“this city gets in one’s blood stream with the invisibility of a lover”: City-Making as Queer Resistance in New York, 1950-2020

By Davy Knittle

At the October 1979 Second Sex Conference at New York University, Audre Lorde famously argued, “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” [1] In her use of the phrase “the master’s house,” Lorde suggests that the tools that create inequality cannot be repurposed to make counterhegemonic activism and scholarship effective. This suggestion is so central to academic conversations about race, gender, and sexuality that Lorde’s intervention has become canonical to work that addresses how social and political power and resistance take shape. In the voluminous reception of Lorde’s remarks, however, the role of the master’s tools in dismantling housing is most often read as metaphorical. [2] In a few instances, dismantling housing is read as having architectural resonance, as part of a use of “metaphors of built space” to describe “race, sex, gender and, by extension, class.” [3] But Lorde’s contemporaneous critiques of how urban redevelopment in New York exacerbated racialized social inequality suggest, alternatively, that the tools and house are not only metaphors. They are instead informed by her awareness of the built environment and the planning and policy approaches that transformed New York City in the wake of urban renewal and shaped who had the chance to live in the city with minimal risk of violence, harm, or displacement.

Despite the importance of urban systems to how Lorde characterizes power and inequality, she is not thought of as an urbanist writer. But what becomes possible when we think of Lorde as such is a new approach to telling the familiar history of spatial and political change after urban renewal. As with many queer and trans writers active from the early moments of urban renewal to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Lorde uses city-making tools to provide new ways of relating to the city. Importantly, these queer and trans urbanist writers—from the New York School poet James Schuyler to the contemporary trans novelist Zeyn Joukhadar—propose uses, designs, plans, and policies for urban spaces and environments that are focused on facilitating the survival of marginalized people. These queer and trans writers draw attention to cisheteronormativity as a relationship to the built environment as well as to desire, kinship, and identification. Their work makes evident how, after urban renewal, a cultural imaginary of the single-family home came to define heteronormativity as a relationship to housing as well as to race, gender, and sexuality. It becomes necessary, then, to account for how built environments and normative ideas of race, gender, and sexuality in the U.S. have been co-constituted since the end of World War II in order to more fully tell both queer and trans history and the history of urban redevelopment in New York City.

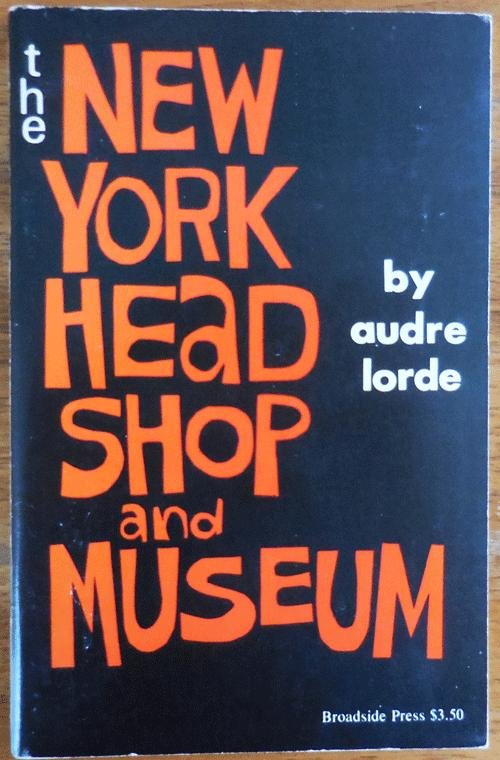

Audre Lorde, The New York Head Shop and Museum. Broadside Press, 1974.

A focus on queer and trans relationships to city-making in New York offers another way of doing queer and trans history in the city. For urban and planning historians who do not work on queer and trans topics, it also offers different approaches to the history of urban renewal and its aftermath. Looking for city-making tools in the work of queer and trans writers reveals an archive of urbanists attentive to how changes in the built environment affect their survival. Lorde, for instance, was aware of the dramatic redevelopment happening around her in New York, which built upon her careful observation of the city for many decades. She graduated from Hunter College in 1959 and then worked as a social investigator with the Bureau of Child Welfare. [4] Many of Lorde’s poems in her 1974 collection New York Head Shop and Museum speculate about the city’s future as New York neared fiscal crisis in the mid-1970s. [5] In the poems, Lorde is especially focused on people and urban spaces controlled by insufficient housing. In “Hard Love Rock #11,” she describes her skepticism about New York’s privileging of real estate development that only produced “sacked cities not rebuilt / by slogans.” [6] In “New York City 1970,” Lorde writes, “I am bound like an old lover—a true believer— / to this city’s death by accretion and slow ritual.” [7] Lorde depicts her relationship to the disinvested city as a form of kinship. Her life is entangled with the city’s life, such that its “death by accretion” weakens her own life chances.

