Review: David Paul Kuhn's The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution

Reviewed by Steven H. Jaffe

If you open the New York Times’s “Extremely Detailed Map of the 2020 Election” online and move your cursor over New York City, you will hover above a blue sea dotted by islands of pink and red. The blue, of course, represents electoral precincts won by Joe Biden — the great majority of votes cast. The pink and red islands are those clusters of precincts where Donald Trump edged out (or in many cases blew out) Biden.

These islands proclaim a social and political geography that has been decades in the making. They include heavily Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods across central and north Brooklyn and central Queens, districts with their own distinctive legacies of conservatism. But they also include most of Staten Island and areas like Dyker Heights, western Bay Ridge, Gerritsen Beach, Whitestone, Middle Village, and Howard Beach, all outer-borough districts largely inhabited by middle-class and working-class white Catholics and some white Protestants. Many of these voters are the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Irish, Italian, German, and other New Yorkers who elected and reelected Franklin Roosevelt to the presidency, in the process helping to reinvent the Democratic Party as the bastion of a new liberalism that prevailed in local and national politics for half a century.

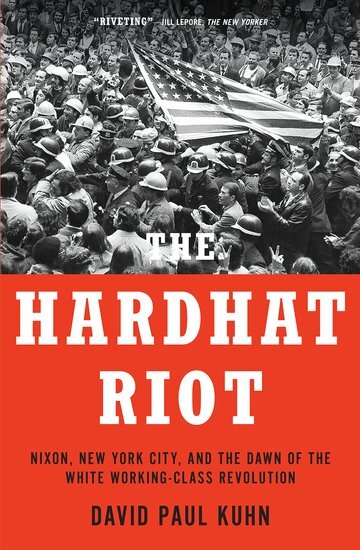

The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution

By David Paul Kuhn

Oxford University Press, 2020

416 pages

David Paul Kuhn’s The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution focuses on May 8, 1970, a symbolic date in the exodus of such voters from the “New Deal Coalition.” On that day hundreds of blue-collar workers — many of them construction workers building the World Trade Center — converged in the streets of lower Manhattan, chanting “U—S—A. All the Way!” as they physically attacked students protesting the Vietnam War. The “hardhats” also demanded that an American flag atop City Hall — lowered to half-mast by order of Mayor John Lindsay in mourning for four antiwar demonstrators killed at Kent State University in Ohio — be raised to full height. Over one hundred students, bystanders, and others were injured in the melee on the streets.

The day’s enduring significance was its marking of a new political reality, one in which white urban workers — once a crucial electoral base for the Democrats and for FDR’s New York-style big-government liberalism — redefined themselves as part of Richard Nixon’s conservative “Silent Majority.” Kuhn’s work is not merely an account of the riot itself, which in fact doesn’t erupt until the book’s thirteenth chapter. For Kuhn, May 8, 1970 is the culmination of accumulating tensions and a crucial prelude to the nationwide political shift that followed it, contributing to the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency a decade later. And, of course, these so-called “Reagan Democrats” and their kids — working-class and lower middle-class whites who shifted their allegiance to the GOP or became independents or ticket-splitters leery of Democratic liberalism — played a major role nationally in the elevation of Donald Trump to the White House in 2016. To be sure, the truly seismic shift was that of previously Democratic whites in the South and other parts of the Sunbelt into the GOP, remaking the nation’s electoral map between the mid-1960s and the 1990s. Yet by exploding in the country’s acknowledged urban bastion of liberalism, “Bloody Friday” gained an emblematic importance surpassing its direct impact on election outcomes.

The lasting value of The Hardhat Riot will be in Kuhn’s meticulous reconstruction of the events of that spring Friday in lower Manhattan. His multi-chapter rendering of the riot is a tour de force of research and historical narration. Having interviewed surviving participants and witnesses and pored over a daunting mass of sources including previously-unexamined NYPD files, Kuhn offers a taut account admirable in its commitment to recovering as accurately as possible the events unfolding in the financial district’s canyons that day: the march by antiwar student protesters to the steps of Federal Hall facing the New York Stock Exchange across Wall Street, the arrival of flag-waving workmen to confront them, the outbreak of violence as the workers chased, struck, and kicked demonstrators, the attempt by some workmen to charge City Hall only to be rebuffed by a phalanx of policemen, the occasional attempt by a cop to protect a student from blows, and the more frequent refusal of police officers to intervene against rioters many of them identified with. Kuhn understands that by pinning down each incident and phase of the riot, even at the risk of becoming repetitious, he has given historians as well as general readers the most thorough and exacting account of this event yet written.

