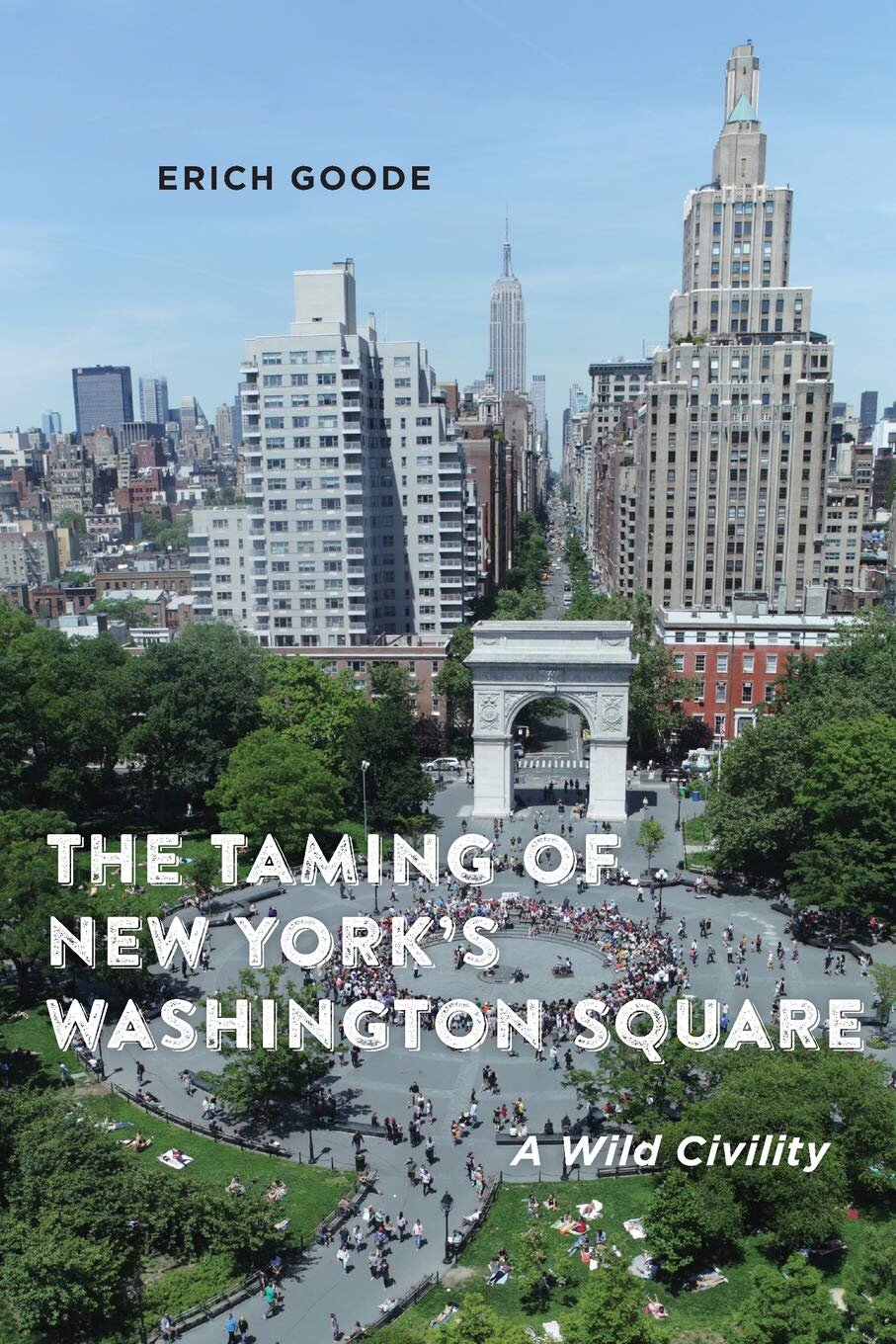

The Taming of New York’s Washington Square: A Wild Civility

Reviewed By Stephen Petrus

Even during COVID-19, New York’s Washington Square Park maintains its quirky identity. Chances are on a visit you’ll still encounter locals, tourists, buskers, sunbathers, NYU students, dog walkers, chess players, homeless people, petty drug dealers, and maybe even Fartman, Pigeon Man, and the Squirrel Whisperer. In the 9.75 acre square in Greenwich Village, the hodgepodge of nonconformists, eccentrics, and iconoclasts make the park great. They give Washington Square an offbeat, permissive identity. Though some visitors violate park rules and ordinances and commit misdemeanors, such as alcohol consumption and cigarette and marijuana smoking, few serious crimes occur in Washington Square. The park offers a rich case study in safety and tolerance. In The Taming of New York’s Washington Square, local resident and sociologist Erich Goode contends that the park’s visitors keep violent crime low through informal and interpersonal social control.

The Taming of New York’s Washington Square: A Wild Civility

By Erich Goode

New York University Press, 2018

297 Pages

Goode, Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Stony Brook University, investigates the responses toward deviant behavior in the park through observation and interviews. He conducted the bulk of his research from 2015 to 2017, spending countless hours in Washington Square passively observing individuals and taking notes. He interviewed sixty people for their views on 22 park violations, including littering, sleeping on benches, and playing amplified music. As Goode analyzed his particular data, he focused on the general question of civility in the park. How does a motley assortment of characters get along in Washington Square?

For starters, formal agents of social control play a role. The city’s Department of Parks and Recreation maintains a unit of unarmed, uniformed Parks Enforcement Patrol (PEP) officers to enforce rules and regulations. They walk through the park at irregular intervals between six in the morning and midnight. The New York Police Department patrols Washington Square infrequently. To supplement officers on foot, the NYPD installed nine surveillance cameras throughout the park. And New York University Public Safety personnel make rounds occasionally.

