Archiving for Access and Activism: An Interview with Interference Archive

By Emily Brooks

Interference Archive is a Brooklyn-based organization that collects and houses materials created as part of social movements. These materials, which include posters, flyers, publications, buttons, and much more, are stored and exhibited in an open stacks archival collection at 314 7th street in Park Slope. In addition to organizing and maintaining the collection, which is open to all, Interference’s volunteers also showcase the archival collections through exhibits and various community events aimed at supporting contemporary activism. This spring, I sat down with two of Interference’s volunteers, Ryan and Nora, to talk about how the space works and the role they see the archive playing in connecting social movements of the past with those of today.

Interactive piece of current exhibition where visitors can add a photo and message. Photo credit: Nora Almeida.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

I wanted to start by asking both of you when and why you got involved with Interference Archive?

Ryan: I think it was three years ago because it was right after the election. So, as the shit was spiraling off the fan I saw an email that was announcing an exhibition that Interference was having in the old space on prisoner artwork in a calendar. It was the launch of that. And I saw the name “Interference Archive” and I thought I love archives and I want to get more involved and now seems like a very good time. So, I came to the exhibition, checked it out and just kind of emailed afterwards and just said I love what this organization is doing and I’d love to take part.

Nora: I got involved probably 4 or 5 years ago now, partially because I attended an event and I live in the neighborhood. I came to some events and then got on the volunteer list and then the first thing I really got involved in was a James Baldwin reading group that we did. It was part of an NEH Grant funded project all over the city and they were looking for discussion leaders. Since I do a lot of teaching, and felt like I want to read a lot of James Baldwin and talk about it with people, that sounded pretty fun. So, I did that and a few people involved in that were part of the education working group here so I got involved in doing more stuff that the education working group was involved in.

How many volunteers would you say are involved and what is the organization’s structure?

Nora: I would say around twenty core volunteers. Everything is done by working group. I am in the education working group. Every exhibition has a working group. I also do occasional staffing and stuff with the propaganda parties which are really fun. Those are when we make materials like posters, banners, tshirts, and buttons for current organizing campaigns. We did a lot of them in the summer. We had an exhibition on the history of Agitprop, and we partnered with a bunch of local organizations and made propaganda for their causes. I helped with that exhibit and Ryan helped organize the Hate-Free Zones propaganda party. We did another one with Families for Safe Streets. We also have a podcast so there is an audio working group, which is very cool and people should check that out. We have a website working group and a cataloging working group. They do cataloging parties to get together and do that work and make it more fun.

Ryan: The groups are sometimes organized based on projects. So, for example I am part of the mobile archive working group, which is another informal working group that runs through an email thread.

How do the volunteers decide on what the exhibitions will be?

Nora: Sometimes it comes from an outside source, when someone is interested in collaborating with the archive. For example, we did an exhibit on the radical press in the 1970s and that came from someone who had a crazy personal collection. The Australian poster art collection that just closed similarly came from the personal collection of Alison Alder who worked with a bunch of graphics collectives in Australia and was friends with someone here. So sometimes there is an organic connection like that. Other times is more of an intentional reaching out. I have never been involved in conceptualizing an exhibit. I have always been the person who said I would help with that exhibit!

Ryan: The other two ways I have seen the ideas emerge is in an admin working group meeting. We will pitch a few ideas and then shoot them out to the listserv and see if anyone has any objections to any of the ideas or a strong preference for one over another. And then we also meet quarterly for volunteer retreats which are sometimes just here, we don’t actually retreat away from the space, but those are times that we bring it up as well and talk about possible exhibitions then.

I first became aware of Interference when I moved to Brooklyn and started grad school seven years ago. I’m a historian so I’m in the archives a lot, but when I first came to Interference I was really struck by how different the experience of being in this archive was from working in other institutional archives. And so I’m curious if you have experience in other types of archives.

Ryan: I work primarily with private photography archives. Photographers, collectors, artists.

Nora: I am a trained archivist and an academic librarian. I have worked in other archives including the New York branch of the National Archives. There is a big difference between how we organize things here and how traditional archives are organized. Part of that has to do with the kind of materials that we collect, which are not archival in a technical sense, or in the way that many archives think of archival materials as being unique objects. We only collect things that were created for public consumption in multiples. A lot of the things that we have might be the only one left or the only one that anyone knows about, but they are still things that were mass produced like posters, newspapers, ephemera like flyers. We have a lot of serials, zines, things that were created basically to distribute, and then they were distributed and then we have those things. The way in which we are able to make things accessible here is in part about honoring the spirit in which the material was created.

Interior image of current exhibition. Photo credit: Ryan Buckley

The archive is partly oriented around the question of what do the materials want.