In her other work in the 1970s, Lorde often used infrastructural examples to explain social and affective relations. In a 1975 interview, when she was asked a question about why she was not concerned about whether there are Black astronauts or Black presidents, Lorde explains:

The whole concept of presidencies, of spending millions and millions of dollars in getting people to that satellite up there when we can’t even move them through Detroit, or through New York without, you know, killing people. Two hundred and fifty people were killed in the New York subways in the last three months and that is a fact: pushed, jumped, or fallen. [8]

Lorde’s thinking about how infrastructure shapes life chances conditioned both how she read the city and how she read her own intimate relationships with the built environment. In another interview a year later, she describes accidentally breaking a window of her “very old Victorian house on Staten Island.” When she unlocked the window, “somehow the chain broke and the window fell down immediately and caught my hand.” Lorde learns from the pain of the window crushing her hand that because she could not remove her hand until someone came to help her, “the pain is transformed. The intensity changes.” She goes on to note that “that is just as true about emotional pain: it will change or stop.” [9] Here, Lorde relates an experience with old housing infrastructure to her affective life. It is important to her description that a real window fell on her hand. It is also useful for her thinking about an abstract concept, but what it provides is a tool and not only a metaphor.

Nearly fifteen years before Lorde’s comments at the Second Sex Conference, the Black feminist poet and writer June Jordan similarly linked urban spatial transformation to the use of norms of race and gender to control marginalized people in her 1965 project “Skyrise for Harlem.” Where Lorde referenced the harm caused by inequitable city making projects, Jordan proposed using new approaches to city-making as a necessary tool for racial and gender justice. For both authors, city-making includes the informal use of formal planning and policy strategies, but also other modes of speculating about new ways of organizing social, spatial, and environmental relationships in the city, often aslant to its official design. In opposition to the kinds of spatial transformation enacted by renewal projects, Jordan described “Skyrise for Harlem” as “a proposal to rescue a quarter million lives by completely transforming their environment.” [10]

Both Lorde and Jordan detail the intimate relationship between urban residents and the built environment. In her urbanist writing, Jordan additionally connects the city’s built environment to its ecological context. When Lorde writes that she relates to the city like an old lover, or when the writer, artist, and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz writes of New York that “this city gets in one’s blood stream with the invisibility of a lover,” they express a queer intimacy with the city that encourages them to invent ways to survive in spaces designed to deprioritize their existence. [11] Their work demonstrates how imagining new versions of New York or using infrastructure in ways that exceed its initial planning is constitutive of everyday life for marginalized urban residents.

