Yoko Ono's Debut in Cold War New York

By Brigid Cohen

Long overshadowed by her celebrity marriage to John Lennon, Yoko Ono has increasingly gained recognition for her wildly imaginative work as a multidisciplinary artist and intellectual. Nonetheless many people know nothing about her early career—a quintessentially New York story of immigration, haunting memory, and precarious new beginnings in cultural exchange. In following the threads of her story, we will see that it speaks not only to her own resilient creativity but also to larger dynamics of power that defined New York as a multiethnic capital of empire during the early Cold War.

The post-World War II arts boom transpired across a terrain of unequal power and citizenship. In the 1950s and 1960s, the city’s arts patronage and infrastructure flourished with support from soft power projects designed to promote US prestige at home and abroad. Public and private organizations sought to invest the city with an infrastructure befitting New York’s status as a symbol of American power. In this setting, minoritized and displaced creators such as Ono exemplified a dual dynamic. While they wielded power through their transnational contacts and helped spur innovation in local arts communities by nurturing connections between arts scenes and institutions across the world, they also remained subject to the vicissitudes of unequal citizenship and institutional gatekeeping in the US. This duality defines New York as an imperial metropolis – a hub for immigration and crossroads for cultural exchange, yet also a seat of power with discriminatory institutions and social codes that regulated diversity from within.

From the beginning, Ono lived a life between geographies and cultures. Born in Tokyo in 1933, she spent her childhood shuttling between Tokyo and San Francisco, following her father’s banking career. Ono’s mother’s family were merchant class founders of Japanese capitalism while her father descended from the hereditary military nobility. In keeping with this cosmopolitan background, Ono’s early education was devoted to Buddhist and Protestant theology, Japanese calligraphy and poetry, painting, German lieder singing, Italian opera, and Western classical piano.[1] This high-class, “feminine” education was consistent with the “good wife, wise mother” citizenship model, which enshrined patriarchal household structures and designated women’s duty as managing the household and children’s education.

Ono would soon rebel against these norms. She began to discover her intellectual and artistic vocation as a child fleeing the Tokyo fire bombings in 1945: “We had no food to eat, and my brother and I exchanged menus in the air. We needed new rituals in order to keep our sanity. We needed our powers of visualization to survive.”[2] After the fire bombings, she and her family endured starvation conditions in the countryside outside Nagano while her father was interned as a prisoner of war. “The sky was the only constant factor in my life,” she remembered, “which kept changing with the speed of light and lightning.”[3] From her perspective, there was no going back to the conventional life she had led. As she explained, “My strength at that time was to separate myself from the Japanese pseudosophisticated bourgeoisie. I didn’t want to be one of them. I was fiercely independent from an early age and created myself into an intellectual that gave me a separate position.”[4] As a first step in this direction, she entered Japan’s prestigious philosophy program at Gakushuin University in 1951 as its first female student. Ono immersed herself in the phenomenological tradition, studying such thinkers as Kierkegaard, Husserl, Heidegger, and the French existentialists. Her family disapproved. After two semesters, she withdrew from the program to study poetry and music at Sarah Lawrence College near her family’s new home in Scarsdale, New York. She finally dropped out of college in the mid-1950s to elope with the composer Toshi Ichiyanagi and embark on a career in the arts. At this point, her parents disowned her and she effectively entered a gendered exile from Japan.

After World War II, Ono tended to define herself as neither Japanese nor American, but rather as “an amalgam.”[5] The violence of Japanese militarized society and the U.S. bombings of Japan made it difficult for Ono to identify with either of the nations in which she had been raised.[6] Moreover, as Ono started her career in mid-century New York, her sense of belonging in either Japanese or US-based art scenes was tenuous. The “good wife, wise mother” citizenship model in Japan precluded women from establishing serious arts careers there. At the same time, Ono could not easily have embarked on a path toward US citizenship, because of the severe anti-Asian quota restrictions codified in the Immigration Act of 1924 and the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, which remained in force until 1965. Reinforcing this legal barrier to US belonging were myriad symbolic and cultural ones. Indeed, Ono enjoyed only a conditional welcome in New York’s avant-garde.

