A College Grows in Brooklyn

By Rachel A. Burstein

With hipsters flocking to Williamsburg and Bushwick, and homes in Park Slope and Cobble Hill now sometimes fetching higher prices than prime realty in Manhattan, it seems hard to imagine Brooklyn playing second fiddle. But the decades-long debate over if and how to create a new, public college in the borough brought ancient, simmering tensions in New York to a head at the beginning of the 20th century.

Less than a generation removed from the 1898 consolidation of New York City that brought the cities of Manhattan, Brooklyn, Richmond (Staten Island), Queens, and the Bronx together under a Manhattan-based government, the public discourse over the creation of Brooklyn College (now a part of the City University of New York system) reflected a borough wrestling with its new status in a unified New York, as well as a changing identity hastened by an evolving political landscape and a rapidly growing population. Old-guard civic leaders, businessmen, politicians, Brooklyn-based City College students, members of the press and others used the prospect of a college in their borough to paint their vision for—and anxieties about—what this new borough of Brooklyn would become in future decades.

Despite having the nation’s third largest population, after Manhattan and Chicago, Brooklyn did not have a public university of its own. By 1917, City College (CCNY)—the well-regarded Manhattan-based public university—began offering an evening program in Brooklyn to serve more of the city’s residents on their home turfs, the first of a number of planned centers throughout the boroughs. While students—nearly a third of whom lived in Brooklyn—welcomed the chance to reduce long commutes, residents and leaders had very little involvement in the project.

It was only with the founding of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce in 1918 by the borough’s business elites that that began to change. The Chamber’s leadership saw the establishment of a Brooklyn-based university as a chance to provide the borough with a prestige stripped away by consolidation, attracting new clients and encouraging existing companies to relocate. The Chamber was committed to boosting pride, burying “knocks for Brooklyn” once and for all.

As elites themselves, Chamber leaders preferred an institution serving non-immigrant, elite students, rather than providing new opportunities to the borough’s marginalized populations.

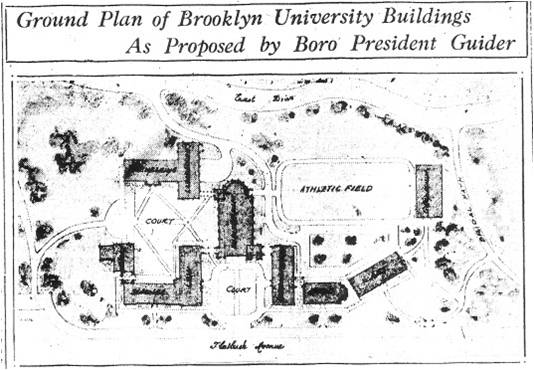

Brooklyn’s politicians felt this resentment even more than Chamber of Commerce leaders. For them, a mere branch of CCNY, without any oversight by Brooklyn officials or a faculty independent of City College, was not enough. Reflecting outsized political ambitions, and based on hyperbolic estimates of Brooklyn’s current 1925 population, Joseph A. Guider, the Borough President, argued that “what Brooklyn wanted was a university of her own that would take rank with any in the country.” Noting that “many men and women from Brooklyn have attained eminence and distinction in their various professional callings,” Guider believed that Brooklyn’s residents together demonstrated the area’s intellectual prowess and potential.

With an appeal to the New York State Assembly to appropriate funds for a borough-operated public university to be constructed in Prospect Park, Guider served notice that Brooklyn was not going to play second fiddle any longer–and that in the process, borough officials whose egos were bruised in the aftermath of consolidation would have some responsibility and decision-making power restored.

Emanuel Celler served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1923 to 1973

But the Chamber was also pragmatic, supporting very different visions advocated by power-brokers who could help make a Brooklyn-based university a reality. Congressman Emanuel Celler was one such ally. Celler’s understanding of the value of a new institution was far more inclusive than the Chamber’s. “We want in Brooklyn men and women who can appreciate Beethoven as against Irving Berlin; who prefer George Elliott to Snappy Stories…who will, by virtue of their humanizing training at college, in the words of DeFoe, be ‘less brutish,’” Celler wrote in the organization’s newsletter.