Nora: The archive is organized with open stacks so people can come in and go through boxes. Volunteers catalogue things and work with materials. There is always a preservation vs. access kind of question in any archive, but we definitely privilege the access because that is why the materials were created. That is why we display materials on our walls and do the events that relate to the materials that we have and to ongoing social movements.

How do you acquire most of your materials?

Ryan: We don’t have an acquisitions budget or intention even, we get things as they are donated. There were some founding collections that gave us the base for this, but since then it has been the community that sees that we have something that they could also contribute to, or that there is a gap that could provide some insight towards. So, it is sort of becoming more and more a community archive as it grows.

Do you ever turn anything down? Or do you go through donations and sometimes decide not to keep some things?

Ryan: We recently stopped accepting books basically for the time being. We completely filled our space and we are doing a project to find out what we have. Then from that list we are working to find out what is already accessible in the community. So, if we have a copy of something that is at the Brooklyn Public Library we will consider if we need to also hold that item. I have culled things out of donations that people have dropped off that did not fit with the collecting mission of the archive. When people drop stuff off we tell them that it is likely that not all of their donations will be maintained at the archive.

Nora: Yeah and we have space limitations. We recently did a de-duplication process for a lot of our pamphlets and serial publications. We also will not accept things that people want to put access limitations on. So, if someone is interested in donating something but they only want people to be able to view it in a certain way because of preservation concerns then we just say we are not for you.

Have there been any particular finds or something that was donated that was memorable for you?

Ryan: Going through the zines for me was a really exciting experience and the OSPAAAL (Cuba’s Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America) posters are really beautiful.

Nora: Our posters and pamphlets are really one of the easiest ways into the collections. One of the things that I do when classes come here and they don’t have a focus is pull from one of our pamphlet collections that I find particularly compelling. We have pamphlets here that were created by a press called Temporary Services. I think they are Chicago-based. They produced one pamphlet about things that prisoners have tried to patent. They have others that document and cite public actions. Some of them are just be photos of people doing provocative things, or directions on how to disrupt a meeting. I like how it is a press, but it also intersects with reality in a way that is agitational. I am interested in performance and performative dimensions of social activism so I have intentionally looked for things that are in that vein.

Ryan: I totally forgot—there is a box of 3D objects.

Nora: Oh yes! The 3D objects are amazing!

What’s in the box?

Ryan: Zip tie cuffs that were used at Occupy, clippings of a fence from a barricade that was put up, and other items like that. These things just have such an aura to them that the printed materials don’t necessarily have as much.

Nora: And they are mysterious. Because if you don’t know the story behind them you just feel like, what is this? We did an educator workshop about working with primary sources and we had everyone pick something from that box and discuss it. It was an opportunity to think about who made this, and what context did it seem like it belonged to, and what information could you determine just from looking at it? Three dimensional things and ephemera itself can be really decontextualized.

Right, if you don’t have the background in the material culture that it is from you have no way of reading it. One thing that I like about this archive is that because it is more accessible and open you can be led from one item or collection to another without a very directed research agenda, which is often not the case in other collections and maybe makes it more accessible. Speaking of accessibility, I wanted to ask who generally uses the archive?

Ryan: In my experience staffing, people who walk by on the street come in a lot.

Nora: We have also been doing more programming for kids. We have radical playdates and have tried to offer free childcare for some of our events so more kids and more families come to the space now. We also get serious researchers and artists. I helped someone who was working on a performance art piece and was looking for inspiration. We did an exhibit on free university and radical education and so we had a lot of educators coming into the space when that was up. So, different people will be drawn to the exhibits, which is one of the reasons why we put them on. But all sorts of people. And we do get a lot of class visits. High school, college, sometimes visual arts people, but often history, non-profit student groups, or after school programs, as young as middle school.

Ryan: We have also been trying to invert that question and think, who does the archive visit? We are trying to do more outreach and think about what an archive is beyond its walls. And the mobile archive idea is in part based around that. The idea is to take materials out to community events, and town halls, and demonstrations, and vigils and places. We are hoping to have a selection of content that is related to or of interest to a particular group and then distribute or provide access to that content.

