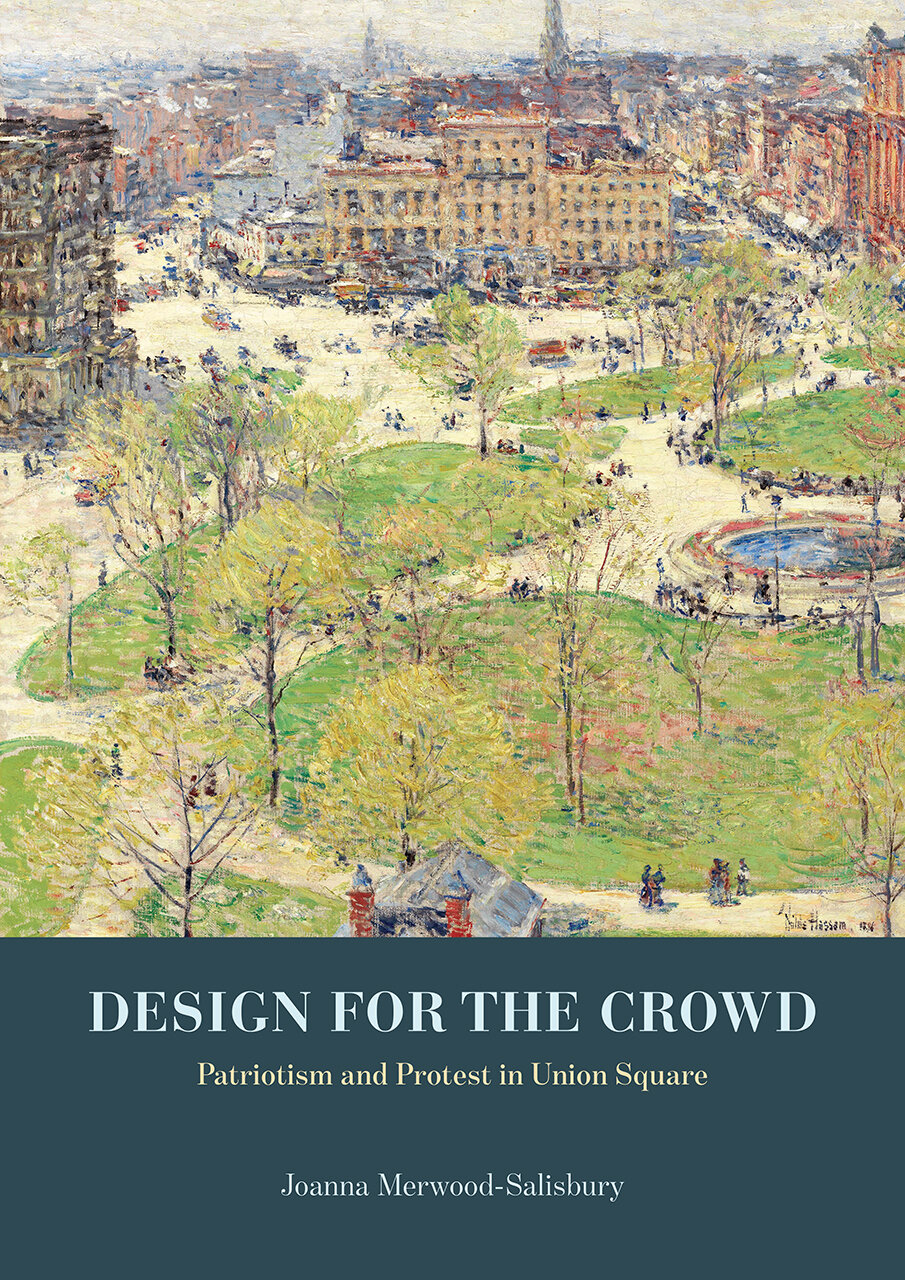

Design for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square

Reviewed by Donald Mitchell

Design for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square

By Joanna Merwood-Salisbury

University of Chicago Press

312 Pages

Almost immediately after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, crowds started gathering in Union Square, the closest big public space to Lower Manhattan’s “exclusion zone.” People brought candles and photographs, flowers and flags. They came to mourn and to commune, turning the square into “a shrine and memorial, layered with photos, handwritten messages, schoolchildren’s drawing, expressions of sympathy and sorrow from flight attendants who had been spared the luck of the draw,” as Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin later wrote.[1] Quiet and dedicated mostly to mourning in the first days, Union Square soon also became a place of debate and discussion: what should America’s response be to the attacks? Why invade Afghanistan? How to understand America’s geopolitical role in the world? A spontaneous social geography arose. Homeless people and street kids, many now unable to gather or stay in their usual places farther south, moved into the center of the park. Activists and street musicians colonized the southern steps, Christians the eastern side. A Christmas tree attached to a tall pole was erected by a couple of Ukrainian immigrants and became a gathering point. A church from Queens took over some flower beds and made a giant image of the now-destroyed World Trade Center towers out of flowers from a canceled garden show. Patriots paraded around the Square’s perimeter with American flags. The giant statue of George Washington on his horse was soon bedecked with flowers, a large American flag tied to the steed’s hooves and a just as big homemade peace symbol flag held high aloft on a pole by the President himself. A giant scroll of butcher paper was unfurled along a low fence by some art students and soon was filled “with radically contradictory messages and meditations,” as Marshall Berman described it, while also suggesting that what had been a rather sterile and somewhat lifeless park after a 1984 redevelopment overseen by the Union Square Partnership had overnight “become the city’s most exciting public space: a small-town Fourth of July party combined with a 1970s be-in.”[2] The New York Times concurred. By the first weekend after the attacks, “the park had become an impromptu outdoor festival,” the Times architecture critical Michael Kimmelman wrote. In the wake of the attacks, Union Square worked “as urban designs are conceived to do: bring strangers together on common ground, people who otherwise not have met, people who would not have bothered to notice one another on the subway or street.”[3]

Joanna Merwood-Salisbury opens and closes her compelling new history of Union Square with brief discussions of this moment in the Square’s history, writing that Union Square “served as a counterexample” to the “symbol of Western global dominance” — the Twin Towers — that were so violently destroyed on 9/11. Union Square became “a place of openness and inclusion, rather than privilege and exclusion” and thereby “affirmed the importance of urban public space in an age where much political discussion and protest had moved into the ephemeral space of the media.” Citing Setha Low, Merwood-Salisbury argues that Union Square in that moment stood as “an essential referent, countering… the new defensiveness in the post-9/11 era, a tendency to barricade and guard the common spaces of the city, in doing so denying the civil and political freedoms they represent.”[4]