Ono made her debut in New York’s downtown scene during the heyday of composer John Cage’s guru-like presence there, when he popularized the study of Zen Buddhism in conversation with such figures as D.T. Suzuki. Cage famously sought to open up musical works to environmental sounds, to erase the traces of individual intention and ego from musical composition, and to integrate the use of chance methods (such as coin tosses) into musical composition toward that end. Cage’s Zen-inspired compositional practice exemplifies Cold War Orientalism, a term coined by Christina Klein to describe “the mid-century US fascination with Pacific Rim cultures” that attended and legitimated the expansion of US geopolitical power abroad. To be sure, Cage and his circle depended on new funding opportunities that arose in conjunction with Marshall Plan reconstruction projects in occupied West Germany and beyond, including the Darmstadt Summer Courses for New Music.[7]

While Ono developed a warm friendship with Cage after the German-Jewish refugee composer Stefan Wolpe introduced them, Cold War Orientalism was a condition of Ono’s entry into the downtown scene. It was also, unfortunately, a condition of her exclusion. Ono’s earliest performances took place in the Chambers Street Loft Series, which featured artists who had met in Cage’s composition class at the New School. For this performance series, Ono conceived the idea of renting the loft of a hundred-year-old Italianate commercial building in Tribeca and paid the $50.50 monthly rent. Ono co-organized the series with the composer La Monte Young. Nonetheless, her works did not appear formally on the series program. And Ono found herself denied credit for her role in organizing and producing the series, which Young claimed as solely his own in the series invitations, programs, and oral history. Instead, there circulated a sensational rumour that she was a “kept woman” housed in the loft by a “wealthy Chinese man”— a story that originated in some artists’ crude joke that Young’s name sounded Chinese.[8] Ono later attributed this unfair treatment to gender bias: “Most of my friends were all male and they tried to stop me being an artist.”[9] The very community consumed by a craze for Zen also found pleasure in the Orientalist image of Ono as Young’s concubine. Later in an interview, Ono reflected with ironic understatement, “They had to think about how to think about an oriental woman. I think it was very difficult for a lot of people who never had to deal with anybody oriental before.”[10]

The Loft Series featured artists who continued their activities from Cage’s class at the New School through a new sponsoring organization called the New York Audio Visual Group. As Dick Higgins, a key member of this group, recalled, the Loft Series provided a forum in which to witness the “results” of work they termed “research art,” which focused on the use of “systems, charts, randomizations” in the production of music and sound— a reference to the kinds of chance-derived and indeterminate scores Cage had taught.[11] The concerts were not public; rather, Ono and Young sent invitations only to a small circle of interested parties, labeled with the emphatic disclaimer “THE PURPOSE OF THIS SERIES IS NOT ENTERTAINMENT.” As Higgins recalled, Young and the series not only scorned entertainment but also “very much rejected the idea of dramatic or theatrical value.”[12] The composer Philip Corner – whose work Ono tried to have performed in her loft, before being thwarted by Young’s objections – observed how zealously Young policed the boundaries of his circle: “[It got back to me] that he considered me a reactionary because I still used crescendos.”[13]

Ono creatively responded to the challenge of her own noninclusion by staging dramatic guerilla performances. On one evening, for example, she could be found flinging her hair and throwing dried peas from a bag at visitors. By her account, this composition— which she called Pea Piece— transformed a ritual she remembered from her childhood, the rural spring custom of throwing soybeans to ward off oni, which in Japanese folklore resemble devils, demons, or trolls. The sounds of the scattered peas delighted Ono, which she heard, in the spirit of Cage, as a kind of music in itself.[14] But unlike Cage, Ono also deliberately staged Pea Piece as a dramatic gesture that transformed actions from personal childhood memory, translating them within a contemporary setting. In the context of the Loft Series, the downtown artists who excluded her from her own programs could themselves stand in as the devils she needed to ward off. It is also relevant that World War II-era Japanese children’s literature and films specifically depicted Western men as oni, foreign devils – a history that brings another layer of richness to Ono’s hybridizing translation of this ritual to catch American downtown artists off guard. Her gestures of hair flinging and pea throwing worked strategically to ensure that she would be remembered and talked about, despite being omitted from the official program of her own Loft Series. Needless to say, this performance contradicted Orientalist stereotypes of feminine submission.

