What Did New Yorkers Read in the Gilded Age? Looking at the Armstrong Records

By Erin Schreiner

West 10th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues was an exciting place to live in the last decades of the nineteenth-century. Mark Twain lived on the 5th Avenue end of the block at number 14. At number 51 stood the Tenth Street Studio Building, which housed creative tenants like John La Farge, William Merritt Chase, Winslow Homer, and many others. Directly across the street at number 57, the stained-glass artist David Maitland Armstrong lived and worked with his wife and children -– daughters Margaret and Helen were successful artists as well –- in their studio-home. And just around the corner, the New York Society Library stood at 67 University Place.

The Armstrong family, c. 1910. Image from Wikimedia Commons.

The Armstrong family may not be the best-remembered residents, but an image of a lively and active family comes to life when you look to their use of the Library. The Library’s circulation records, which survive with some gaps from 1789 to 1909, contain dated entries of the books borrowed under the family account. These records reveal the reading habits of a highly productive family of educated, artistic, and adventurous men and women, and open a window into the private life of a New York family of the Gilded Age.

So, who were the Armstrongs? David Maitland Armstrong was an American diplomat turned stained-glass artist, who married Helen Neilson Armstrong (1845-1937) in 1866. His eldest daughters, Margaret Neilson Armstrong (1867-1944) and Helen Maitland Armstrong (1869-1848) were also artists; Margaret was a celebrated book designer and author, and Helen worked for Louis Tiffany and then with her father designing and executing commissions for stained glass windows. Four more children were also living in the household at the turn of the 20th century: teenagers Edward (1874-1915), Noel (1881-1938), and Marion (1880-1957), and baby Hamilton (“Ham,” 1893-1973).

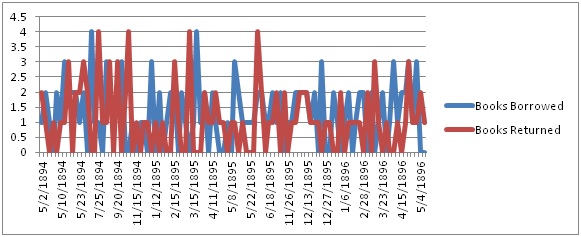

Between 1894 and 1896 -- the set of records I transcribed for this little study –- the seven reading members of the household borrowed 138 books for an average of 10 days at a time, although most books stayed out for just three. Trips to the Library were frequent but irregular; there is no set pattern to their visits, but rather a constant flow of books back and forth between University Place and 10th Street. Books were borrowed and returned as needed. More books were borrowed on a single visit and stayed out longer, for example, during the summer and winter holidays. In the spring and fall, trips around the block took place at least once a week, and some books went there and back on the same day.

Of the 138 books they borrowed, 80 percent were works of fiction. Canonical authors are well represented in their reading: Jane Austen, Anthony Trollope, Rudyard Kipling, George Meredith, Henry James, Thomas Hardy, Mark Twain, and Arthur Conan Doyle were all borrowed multiple times. Trollope's The Belton Estate, Austen's Emma, Mansfield Park, Northanger Abbey, Persuasion, and Sense & Sensibility, Kipling's The Jungle Book and Under the Deodars, Doyle's My Friend the Murderer, Stark Munro Letters, and A Study in Scarlet and Twain's Tom Sawyer all circulated, although to whom, exactly, is unclear as the records don't distinguish borrowers on the family account. Recent novels by their now lesser-known contemporaries during the 1880s and 1890s were also popular. Romances and family dramas by Dorothea Gerard, Blanche Willis Howard, Lucy Walford, and Margaret Deland all circulated. Historical fiction was popular, too: William Westall's For Honour and Life, J.H. Shorthouse's John Inglesant & Sir Percival, Charles Reade's The Cloister and the Hearth, and Edward Lytton's The Last Days of Pompeii went out, as did Thomas Malory's La morte d'Arthur (in English, twice). The family read through the works of several authors over the course of a few months, and in some cases –- Jane Austen is a notable example -– throughout the two-year period.