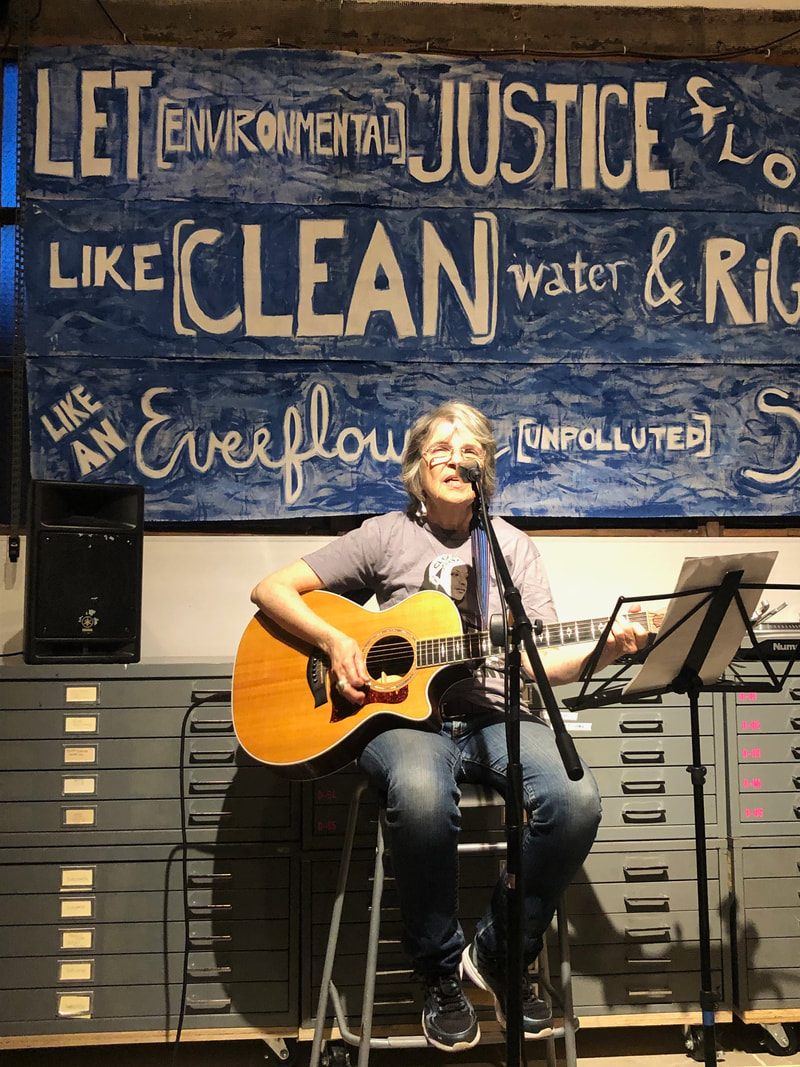

Singer/Activist Bev Grant at a Poor People's Campaign music event. Photo credit: Nora Almeida

What is an example of a place where that has happened recently?

Ryan: Well we are still working on materializing that, but we did take a propaganda party out to the New School and did some work there. For a few years now we have been going to Red Hook Fest and we take materials related to concerns that community might have like affordable housing or cop watch stuff like that.

Nora: We did a big propaganda party in the park and with the upcoming party for May Day I was really interested in bringing in people working on labor and housing justice in Gowanus. Gowanus is getting rezoned and one of the reasons that the archive lost its original space is because of the changes to the landscape in that neighborhood. And we are still on the border of this neighborhood that is getting reimagined. So, we wanted to bring people working on those issues in. We do block parties to try to plug into our local neighborhood and we have tabled at other types of events. I tabled at an anti-gentrification summit a couple of years ago. We usually do the anarchist book fair at Judson Memorial Church and we have also done exhibits outside of the archive. We have loaned stuff to other institutions and we did a whole exhibit that was focused on materials produced by Justseeds which is a print making collective that a few of the volunteers here are involved in. We did a whole exhibit of Justseeds materials alongside with other archival materials contextualizing the issues that the posters were representing at SUNY Purchase.

In my experience as an educator and an activist I feel like people are really excited about learning activist history particularly when they can do so through cool visual materials. What kind of response do you get from activists at these events?

Ryan: People are really excited and they love engaging with the materials.

Nora: And making new material. I think that is huge. For this propaganda party we are working with Lane Sell from Shoestring Press who just approached us about wanting to do May Day. He and Jen, who is another volunteer here, and I talked about curating some material for him to look so he could be inspired by old stuff to make something new specific to this issue. And I have been trying to reach out to people who are already organizing around this issue. And I am going to go to the zoning scoping hearing to hand out flyers. I hope that people come from the neighborhood who might not know about the space and who are angry that the neighborhood is getting rezoned and want to make a poster or T-shirt to wear around to inform their friends and neighbors in Community Board 6.

So, you mentioned your move from your old space into this space and that was driven partly by the rezoning and by financial needs. Where do you get your funding and how does money work for the group?

Ryan: We are all volunteer run so we don’t have a staffing budget. Everything that we do that is nonoperational is through grants. For this exhibition we are each sponsoring some of the new material that we are producing for it. So, every person is kind of buying a print that we are producing. But we keep the lights on through sustainers. So, we have monthly donors that give 10-50 dollars a month, mostly ten.