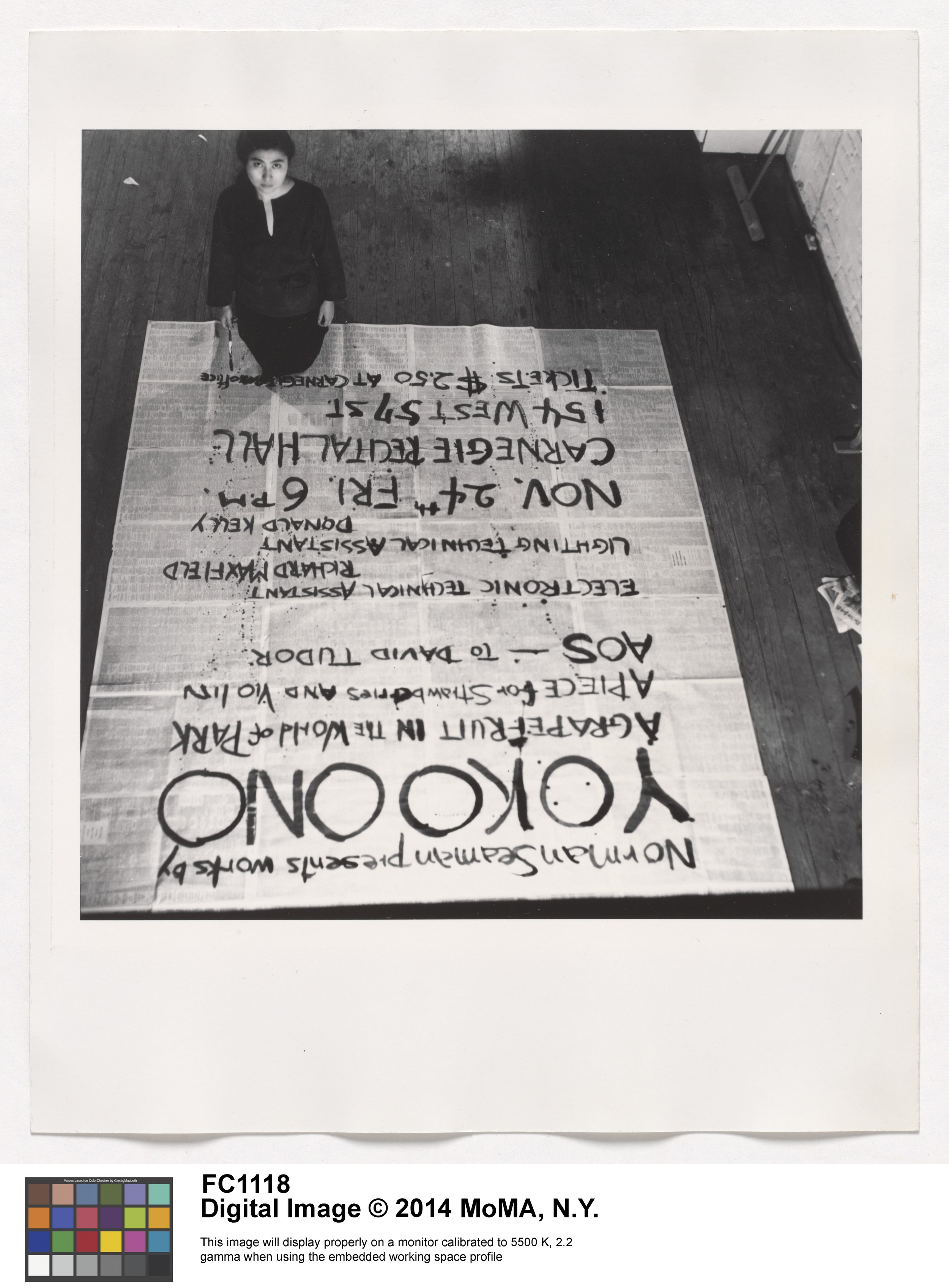

Ono’s flamboyant performance of Pea Piece agitated against the affective tone of placidity then in vogue in her circles. She did not conform to the expectations of Zen coopted by white American men in her milieu. Instead, Ono assumed a stance of dissatisfaction and insisted on the importance of personal memory, dramatic action, and storytelling. After the Loft Series, her first large-scale work AOS-to David Tudor was an “opera” about “the blue chaos of war” informed by her own history as an internal refugee following the Tokyo firebombings.[15] In five acts, AOS - to David Tudor involved the juxtaposition of animal sounds with human voices, a dehumanizing pile-up of human bodies, primal screaming, and amplified playback of World War II-era fascist speeches, including one of Hitler’s addresses at Nuremburg. Ono described works such as Pea Piece and AOS not as a form of personal expression but rather as a “wish” or “hope” that transforms in the hands and minds of others. This ethos would come to animate her famous peace activism throughout her life.

In the 1960s, Ono would move beyond New York City to premiere her work in Montreal (1961), Tokyo (1962-64), and London (1966-68). At same time, she worked diligently to promote the work of other downtown artists abroad. Most notably, she organized John Cage’s first tour of Japan in 1962, together with Ichiyanagi. A major sponsor of Cage’s tour was Sogetsu Arts Center, which counted with Darmstadt as an important node in the cultural infrastructure of US soft power abroad.