But Merwood-Salisbury says nothing about what happened next. Early in the morning of Thursday, September 20 — the day before a big peace rally was scheduled to begin in the Square before marching north to the armed forces recruiting center in Times Square — police and work crews arrived at Union Square, pushed the homeless people out, fenced off the central part, and began dismantling the “missing” posters, photographs, paintings and banners that festooned the rails and benches, power-washing George Washington and his horse, throwing away candles, and scrubbing wax off the pavements. Built up over nine days in the wake of the attacks, New York’s “most exciting public space” was stripped clean in a matter of hours and essentially made off-limits for political debate and protest — and in its central parts, off-limits altogether. The Giuliani administration offered a number of shifting rationales for its action, ranging from an impending rainstorm (from which these people’s memorials had to be preserved) to the threat to health and safety the homeless encampment presented. But what seemed really to be at the root of the city’s action was precisely the democratic fact of the Square, its existence as a burgeoning, democratic public space with a logic all its own, increasingly governed (if not smoothly) by rapidly developing norms and customs, by the ingeniousness of its spontaneous social geography. Above all the Giuliani administration felt compelled to restore order to the Square, to bring it back under the control of the authorities, not let it remain governed by the contentious wills of the people, especially as the U.S. was preparing for war — a time when a stiffened patriotism, not a messy democracy was called for.[5]

It is curious that Merwood- Salisbury does not discuss this second act in Union Square’s post-9/11 drama for it is every bit as important to the story she tells in Design for the Crowd as the first act. Merwood-Salisbury’s central argument is precisely that the biography of Union Square can only be understood as a never-ending contest between two ideals of — and practices in — Union Square and public space more generally: on the one hand an ideal of the Square as an orderly, open space, within which leisure and patriotic spectacle dominate, while the values of property and propriety are upheld; and on the other hand the Square as a space of democratic, maybe even agonistic gathering and mass protest that often seeks to contest that order. When the Giuliani administration reclaimed Union Square on September 20, 2001, it sought to reclaim it in the tradition of that first vision from what had become, perhaps, the best example yet of the second.

One of the great merits of Design for the Crowd is that while its analysis is rooted in exploring the shifting terrain of this dynamic between order and agonism, patriotism and protest, it also is closely attentive to those moments when the distinction between the ideals is not just blurred, but actively remade. As Merwood-Salisbury makes so clear throughout the book, it just will not do to root our understandings of, and struggles for, public space in the city (and Union Square in particular) in some sort of nostalgia for a space that never was: a somehow purely open and inclusive, democratic and “authentic” public space. Rather we need to understand “the history of the Square as both real public space and the symbol of competing ideas about the operation of democracy in the United States.” By “real” she means as it material is and has come to be: through design, through law, through use, through policing, through the fighting out of these “competing ideas.”