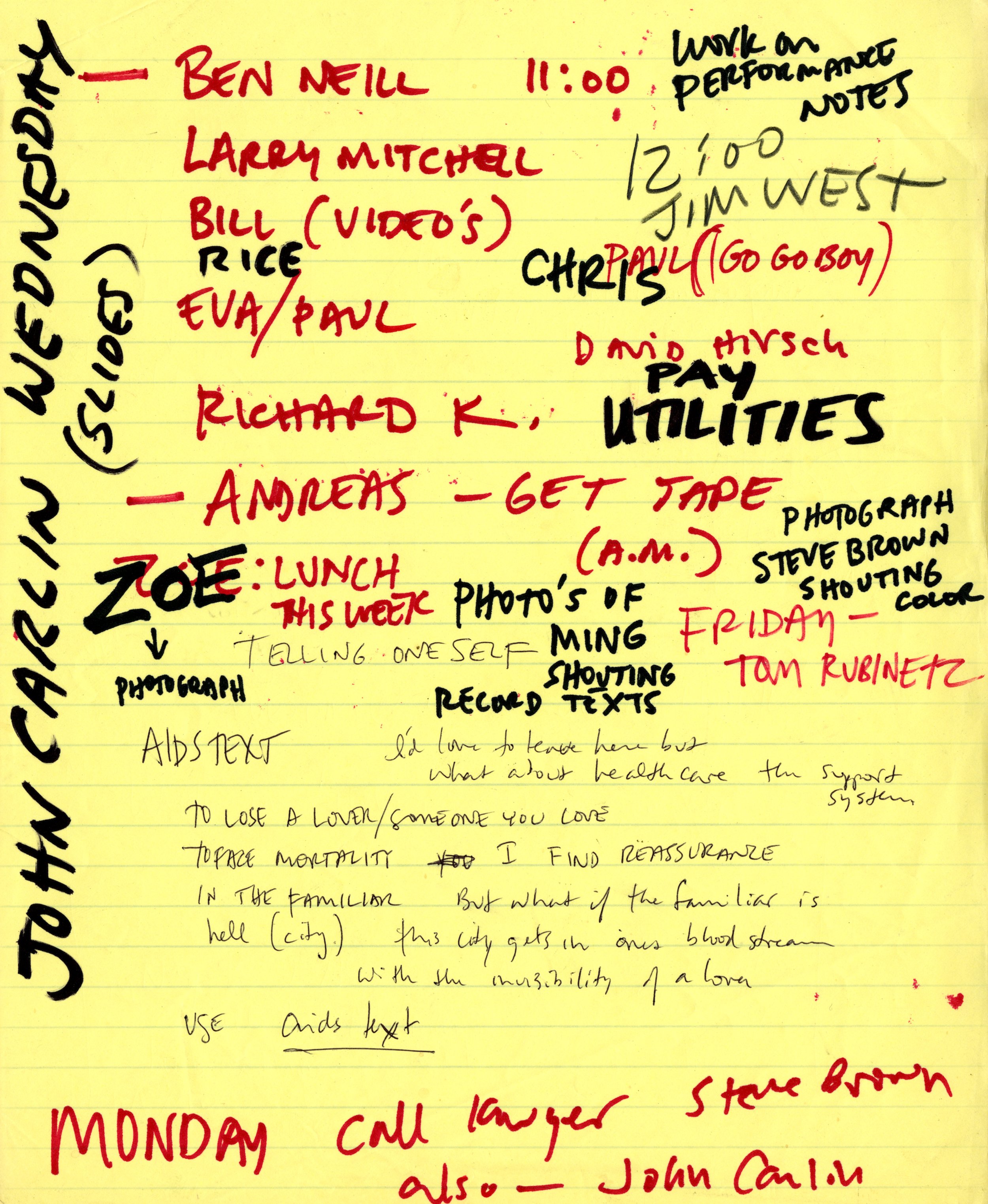

Phone Log, Undated; David Wojnarowicz Papers; MSS 092; Box 7, Folder 19; Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University Libraries. Copyright Estate of David Wojnarowicz; Courtesy of the Estate of David Wojnarowicz.

Both Jordan and Lorde turned to the transformation of urban space in New York in the wake of the urban renewal demolition and clearance projects of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s to illustrate how race, gender, and sexuality were co-constituted with the transformation of the built environment. Queer and trans studies scholarship that extends from their work includes a focus on queer and trans people but also on the structures of power that political scientist Cathy Cohen suggests when she asks, “How do we use the relative degrees of ostracization all sexual/cultural ‘deviants’ experience to build a basis of unity for broader coalition and movement work?” [13] Cohen, and nearly three decades of scholarship that follows her transformative contributions to queer studies in the late 1990s, advocates for situating queer and trans methods as tools for explaining how expectations of normative race, sexuality, and gender unevenly affect people of all genders and sexualities.

And yet, while work in queer and trans studies has engaged extensively with queer and trans social, cultural, and political life in New York and many other cities, this work often does not attend to how the transformation of urban space and ecology in the decades after World War II contributed to the production of a normative conception of race, gender, and sexuality. Meanwhile, studies of queer life in New York have largely focused on fixed spaces populated by gay, lesbian, queer, and trans-identified people: clubs, bars, cruising areas, and hubs for organizing and activism. As geographer Jack Jen Gieseking notes, however, “Dominant narratives of lgbtq spaces often highlight activisms, leaving out everyday experience.” [14] Queer and trans studies looks not only to the social and political life of queer and trans-identified people but also to systems of power that produce dominance by distributing resources in ways that both follow and produce expectations of normative race, gender, and sexuality. But queer urban historical scholarship has focused much more on the former project than it has on the latter. Lorde and Jordan’s use of city making strategies reveals how queer everyday experience is lived in intimate relation to urban infrastructure as well as to queer-identified spaces.

While an attention to city-making tools has remained a constant in queer and trans cultural production since the beginning of urban renewal, changes to queer, trans, urban, and environmental frameworks have transformed the shape of city making in queer and trans thought. In the 1950s and 1960s, mass clearance, demolition, and suburbanization shaped the conditions in which early conversations that informed both gay liberation and queer, trans, and feminist activism took place. In the late 1980s and 1990s, activism around early public conversations about climate change and the rise of gentrification in New York were entangled with organizing in the early era of HIV/AIDS. Urbanist queer and trans writing about New York in the past 20 years has focused increasingly on combatting gentrification, exposing environmental racism, and forging multispecies relationships that demonstrate the scope of harm caused by predatory urban change.

