What Stonewall Means to Me

By Perry Brass

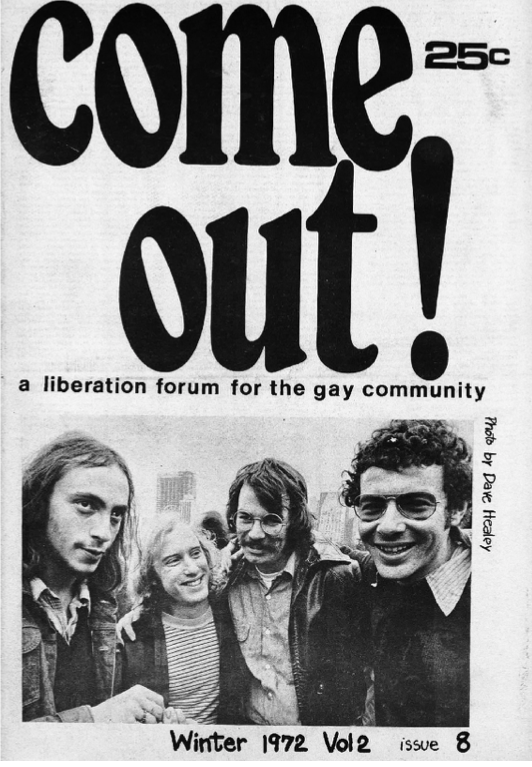

The Winter 1972 issue of Come Out! Perry Brass is pictured at bottom right.

People often ask me if I was “at Stonewall,” and I’m one of the few people who will definitely say, “No.” I was actually around the corner at an old bar called Julius’, when some young men raced in to tell us that “the girls are rioting at the Stonewall!”

It took me a while to understand what that meant: police actions, demonstrations, sit-ins, and marches had become the order of the day due to the Vietnam War, and the social and political unrest of the period. Late the next night, I went out to Sheridan Square and saw what was going on — the broken glass, hundreds of people milling about; the sharp, glaring police “riot lights” that produced their own theatre of the streets. Lots of what we called “street queens” — that is, young gay people who had a street life, something almost non-existent in America today.

They were smiling — so was I — I was ebullient, glowing, really.

Why?

It is very hard for most people to understand the everyday horror and humiliation of being queer in New York then, of being the constant butt not only of jokes, but of threats, of physical and emotional violence, of keeping so much of your life under wraps — hardly even in a closet, but in a sewer — of feeling like a worthless outsider, with basically no legal or ethical rights, or recourse.

I had come to New York after growing up an impoverished Jewish kid in totally segregated Savannah, GA, an extremely conservative city with a strong KKK chapter. I had come out to myself at 16 and to many of my friends a year later.

I realized, soon enough, that the best thing that could have happened to me in Savannah would have been — well, that I would not have been murdered. Later, after moving to New York in August of 1966, a month before my 19th birthday, I quickly experienced a bar raid, and also being openly harassed and then fired at work — several times — for being gay.

I also experienced, in so many instances, the sheer love and embrace of my own outsider gay community. We had a genuine closeness then, and I miss that very much. It was a closeness that overcame differences of class, race, ethnicity, and religion. We belonged to a religious group of our own; a religious group of the heart.

That heart united us when Stonewall exploded that sweltering night on June 28, 1969. And all I can say is, believe it or not, we were all there.

Anyone who believes in the moral rights of the oppressed was there. Or who believes in the Biblical injunction that the oppressed deserve justice was there. Or believes that he or she deserves respect, dignity, and the right to give and receive love. Stonewall has been compared to the Boston Tea Party, the John Brown rebellion, and Rosa Parks’ moment when one woman — and at Stonewall, it was also one woman — said, “I’ve had enough!”

And that is what we all need to feel again and again: that “I’ve had enough!” moment. Just as the Jews say every Passover, “We were all in Egypt, we have all been freed,” every one of us needs to believe that they were at Stonewall, just as they need to act on that moment when they can see, through the strength derived from a shared closeness with others, their own resistance in the face of oppression. We need to see this, because oppression is still here — it is not going away.

What’s going on in Washington, DC, right now; or in Poland; in Chechnya; in Brazil; or Uganda and Kenya; and all over the Middle East as well as in Israel, tells us this. And we need to know it, and work to change it.

In November of 1969, shortly after my 22nd birthday, I joined the Gay Liberation Front. I stayed with GLF for 3 years, one of the most formative and educating experiences of my life. As most people know, the Gay Liberation Front was a “radical” organization. We believed in fundamental economic and governmental changes in America and the world, but more important, we learned to look at the world through what we called a “radical lens.” Radical, meaning going to the root of the problem; the real “issue” as people say now. Also “radical” meaning, understanding power from the viewpoint of the powerless: Who has it, who has taken it from us, and what we need to do to get it back.