Part architectural history, part social history, and part a history of New York City in all its ethnic, racial, class, and political complexity, Design for the Crowd begins by showing how Union Square was birthed by some the geographic quirks that arose when the 1811 grid was overlaid on the existing routes (and ownership structure) of pre-industrial New York, combined with the entrepreneurial vision (and power) of the lawyer and property speculator Samuel Ruggles. With the city growing north, and water from the Catskills now being pumped south, Ruggles saw a chance to make a killing and began amassing property (mostly through leases) between Fourteenth and Twenty-Third streets, and understood well (in part from his earlier experience with the private Gramercy Park) that a park at the confluence of the Bowery and Broadway would do wonders for the value of the properties that he held. A keen judge of shifting political economies, Ruggles figured that the park would be even more effective if it were owned and developed by the city (while effectively being controlled by a small elite), convincing the Common Council that the rising property values nearby would mean a boon in tax revenues. As Merwood-Salisbury shows, then, however we understand Union Square, it began life in the grubby precincts of real estate.

Many of us (myself included) argue that when the primary purpose of public space is to support the accumulation of capital in the urban built environment (when parks are primarily real estate) something crucial — like the democratic potential of public space — is lost, or at least seriously threatened. But if that is the case, Merwood-Salisbury seems to suggest, it is only because something crucial — like the democratic potential of public space — has at times been won: public spaces have at times been wrested out of the clutches of capital, however temporarily. Democratic public space is not born: it is taken and made.

Over the course of its now-almost-two-century existence, Union Square has been shaped by the contest between those who want to take it and make it agonistic, and those who want to hold it and assure its value as real estate. This book makes clear that park design played a central role. Merwood-Salisbury does an excellent job of tracing out how the different design ideas, and the eventual designs that were realized, shaped the kinds of crowds Union Square attracted and hosted. The book is meticulous in its discussion of not only the specificities of both the original design of the Square and its subsequent many redesigns, but also how such designs fit into — or pushed against — contemporary design orthodoxies, elite notions of how patriotic democracy should be expressed in public space, and the political and economic realities of the city. Union Square was a showplace, designed not only to enhance real estate values, but also as a place where the public could be called to order and asked to witness the spectacle of America: Fourth of July celebrations, massive military send-offs, and Centennial celebrations. Soon after its construction, Union Square became the place in New York where America showed itself to itself.

But Merwood-Salisbury also shows how as soon as the park was built, and through each of its successive redesigns, people have also always used it otherwise — in ways not quite intended, for either (sometimes elicit) social purposes or for (sometimes explicit) political purposes. As bushes grew, couples climbed under them for a bit of privacy. When depressions hit (and even when they didn’t), homeless people slept on the Square’s benches, lawns (when they existed), and flat spaces. And when Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvin Vaux redesigned the Square to feature a large open plaza at its northern end for mass meetings, unions and radicals of all sorts arrived by their thousands, perhaps to the satisfaction of Olmsted and Vaux (who, Merwood-Salisbury shows, had a more capacious and open respect for mass democracy than they are usually allowed), but frequently to the annoyance — and sometimes fear — of the authorities. The history of Union Square is thus also a history of policing: policing deviance and policing protest. During depressions cops were charged with “rous[ing] sleeping tramps by slapping them on the soles of their feet with a sturdy nightstick” or, when they grew too many, rounding them up, charging them with vagrancy and “sentenc[ing] them to a term at the workhouse on Blackwell Island in the middle of the East River. This draconian practice was justified as a valid effort to reduce crime.”

Design for the Public is, in other words, a history of continuity: the role, and sometimes even the means, of the cops, have little changed in the ensuing years. But the book is also a history of change, the history of a changing city. Merwood-Salisbury does a fine job of tracing how the precincts around Union Square shifted economically, from elite residential area to industrial hearth, from a magnet for at first exclusive and then bargain shopping, from a depressed and disinvested district to a gentrified center of New York’s new food culture, and how such shifts reworked both its use and the place of the park in the popular imagination. As industry grew, Union Square famously hosted the world’s first massive Labor Day parade, and the Square quickly became the central gathering point for labor activists and radicals of all stripes. Merwood-Salisbury lays out in fine detail how the park became, at least until World War II the central gathering place for labor and progressive causes, with May Day assuming at times a presence almost as big as Labor Day. And she shows how such displays of radical power were often met not only with restrictive laws seeking to silence dissent but especially by the impressive violence of the police.