Party Wall Chimney: Site 21 at 92nd Street and Columbus Avenue. Photograph by Seymour Zee. Department of Housing Preservation and Development Photograph Collection, 1969. New York City Municipal Archives. Courtesy of New York City Municipal Archives.

These queer and trans approaches to city-making are motivated by what I refer to as “urbanist desire,” desire for, in, and with the city as at once a built environment and an entity that exceeds the combination of its buildings, ecology, policy, and population. Urbanist desire can take the form of using city-making tools, including policy and planning, to imagine new ways to facilitate survival; Or it can inform the writing of alternate urban futures designed for queer and trans persistence and made up of small spatial and environmental changes and unanticipated uses of urban space. Engagements with urbanist desire often draw attention to how people, infrastructure, animals, plants, and weather exceed the behavior anticipated by predatory urban planning and policy. Following how the design and dominant use of the built environment across these many moments in New York City’s history produce expectations of gender and sexuality, and how queer and trans writers use alternative tools to resist these expectations, gives urban historians new ways to trace how prevailing ideas of urban space and norms of race, gender, and sexuality have informed one another.

Davy Knittle (he/they) is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Delaware. His current book project, "Urbanist Desire and the Ecology of Queer and Trans Survival," describes how urban and environmental change shaped queer and trans cultural production in New York from 1950 to 2020.

[1] Audre Lorde, “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in This Bridge Called My Back, Fourth Edition, ed. Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2015 [1981]), 95, emphasis in original.

[2] For instance, in her feminist reading of the commons, Silvia Federici uses Lorde’s argument to explain that “the spirit of the commons resonates with Audre Lorde’s insight that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.’” Re-Enchanting the World: Feminism and the Politics of the Commons. (Oakland, PM Press), 2019, 168. In her discussion of the categories of power and difference, Ruth Wilson Gilmore argues that “One works with what is at hand; the problem is not the ‘master’s tools’ (Lorde 1984, 110) as objects, but the effective control of those ‘tools’ (Gilmore 1993). Ruth Wilson Gilmore. “Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography,” The Professional Geographer, 54, no. 1, (2002), 22. Susan Peck MacDonald, “The Erasure of Language,” College Composition and Communication 58, no. 4 (2007): 619.

[3] Jack Halberstam, “Unbuilding Gender: Trans* Anarchitectures In and Beyond the Work of Gordon Matta-Clark.” Places Journal. October 2018, https://placesjournal.org/article/unbuilding-gender/.

[4] Conversations with Audre Lorde xx

[5] In 1975, the city asked the Ford administration for financial assistance as it struggled to avoid bankruptcy, to which Ford responded by indicating that New York should, as the New York Daily News put it, “drop dead.” (Frank Van Riper, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” New York: New York Daily News, October 30th, 1975, A1.) As Kim Phillips-Fein argues, “The fiscal crisis that nearly sent New York City into bankruptcy in 1975 continues to reverberate in the city's dominant mythology.” (Kim Phillips-Fein. “The Politics of Austerity: The Moral Economy in 1970s New York" in Neoliberal Cities: The Remaking of Postwar Urban America, edited by Andrew J. Diamond and Thomas J. Sugrue, New York: NYU Press, 2020, 78.)

[6] Audre Lorde, New York Head Shop and Museum, (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1974), 24.

[7] Lorde, 6. Audre Lorde, “Interview with Audre Lorde, 1975,” By Margaret Kaminski, Conversations with Audre Lorde, Joan Wylie Hall, Ed. (Jackson, M.S., University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 8.

[8] Margaret Kaminski, “Interview with Audre Lorde” Conversations 8 Margaret Kaminski.

[9] Audre Lorde, “Interview with Audre Lorde, 1976” By Nina Winter, Conversations with Audre Lorde, Joan Wylie Hall, Ed. (Jackson, M.S., University Press of Mississippi, 2004), 16.

[10] June Meyer (Jordan), “Instant Slum Clearance,” Esquire April 1965, 109.

[12] Phone Log, Undated; David Wojnarowicz Papers; MSS 092; Box 7, Folder 19; Fales Library and Special Collections, New York University Libraries.

[13] Cathy. J. Cohen, “Punks, Bulldaggers, and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” GLQ, Vol. 3. 453.

[14] Jack Jen Gieseking, A Queer New York: Geographies of Lesbians, Dykes, and Queers (New York, N.Y.: NYU Press, 2020), xx.