More important than official law enforcement, Goode argues, is the informal and interpersonal social control created by the park’s visitors. Violations of park rules occur daily but rarely do officers crack down on the culprits to the full extent of their powers. What typically happens is that park-goers simply ignore or walk away from the scofflaws. In some cases, they’ll reprimand them. Occasionally, PEP officers will issue a warning or make an arrest. If a crime has occurred, the NYPD will apprehend and take a suspect into custody. But, in Washington Square Park, aggressive policing doesn’t happen often. Goode rightly observes that in this environment, violations of the law don’t always trigger moral or social condemnation. There is tolerance for unconventional behavior. Frequently, park-goers accept or overlook conduct that society considers to be inappropriate. And yet, these infractions, even when they rise to the level of misdemeanors, hardly ever result in more serious crimes.

Goode’s observations of deviance are astute but he doesn’t probe the origins of the taming of Washington Square. How did it become safe in the first place? The book’s title suggests that the process is ongoing. We don’t get historical analysis but only a portrait of Washington Square during Mayor Bill de Blasio’s first term (2014 – 2018), when crime was low in New York City. It wasn’t always this way, of course. Crime rates changed in the park. Following the fiscal crisis of 1975, it was often dangerous and uninviting. In 1983, for example, as journalist Howard Blum reported in the New York Times, Washington Square was decidedly unsafe. In the first 10 months of the year, police made 545 arrests and issued 2,764 summonses in the park. Most offenses related to drug dealing. Community leaders and law enforcement speculated that the illicit activity partly resulted from the lack of lighting. Of 71 lights in the park, 46 did not work. Crime fluctuated throughout the remainder of the decade, declining in 1987 after the implementation of measures to stem the crack epidemic in the neighborhood by the local police precinct in collaboration with Village residents and NYU officials.

But in Goode’s account, safety in Washington Square is primarily a result of park visitors exercising informal social control, not a function of municipal policy. In fact, he claims, Washington Square undermines the influential “broken windows” criminological theory of social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling that unchecked minor offenses lead to felonious crime. In their 1982 article in The Atlantic Monthly, Wilson and Kelling argued that comparatively slight but seemingly pervasive nuisances in public spaces made cities unattractive and undesirable. If tolerated and neglected, small problems, such as broken windows and vandalism, invited more serious crime. It was the responsibility of city governments, they concluded, to fight petty crime with the same intensity as dangerous offenses.

Surprisingly, Goode does not engage further with the “broken windows” theory, though it is central to his argument. The crime rate in Washington Square dropped sharply in the 1990s when Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his Police Commissioner William Bratton put into practice aggressive policing techniques based on “broken windows” ideas. As historian Themis Chronopoulos explains in Spatial Regulation in New York City, Giuliani and Bratton cracked down on “disorderly” individuals in the city, especially in tourist districts, targeting drunks, addicts, panhandlers, loiterers, prostitutes, rowdy teenagers, graffiti writers, the mentally disturbed, and squeegee men. Most people arrested were young men of color and low income. The strategy, called “zero tolerance” in tandem with CompStat, a statistical approach to mapping crime geographically, had striking results. Crime in New York plummeted. But zero tolerance also led to an increase in civil rights abuses and police brutality and contributed to the expansion of the mass incarceration of African-American men. In Washington Square, the heavy-handed policies included the installation of surveillance cameras and the regulation of artists and vendors. Goode does not offer his views on “broken windows” policing in the park in the 1990s.

Goode does grapple at length with another luminary in urban studies, Jane Jacobs, author of the classic The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). Her concept “eyes upon the street” on crime and safety remains influential among urban criminologists. In essence, Jacobs contended that sidewalks used fairly continuously by pedestrians tend to be safe. These pedestrians, both residents and strangers, form networks of voluntary controls and in effect act as natural surveillance. Police are still necessary but they are secondary in the maintenance of street peace and safety. To create lively sidewalks, Jacobs advocated mixed-use developments of residential, commercial, and industrial buildings on streets to bring together residents, shoppers, and workers throughout the day. Famously, Jacobs cited her own block on Hudson Street in the West Village as an example par excellence of her vision, poetically describing the continuous flow outside her door as “an intricate sidewalk ballet.”

Though Goode recognizes value in “eyes upon the street” as a deterrent to serious crime, he is critical of the Jacobs model for not considering intrusive individuals casting judgment on “harmless lifestyle deviancies,” suggesting that people in her day would not have accepted gay, lesbian, and interracial couples. But this is beside the point and out of context. In 1961, these types of relationships were considered taboo in American society. Jacobs at once offered a critique of modern urban planning and a paradigm for safe and exuberant city neighborhoods. Her writing did in fact create empathy and encourage readers to see interrelated components of community. She reflected, “The safety of the street works best, most casually, and with least frequent taint of hostility or suspicion precisely where people are using and most enjoying the city streets voluntarily and are least conscious, normally, that they are policing.”

The Taming of New York’s Washington Square offers ideas about safety and tolerance in public spaces in cities at a time when Americans are passionately debating the role of law enforcement in society. There’s a growing call nationwide to defund police departments and reallocate resources for social services to poor and working-class communities. Black Lives Matter protesters and their allies are demanding institutional reform and an end to punitive methods in criminal justice. New York’s Washington Square Park, Erich Goode demonstrates, presents a model that prioritizes the responsibility of citizens in maintaining civility and relegates police to a secondary role. The writings of James Q. Wilson, George L. Kelling, and Jane Jacobs provide Americans across the political spectrum different approaches. The nation is at a crossroads.

Stephen Petrus is a historian at the La Guardia and Wagner Archives at La Guardia Community College. He is co-author of Folk City: New York and the American Folk Music Revival, published by Oxford University Press in 2015.