Yet sometimes this is also where Merwood-Salisbury’s narrative gets away from her. On the one hand the scope and extent of, for example, Communist organizing during the first half of the Depression, within which Union Square protests played a central role, is underplayed. On the other hand, the violence (often by the police) that attended Communist mass meetings is overplayed. At various places in the book, Merwood-Salisbury describes the exceptional violence of the 1863 Draft Riots, which lasted for days, and the stunningly large number of people killed in the Orange Riots of 1871, she notes the violent police riot at Tompkins Square Park in 1874 and the use of militias during the several days of rioting around Astor Place in 1849 (the so-called Shakespeare Riots), and she could easily have supplemented these with mention of the deadly, several day-long Tenderloin Riots in 1900 or the hours-long “Police Pogrom” on the Lower East Side in 1902. It comes as a bit of a shock, therefore, to see Merwood-Salisbury describing the police assault on a Communist-organized protest of the unemployed in 1930 — that “lasted no more than fifteen minutes” and in which no one was killed (though fifty were injured) — as “initiating one of the worst riots in this history of the city.” It was violent, and it was an unwarranted attack by the police. It was also highly indicative of the struggle between patriotism and protest in Union Square. But it was not even close to being “one of the worst riots” in the city.

What it was, however (and this is why it matters), was the beginning of yet another attempt by the forces of urban order to reclaim Union Square. By the time the U.S. entered World War II, this reclamation was just about complete, as Merwood-Salisbury shows. Demonstrations were repressed, and soon enough the big plaza Olmstead and Vaux had designed for political gathering was turned into a parking lot (and eventually an impoundment area for cars seized by the police). The police impoundment was in many ways symbolic of the Square’s — and the surrounding district’s — decline, which was concomitant with a concerted effort by area merchants and city officials to stamp out all vestiges of May Day and other symbols of radicalism and to replace them, during the Cold War, with choreographed spectacles of “Loyalty,” all this at a time, Merwood-Salisbury avers, when protest as an emplaced, embodied activity — and show of force — was being replaced more and more by broadcast images, when the role of material public space was being replaced by the media, and Union Square’s longstanding as a place for protest was on the wane.

I am not convinced by this argument. Design for the Public makes it clear that other factors, such as the redesign of the Square that Marshal Berman bemoaned and the heavy legal restrictions on protest that are here so well documented better account for Union Square’s decline as a political place from the 1960s through the 1990s. Moreover, any number of resurgences of protest, uprising, and riots in New York and around the world in the years since the advent of TV and then the computer and mobile phone, makes the loss of public space to the cyberworld a difficult case to make empirically. Even in Union Square: well after the TV and the Internet, the Square continually threatens to become a vibrant agonistic public space, whatever the designs for it to be otherwise might be. The Occupy movement made Union Square an important northerly outpost; May Day has returned; and there were those nine impromptu days in September 2001 when Union Square became “a giant outdoor festival.” In Merwood-Salisbury’s own words, these latter-day moments raise the question: “at what point do definitions of what is truly public expand and break”? The whole history of Union Square, Design for the Public so clearly shows, is at once the spatial asking of, and a contentious, on-going spatial answer to, just that question. “The Square,” Merwood-Salisbury writes by way of conclusion, is not just a stage for public life, but a site on which ideas of publicness are imprinted and tested.” Act 2 of the public remaking of Union Square in the wake of 9/11 — the Giuliani Administration’s reclaiming and closing of the Square in the name of order on Day 10 — was hardly the final word. But it was an important one: one that proved the very thesis of this book.

Donald Mitchell is Distinguished Professor of Social and Economic Geography at Uppsala University.

[1] Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, “Introduction” in Sorkin and Zukin, eds., After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City (New York: Routledge, 2002), viii.

[2] Marshall Berman, “When Bad Things Happen to Good People,” in Sorkin and Zukin, After the World Trade Center, 11.

[3] Michael Kimmelman, “In the Square, a Sense of Unity: a Homegrown Memorial Brings Strangers Together,” New York Times, September 19, 2001.

[4] See Setha Low, “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza,” in Sorkin and Zukin, After the World Trade Center, 163-71.

[5] My discussion of the Square and its fate in 9/11 draws on my (unsigned) chapter, “Union Square: After September 11, 2001,” in Neil Smith and Don Mitchell, eds., Revolting New York: How 400 Years of Riot, Rebellion, Uprising, and Revolution Shaped a City (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018), 258-60.