While Ono enjoyed success in promoting the work of her male colleagues, she found herself shut out of the US foundation-based patronage networks that formed an “umbilical cord of gold” for the Cold War US avant-garde (to use Clement Greenberg’s evocative phrase).[16] This exclusion replicates funding patterns in the arts boom of the 1960s more generally: major public and private foundations seldom if ever sponsored women and minoritized composers during these fat times of ample spending.[17] The New York art scene depended on patronage, and this patronage operated according to a gendered and racialized caste system.

In 1966, when Ono first met John Lennon in London, she was broke, stranded without money for a return ticket to New York, living on a cheap diet of oatmeal and veggies, tending to her young daughter, and nursing wounds from a series of painful grant rejections. It was under these conditions that Ono finally reached a breaking point with the coterie New York avantgarde, which had long embraced her supportive presence but not provided any material basis for a sustained career or greater public outreach. In Lennon, she found a creative partner for mass media activism, as exemplified in their Bed-ins for Peace (1969) and “Imagine” (1971). Informed by the intertwined histories of violence in both of the empires where she had been raised, and another that she now lived in, she would pursue the peace projects at the heart of her vocation on a much broader scale. And she would abide in that work seemingly invulnerable to the hysteria her presence as an Asian woman renegade in the mass media would provoke.

Today, critics and audiences appear increasingly to move beyond the misogynist, anti-Asian, Ono-hating stereotypes that flourished after her celebrity marriage. They embrace her for her work in her own right. Yet it is also important to recognize that even Ono’s earliest work—prior to her marriage to Lennon, prior to her vilification in the mass media—responded to the extreme challenge of working as a Japanese woman in New York as a capital of US empire. She has in effect reckoned with a double erasure—overshadowed not only by her celebrity marriage, but also hampered by the structural conditions of art and music scenes in the US, Japan, and beyond.

It is important to see this erasure not only for the sake of Ono but also for other women and minoritized creators who facilitated innovation and community but found little basis for material support or remembrance. Today’s relatively meager arts patronage in the US may seem transformed beyond recognition from the arts boom of the 1950s and 60s. Yet the arts infrastructure and canons that emerged during that period still provide a silent foundation for contemporary institutions and creativity in ways we do not fully understand. Therefore, we should gain critical perspective on the material conditions of power that gave rise to those canons and infrastructures, just as we should look toward the untold stories they hold.

Brigid Cohen is Associate Professor of Music at New York University and author of Stefan Wolpe and the Avant-Garde Diaspora (Cambridge University Press, 2012). This post is adapted from her most recent book, Musical Migration and Imperial New York: Early Cold War Scenes (University of Chicago Press, 2022).

[1] Alexandra Munroe, “Spirit of YES: The Art and Life of Yoko Ono,” in Y E S Yoko Ono, ed. Alexandra Munroe (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 14-15.

[2] Munroe, “Spirit of YES,” 13.

[3] Yoko Ono, https://twitter.com/yokoono/status/288465840175726593, accessed 24 July 2023.

[4] Munroe, “Spirit of YES,” 17.

[5] Tamara Levitz, “Yoko Ono and the Unfinished Music of ‘John & Yoko’: Imagining Gender and Racial Equality in the late 1960s,” in Impossible to Hold: Women and Culture in the 1960s, ed. Avital H. Bloch and Lauri Umansky (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 222.

[6] Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2005), 81.

[7] Amy Beal, New Music, New Allies: American Experimental Music in West Germany from the Zero Hour to Reunification (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2006).

[8] Jonathan Cott, “Yoko Ono and Her Sixteen-Track Voice,” Rolling Stone, March 18, 1971, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/yoko-ono-and-her-sixteen-track-voice-237782/, accessed 24 July 2023. See also Edward M. Gomez, “Music of the Mind from the Voice of Raw Soul” in Munroe, Y E S Yoko Ono, 233, 237.

[9] Yoshimoto, 86.

[10] Yoko Ono, interview with Miya Masaoka, “Unfinished Music: An Interview with Yoko Ono,” San Francisco Bay Guardian (August 27, 1997), http://miyamasaoka.com/writings-by-miya-masaoka/1997/unfinished-music/, accessed 24 July 2023.

[11] Owen Smith, “Proto-Fluxus in the United States, 1959–1961: The Establishment of a Like-Minded Community of Artists,” Visible Language 26, nos. 1–2 (1992): 49.

[12] Smith, 49.

[13] Philip Corner, correspondence with the author, August 11, 2016.

[14] Yoshimoto, 86.

[15] Alexandra Munroe, “Spirit of YES: The Art and Life of Yoko Ono,” in Y E S Yoko Ono, ed. Alexandra Munroe (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 23.

[16] Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review 6 (fall 1939): 38.

[17] Michael Sy Uy, Ask the Experts: How Ford, Rockefeller, and the NEA Changed American Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020).