While poetry and non-fiction only amounted to 20 percent of the Armstrong's reading during these years, the books borrowed help to fill out the picture of the intellectual life of the family. Tennyson's poetry makes a few noteworthy appearances, as does Edmund Gosse's The Jacobean Poets, Lionel Johnson's The Art of Thomas Hardy , and two other books of criticism. At least one member of the family took a strong interest in Napoleon's life and military campaigns.

Perhaps the most exciting pieces of non-fiction, however, are those that reflect the family's artistic pursuits. Henry James' Picture and Text, a short work published in 1893 on the relationship between text and illustrations, went out for two weeks in the summer of 1894. This was almost surely a choice of Margaret's, coming into her own as a book illustrator and binding designer. During that year her work was praised in newspaper columns nationwide, and publishers' advertisements highlighted her as designer in new publications. In May of the following year P.L. Jacobs' The Arts in the Middle Ages went out for five days. This seems like an obvious choice for either David or Helen junior, who were also mentioned in the press several times (though not as often as Margaret) in connection with their work.

Circulation Records for the Armstrong Family 1894-1896, Institutional Archive, New York Society Library. For full-size images of these records and more from this period, see the Flickr Gallery here: https://www.flickr.com/photos/nysl/sets/72157669311703411/.

Although he was just a baby in 1894, Hamilton Fish Armstrong's memoir, Those Days can add more meaning to the family's borrowing history. The book describes his family life during childhood, and ends long before his career as editor of Foreign Affairs. His frequent mention of books and reading, both in private and in the shared domestic setting, demonstrate the centrality of literature to family life. Books and art were discussed at meals, and Hamilton makes frequent mention of his older siblings guiding his reading. Marion taught him to read, and Helen recited poetry to him at bedtime; he specifically mentions a poem from Tennyson's The Idylls of the King, a book borrowed on December 26, 1895. Helen appears again when he describes his young fondness for the historical adventures of G.A. Henty. "To get me away from Henty," he wrote, "Helen offered me twenty-five cents for every Dickens or Scott novel that I would read" (84). Helen also read aloud from La Morte d'Arthur, another book borrowed from the Society Library. Anecdotes such as these portray Helen as a leader who initiated her siblings into the world of culture, particularly as it was defined by art and literature.

In the absence of a broader study of the history of readers and reading in New York City, we can turn to a study of American readers and reading in the 19th century to see how the Armstrongs fit in. In Well-Read Lives (2010), Babara Sicherman shows how books played a crucial role in the lives of Gilded Age women -- more specifically, women with careers -- through studies of familial and individual reading practices like those of the Hamiltons in Fort Waye, Indiana. Without diaries and extensive collections of letters, we don't know how Margaret, Helen, Marion, and Helen senior felt about the books they read. But we know for certain that reading held a central place in the family, and books surely influenced not only their creative work, but also their views of themselves as intelligent, capable women, driven to succeed in the public sphere. Helen successfully ran the family's stained glass business long after her father's death; Marion published collections of poetry; and Margaret designed book covers, wrote novels, studied botany and published the first field guide to western wild flowers after an extended expedition to the west with three female companions. In light of the model set by Sicherman, it seems reasonable to suggest that the reading habits that these women learned at home and nurtured at their neighborhood library were integral aspects of their development as individuals. The same can surely be said for the success that Hamilton enjoyed in his adult life.

Circulation records alone cannot tell the full story of the history of readers and reading in New York City: letters, diaries, and personal accounts are essential pieces of the historical puzzle that add nuance to these histories. They can, however, provide information about individuals and large groups of readers, filling in facts about books read through time that the readers themselves may have forgotten or left unshared. Circulation records can also reveal the names of readers whose lives have been obscured in the passage of time. Even this brief snapshot of the Armstrong family shows that a lively, shared intellectual life was an important part of life for one New York family. There's still much more to learn.

Erin Schreiner is Special Collections Librarian at the New York Society Library. This year, the Society Library launched City Readers, and open access database of its digital collections featuring transcribed copies of circulation records from 1789-1805.