For Chamber leaders, a different sort of university was better than none at all. Acting strategically, they first encouraged CCNY Trustees to establish a full Brooklyn campus, arguing that without such a presence the College was not making good on its commitment to serve the entire City. It was essential that “residents have conveniences equal to those of persons living in Manhattan,” Chamber leaders argued, betraying the resentment of living in Manhattan’s shadow, decades after consolidation.

Chamber leaders reacted negatively. If it was really to be a “university of Brooklyn and for Brooklyn,” one member argued, it should be “controlled by Brooklyn citizens… independent, and not subject to a changing policy, dictated by those in temporary control”—a critique of both Guider and CCNY officials, and a tacit self-endorsement for rule.

The Chamber was not the only one to balk at the proposed governance structure. Though denying involvement in its construction, City College officials supported a competing proposal from a Manhattan Assemblyman, which called for the establishment of a Board of Higher Education to govern all public colleges across a system, including a new Brooklyn college. The Board would include representatives from City College and Hunter College’s Board of Trustees, with the remainder appointed directly by the Mayor—shifting the nexus of power back to Manhattan (and from Democrats like Guider to Republicans like the Assemblyman who introduced the legislation).

Forced to choose between giving up any semblance of control, and going with a plan that empowered Manhattanites, Chamber leaders reluctantly chose the former. But when Guider’s proposal was defeated in the State Assembly, Chamber leaders were forced to pick sides again. They agreed to lukewarm support for the Manhattan-backed proposal, reasoning that an imperfect institution was better than nothing. As one Chamber official put it, a “refusal on the part of Brooklyn to accept [the] measure would be… an act of almost suicidal folly.”

The two sides—now based more on party affiliation and class divide than borough affiliation—came to a head with efforts to convince Governor Al Smith to sign or veto the latter legislation, establishing a Manhattan-heavy, City and Hunter College-dominated, and mayor-controlled Board. Tempers flared, with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle characterizing the proposal as a form of “alien control.” Guider viewed the plan as “part of a larger effort “to hamstring Brooklyn,” possessing “no more substance than an empty egg shell.”

Ultimately, the Governor—himself a Tammany man—was persuaded, urging the Assembly to go back to the drawing board, and buying time for Democrats in Brooklyn to work out a more favorable compromise.

Dispirited lawmakers, CCNY officials, and civic-minded Brooklynites worked on the problem over the remainder of 1925 and the winter of 1926. In order to garner the governor’s signature, new legislation would have to represent the interests of intensely independent Brooklyn Democrats on the one hand, and fiercely controlling City College administrators and Manhattan Republicans on the other. As it had done so many times in the past, the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce tried to mediate a compromise between the extremes. This time it used its class position as leverage with Republicans and City College officials, and its borough solidarity as leverage with Democrats. That formula proved successful.

Chamber directors tried to keep the issue alive by actively seeking out opinions from other local organizations for the first time, sending a survey to 90 civic organizations to gauge opinion on the proposals that had circulated in the past. In so doing, they sought to correct a problem poignantly depicted in a January 1926 cartoon showing a ribbon of “loose co-ordination” giving way to a freefall of “plans of civic bodies,” held by a female shopper representing Brooklyn under the heading, “Tie them tighter and make more progress."

The Chamber also devoted significant space in its weekly magazine to advocating for a public institution of higher learning of any sort in Brooklyn. The editors exchanged their classist rhetoric of the past for the equal opportunity arguments made by Celler. Thus, Major Joseph Caccavajo, a population statistician, argued that “while talking about higher education we should not forget that here in Brooklyn there are nearly 100,000 persons, 10 years of age and over, who are entirely devoid of any education and in our midst,” a fact borne out in high illiteracy and non-English speaking rates.

