a school was already selected.[18]The final step came on November 13, 1869 when the Committee on Normal, Evening and Colored Schools submitted a report and adopted the resolution establishing a daily Female Normal and High School.[19]

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "Normal College of the City of New York"

The long road to free, municipal supported higher education for women was finally a reality. Women of New York City could now obtain the best teacher training available at the time. In an 1892 Harper’s Bazaar article the college was described as opening as a three year institution, but by 1880 it was extended to a fourth year. “The curriculum has from the first included English, history, grammar and composition; Latin, modern languages, mathematics; physical, natural, and mental sciences; besides pedagogy, or the art of teaching; but of later years still higher branches have been added.”[20] The school remained for years an oddity and seemed to only gain recognition when the annual commencement took place. The Normal College became Hunter College in 1914 and legions of New York City teachers received their degrees there. New York City and the city schools underwent many changes in the years following the establishment of the original Normal College. Immigration reached new heights and New York City became home to all races, religions and ethnic groups, who looked to education as the route to Americanization. Now with municipal colleges for both sexes in New York City, teachers could receive the proper training for a career in education. The benefit for the city’s children has been enormous, helping to fulfill the belief of our founding fathers in the importance of educating the citizenry for a democratic society.

Sandra Roff is Professor and Head of Archives & Special Collections at Baruch College, City University of New York.

Notes

[1] Carl F. Kaestle, The Evolution of An Urban School System: New York City, 1750-1850 (Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1973), 91.

[2] Thomas Boese, Public Education in the City of New York: Its History, Condition, and Statistics (New York: Harper & Brothers, publishers, 1869), 59.

[3] Margaret A. Nash, Women’s Education in the United States, 1780-1840 (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2005): 60, 66.

[4] James W. Fraser, Preparing America’s Teachers: A History.(New York: Teachers College, 2007):82. “Address Delivered on the Opening of the New-York High School for Females,” American Journal of Education 1, no. 5 (1826): 270.

[5] Nash, Women’s Education, 59-60.

[6] Sandra Roff, “Spreading the News: Revisiting the History of the New York Free Academy Using 21st Century Technology,” American Educational History Journal 34, nos. 1 & 2 (2007): 148.

[7] Barbara Welter, “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860,” American Quarterly 18, no. 2, P.t 1 (1966): 152, 154, 162.

[8] Jo Ann Preston, “Domestic Ideology, School Reformers, and Female Teachers: Schoolteaching Becomes Women’s Work in Nineteenth-Century New England,” The New England Quarterly 66, no.4 (1993): 532.

[9] Christine A. Ogren, The American State Normal School: “An Instrument of Great Good" (New York: Palgrave Macmillian, 2005): 20.

[10] Joseph McKeen, “The Teacher’s Institute of the City and County of New-York: Constitution,” The District School Journal of the State of New York6, no.2 (1845): 28.

[11] New York Society of Teachers, The Mathematical Club, The Teachers’ Institute, Ward School Teachers’ Association, City Teachers’ Association,” American Journal of Education 40 (September 1865): 495-96.

[12] Samuel E. Staples, Normal School and their Origin: A Paper Read at a Regular Meeting of the Worcester Society of Antiquity June 5th, 1877 (Worcester, Mass.: Printed by Tyler & Seagrave, 1877), 2-4. http://archive.org/details/normalschoolsan00massgoog

[13] Our Common Schools,” New-York Daily Tribune, February 4, 1843: 1.

[14] Fifteenth Annual Report of the Board of Education of the City and County of New York for the Year Ending January 1, 1857 (New York: Wm.C. Bryant & Co., 1857), Appendix, 38.

https://archive.org/details/annualreportofbo1518newy

[15] “Teachers and the Normal School,” New York Daily Times, October 12, 1853: 4.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Thirteenth Annual Report of the Board of Education of the City and County of New York for the Year Ending January 1, 1855. (New York: Wm. C. Bryant & Co., 1855), 53.

http://archive.org/details/annualreportofbo00newy_1

[18] Twenty Seventh Annual Report of the Board of Education of the City and County of New York, for the Year ending December 31, 1868 (New York: Evening Post Stream Presses, 1869): 52.

http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nip.32101067944346;view=1up;seq=9

[19] Twenty Eighth Annual report of the Board of Education of the City and County of New York, for the Year ending 31st December, 1869 (New York: Printed by the NY Printing Company, 1870), 50.

http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nip.32101067944353;view=1up;seq=7

[20] Clare Bunce, “The Normal College of the City of New York,” Harper’s Bazaar 25, no.4 (1892): 70.