Nora: We also usually do an annual fundraiser and we do ask for donations from institutions that are bringing classes for a visit and then we will curate material for them. So often part of the wrangling for class visits is seeing if educators can get funding from their institution for the visit in an effort to divert institutional funds to a non-institutional space.

Ryan: We also pass a jar around at events.

Nora: Our events are free so we like to do that and we let people know that is part of how we keep the space going. We also rent out co-working space here which helps with the rent.

Can you tell me a little bit about the current exhibit?

Ryan: Sure. It is a survey of the visual culture of the Poor People’s Campaign 1968 and now, and it runs until June 23rd. The exhibit includes some newspaper and buttons that we had in the archive that speak to the original movement, but we also found a series of documentary photographs that cover some of the people and events of the movement and resurrection citythrough other open source archives. We partnered with the current campaign and asked them to join us in conceiving of the exhibition and in choosing materials and the layout. The exhibition is organized with materials from the two movements facing each other. We displayed materials from the historic movement on one side and items related to the contemporary campaign on the other. Visually, the materials are in dialogue with each other. We are also going to have a lot of public programming for this exhibit while it is open. There will be nights of music and conversations, there will be film screenings, and we are going to do a propaganda party. It’s going to be a lot of fun.

Nora: We do a Wikipedia edit-a-thon for many exhibits. We are trying to do one for every exhibit, but it doesn’t always pan out. I think we have done six. It was one of the first things that I did here. Four times we have participated in Art and Feminism which is an annual global editing campaign to get more women artists represented and more women involved in editing. Because we have been able to get some funding from Wikimedia we have tried to connect wiki edit-a-thons more to the exhibitions so that people can be part of creating information on a platform that is widely accessible and is actually referencing some of the materials in the archive. We use items from our collections to provide information related to articles that need editing or don’t exist yet. We are trying to do one for every exhibit.

Image from current exhibition. Photo credit: Ryan Buckley

Have there been other exhibits in the past that you felt like were particularly successful?

Nora: Well you mentioned the OSPAAAL (Cuba’s Organization of Solidarity of the Peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America). That was a really cool exhibit. It was a very international with posters related to anti-imperialist and leftist liberation movements all around the world and the images were beautiful.

Ryan: I think Agitprop was probably my favorite because it was all about materials that are made to agitate and ignite and its through propaganda. And it kept growing too. We left some blank wall space but then we would do an event with Hate-Free Zones and we would actually fill the walls with what we made. It was a way of connecting the history of what was with the history that we are making. That was inspiring.

Nora: And right before we moved we didn’t have time to put on a big show so we did little mini exhibits, which was very cool. It was called “we are what we archive” or something and it included different thematic sections. One was about the election and we did an election related propaganda party, which was called “Inaugurating Resistance.” That was a cool exhibit because it showcased a lot of different types of material that we have in the archive. We usually produce a catalogue or a print publication that goes with the exhibits and there are some that I think are awesome that I was not here for. The We Won’t Move publication is one of my favorites, but I was not around for that exhibit. I know we put it on with a bunch of other groups that were doing tenant organizing in the city and the book itself includes resources for people who are doing tenant organizing.

Do you have ongoing relationships with groups and people that are doing organizing throughout the city?

Ryan: In the experience of the Poor People’s Campaign we made an effort to reach out and I hope that there will be a lasting relationship that comes out of that. Hopefully they will know that we can be a repository for any materials that they are creating moving forward.

Emily: I know some other non-institutional archives really see themselves as deliberately community building spaces. Here it seems like you are doing some of that but also a bit of a different thing.

Nora: I think there is a lot of overlap. A lot of people who are involved in this space are also involved in ongoing activism. Some people here were really involved in occupy and that is how we got some of the occupy related materials. I know some people are really involved in Transportation Alternatives and Families for Safe Streets and that’s part of how we got involved with them for a propaganda party. One of the other members of the education group does material culture and indigenous studies and I know she was involved with some of the Decolonize This Placeactions. So, I think there is a lot of overlap Maybe it’s not so much that the space has these relationships as that individuals are volunteering at the space as part of their activism and have other connections. There is definitely a connection between people who were involved in movement organizing in the past and are part of the archive because they are invested in how that history is represented now. As volunteers we are intentional about wanting people who are activists now to be part of the process of archiving, describing, and presenting these materials.

Is there anything else you want people to be aware of about the archive?

Ryan: If folks have something that they are working on that is related to social movements or social justice and want to get in touch about hosting an event here we are very open to that. We will do film screenings, or a talk, or other types of events.

Nora: We also do discussion groups and skill shares and other media making demonstrations. If people want to get involved in the archive, get on our volunteer list online and then come to an event or volunteer at an event. Also, all the working group meetings are posted and open.

Emily Brooks is an editor at Gotham.