We saw that what oppressed gay men was also what oppressed women, especially lesbians: the choke-hold that Western industrial patriarchy has put on us. We saw capitalism as one of the engines of patriarchy, but also saw that patriarchy and sexism were alive and functioning in socialist countries and in Third World, where even big governmental changes had not enacted genuine shifts in ingrained sexist beliefs and attitudes. Later activists used this same “radical” lens to look at LGBT health, sex, relationships, AIDS, marriage, family and other aspects of human life that affect us.

One of the myths about GLF was that we were too young and besotted by the romance of leftist ideology to see the problems of the left. Not true. We’d seen these same sexist motions in all the social movements of the times, including what was at the time known as the “gay movement.”

And we realized there needed to be a lot of work to change it.

Mostly because I was a writer, I worked on the GLF newspaper Come Out! But together with my sisters and brothers, I fought for social justice, for an end to racism, an end to America’s constant cycle of wars, for an equitable distribution of wealth — and for a change in consciousness itself, from passive, cynical, and destructive, to active, moral, and constructive. GLF believed that only a real change in consciousness could change the world: you had to be conscious — alert and alive — to the problems and conditions of the world around you, as well as to its deeper, and very possible, justice and goodness — two concepts that are too often smothered in hypocrisy and what John Kenneth Galbraith called “the popular wisdom.” In other words, the accepted ignorance that passes for “common sense.”

So we would not accept the usual axioms that, “Nothing is going to change.” “Go with the flow.” “Things are the way they are, get used to it." We were not going to get used to it. We were going to change the flow; no matter how much effort it took to do so.

What Stonewall did, and what we did after, was to give queer people permission to release the innate, and, in the most profound sense, “decent” parts of themselves. This was a struggle, but we were not alone in it — because so many of us were fighting against real self-destruction — desperate for some act of liberating self-creation, that only together we could give each other.

We had our forefathers and foremothers working in the shadows, some of them sentenced to obscurity because they could not be recognized by society or academia for decades, even a century, to come. What we learned in the Gay Liberation Front, and many of the organizations that we enabled to come after us, is that along with liberation comes self-invention, but this does not come without responsibilities.

First of all, we have to see that we have a responsibility to each other. And part of that responsibility is to create a change in society’s attitudes that will allow us the safety to be ourselves, and — as we learned later when we marched and picketed for a Gay Rights Bill to be enacted in New York, decades before it finally happened — actual legality should follow this.

For years, our oppressors have said that either we were not worth the law, or that any change in the laws in our favor would mean the “end of civilization” or “morality,” or any of the other usual lies that they have used to destroy us. The old-school orthodox and fundamentalist religious groups have said that even approaching us honestly is simply too “sensitive” for open discussion.

So, they want to keep us a dirty secret that can only come out with the kind of scandals recently pummeling certain religious closets. What this has shown us is that the closet is an evil, festering place, and only tearing the doors out by their hinges will change that.

What the Stonewall Rebellion, the Gay Liberation Front, and many other LGBT groups have revealed is that there are no dirty secrets, only dirty minds. And what we have all done is clean away centuries of the filth and hypocrisy in the way.

This has altered life in America, and the world — LGBT liberation has become one of the world’s most universal movements. But we have also seen the reaction of fear and ignorance to it. The fear is always basically the same: that patriarchy in its rigidity holds the morals of the world together, and queer people threaten this rigidity. The rigidity is for some people “comfortable.” They find a refuge from their own problems in it. It’s like a shell guarding some alarmed, very scared creature within. They demand a respect for the shell — a respect for their own homophobia, and their resorting to violence in keeping queer people, women, and other oppressed groups in their place.

We understood this in the Gay Liberation Front; we also understood that it takes work even to grant people the security to leave their shells. This work has to be done by all of us. Sometimes it is overt political work, and other times it is simply the everyday work of investigating crimes against victims of sexual and gender violence, as well as changing the laws that allow the perpetrators of this violence to go not only unpunished but even lauded in some local or popular media.

The question again is, what did Stonewall do, and what does it mean to me? The answer is simple: everything and nothing. It gave much needed permission to those in desperate need of validity; but on its own, it did not really change the laws of American society, that dictated that “normal,” “family” heterosexual social and sexual mores comprised both the American state and a state religion in themselves.

Most thinking people have realized this was only a front, another shell. And they refused to give up the work needed to change it. So this work, in itself, actually changes the question. The real question is not what was the rebellion of Stonewall and what did it accomplish, but what can we do to foster its spirit and keep that “I’ve had enough!” moment going?

This means that the responsibility to see and change human attitudes and mores to include the excluded has got to go on. We were all there at Stonewall — and I very much feel that now, in this very trying and challenging time, the work of that pivotal moment has, finally, just begun.

Activist, poet, and author Perry Brass has published 19 books, was a member of the Gay Liberation Front and co-editor of Come Out!, the world’s first gay liberation newspaper, and co-founded the Gay Men’s Health Project Clinic, the first clinic for gay men on the East Coast, now operating as Callen-Lorde Community Health Services, and the Rainbow Book Fair, the largest LGBT book event in the U.S.

* This piece was adapted from a speech that given on May 1, 2019 as part of a panel at the American Bar Association’s LGBT+ Forum.