CCNY administrators also changed their tune. Recognizing that support from Brooklynites was necessary for the creation of a branch institution, the typically bombastic Frederick B. Robinson, Dean of City College toned down his rhetoric. In a report stating that Brooklyn supplied 35.7 percent of day session students at CCNY (compared with Manhattan’s 35.5 percent and the Bronx’s 24.8 percent), he gave publicity to the issue, leaving others to offer the political spin. Faced with an ever-deepening overcrowding problem, City College officials reached out for compromise. The result was the establishment of a committee of prominent Brooklynites to investigate the problem. Reflecting the importance of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce in any compromise, Ralph Jonas, its President, was appointed chairman, an honor CCNY trustees said came at Guider’s “insistence.”

True or not, CCNY’s overtures appear to have appeased the borough president. With his objections leading the way for the governor’s veto a mere six months earlier, Guider perhaps recognized that failure to cooperate with CCNY in formulating a plan for a comprehensive City College day session in the borough would lead to public rebuke.

Many things had changed since the previous year. For one thing, CCNY now presented its case in terms of the urgent need for public higher education in the borough, rather than a mere plan to extend its reach. For another, the Brooklyn residents chosen to serve on Jonas’s committee would have an opportunity to offer input on governance models for the new campus: the focus of Guider’s opposition to the proposal vetoed by Smith. Given these shifts, it would have been difficult to reject the approach. Astute politician that he was, Guider vowed to cooperate, serving as the honorary chairman of the committee and working with Jonas to select its appointees.

Tellingly, the committee itself was composed primarily of Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce officers and other elite citizens, including a former Secretary of Commerce under Woodrow Wilson and the current Dean of the Brooklyn Law School. Still, the large committee included some representatives from other civic organizations, correcting a long-standing inability to coordinate programs across the borough. Indeed, the Chamber’s weekly journal hailed the first meeting as “unique in the history of the community” because it “gathered together men and women representing all creeds and sections” and placed “leaders of civic organizations,” “prominent educators,” “business men,” and “officials of the nation, state and city” alongside one another for the first time. Appointees had affiliations as diverse as the Brooklyn Heights Association, Brooklyn Technical High School, the Boy Scouts of America, Long Island College Hospital, the Brooklyn Bureau of Charities, the Knights of Columbus, the Brooklyn Jewish Center and the Brooklyn Music School Settlement. Altogether, committee members numbered over a hundred.

This new willingness of civic organizations to organize together, and the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce’s role in coordinating these efforts, was not lost on observers. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle editorial staff noted, “During the past few years the better elements of Brooklyn and its larger institutions have become integrated and unified. They have learned to express their community as well as themselves.”

With allies in politics and the press firmly established, Jonas’s committee worked with state legislators to create a bill that would meet with the governor’s approval. Compromise came in the form of a new bill with sponsorship across regional and party affiliations. The legislation proposed a Board of Higher Education temporarily composed of members of the City College and Hunter Boards with three Brooklyn members. Vacancies would thereafter be filled in proportion to each of the borough’s respective populations. In this way, Brooklyn would come to assume more power than had been afforded under the previous bill and the possibility of expansion to other boroughs would be protected. With dissent limited to a few outliers, Governor Al Smith signed the bill into law in April 1926.

The legacy of this action reverberates even today. The creation of a Board of Higher Education and the establishment of Brooklyn College a few years later paved the way for the development of a comprehensive public education system with distinct institutions across the five boroughs. It also highlighted tensions inherent in consolidation, and the role of politicians and civic organizations in negotiating those differences. The question of who controls public education in New York, and for what purpose, continues to provoke vigorous debate. Allocation of resources between institutions, and for different types of students within (or denied admittance to) the system, remain open questions, as in the past.

But it is the rise and fall of different geographic areas of the City—and the power of particular individuals, groups and institutions within those areas—that is the most enduring legacy of the debate. At a time when certain Brooklyn addresses connote power and status, we are wise to remember that such designations are inherently political. They are negotiated and made, not historical accidents.

Rachel Burstein holds a PhD from The Graduate Center, CUNY, and develops K-12 social studies curricula for an educational technology company.