The book is also good at showing how the Nixon White House shrewdly responded to the riot (and to a May 20 Manhattan rally by perhaps 150,000 hardhats) to consolidate its popularity among those Nixon described as “disaffected Democrats... blue-collar workers... working-class white ethnics” angered by an antiwar movement many viewed as treasonous. By late May Nixon was actively courting “hawkish” New York union leaders, including Building & Construction Trades Council head Peter Brennan, who later became Nixon’s Labor Secretary.

But in addition to being a chronicle of events, The Hardhat Riot is a complaint and an accusation. Kuhn’s authorial stance is to side with blue-collar workers, formerly loyal New Deal Democrats increasingly alienated in the late 1960s by the commandeering of their party by “aloof elites” allied with the antiwar movement, the student New Left, black militants, and the counterculture. To Kuhn, it was affluent young liberals —exemplified on the local scene by John Lindsay, mayor from 1966 to 1973—who alienated loyal white Democrats by abandoning the “pragmatic” worker- and family-centered liberalism of FDR for something far more incendiary. Kuhn traces a nationally significant political trajectory stretching from the Hardhat Riot to the Age of Trump. He blames elite liberals for essentially hijacking the Democratic Party and losing blue-collar voters.

Those of us to the left of center would do well to digest at least a part of Kuhn’s right-of-center argument, the part that underscores how condescending much New Left and liberal Democratic behavior and rhetoric felt to many working- and middle-class whites in New York and across the country. Well-educated liberals appalled by racism got away with stereotyping “the white lower middle class” as “an army of beer-soaked Irishmen, violence-loving Italians, hate-filled Poles,” the writer Pete Hamill argued in 1969. Such disdain, Kuhn contends, drove away white voters who were actually troubled by the war, losing them to the Democratic Party. Kuhn uses both statistical and anecdotal evidence to show just how deeply the Vietnam conflict was a “class war” driving a wedge between working-class volunteers and draftees who bore the brunt of the fighting and more privileged, well-educated men (Bill Clinton and Donald Trump among them) who availed themselves of draft deferments for college students or other loopholes to avoid combat. Having tainted themselves as soft on Communism, friendly to radical militants, and out of touch with the concerns of ordinary working stiffs, the “limousine liberals” of Lindsay’s City Hall (and Democratic politicians nationally) had only themselves to blame for the rise of the Silent Majority (and later, the Moral Majority) out of the ashes of the New Deal Coalition.

Here Kuhn echoes his earlier book, The Neglected Voter: White Men and the Democratic Dilemma (2007), which blamed “dogmatic” (meaning left-leaning) Sixties liberals for jettisoning the “pragmatic liberalism” of the New Deal and its voters, the latter defined by an ethos of personal responsibility, self-reliance, a uniform moral code, devotion to the traditional family, and manly “grit.” Missing from Kuhn’s definition is the daring experimentation with Keynesian strategies, wealth redistribution, and outreach across ethnic and racial lines that characterized FDR’s presidency (for all its mistakes and failures) in the eyes of more liberal historians. The Neglected Voter urges Democrats to recapture “gritty” white male Rust Belt and rural voters by becoming a sort of Trump Lite party but doesn’t explain how they would win elections after throwing their 21st-century “dogmatic liberal” base under the bus.

By adding historical detail to this argument, The Hardhat Riot becomes a victimization narrative, and it’s here that things get problematic. The book aspires to clarity by reducing its protagonists to working-class whites and affluent liberals. It’s a pairing that served as shorthand by the late 1960s: “We’re Staten Island. They’re Scarsdale,” Kuhn quotes a conservative Columbia University student who opposed the leftist student “revolt” there in 1968 — a contrast that spoke not only to class geography but to the gulf separating the values of many conservative outer-borough Catholics from those of liberal suburban and Manhattan-centric Jews. In Kuhn’s view, the post-World War II years were an era in which working-class whites minded their own business and followed the rules. Meanwhile, effete intellectuals such as Adlai Stevenson, elite liberals like Republican-cum-Democrat John Lindsay, and young radicals Mark Rudd and Tom Hayden drove the Democrats further and further left. Kuhn asks readers to comprehend how crises such as the Columbia student takeover, the disastrous 1968 Democratic presidential convention in Chicago, and the seemingly endless series of mass antiwar protests, “ghetto” riots, and liberation movements led straight to the Hardhat Riot by bewildering and infuriating blue-collar New Yorkers and millions of other Americans.

But in history as on the dance floor, it usually takes two to tango, and Kuhn’s accusation is strikingly one-sided. To blame liberals for singlehandedly unraveling the New Deal Coalition by moving too far to the left sidesteps just how complex and messy things were in New York City and elsewhere by the 1960s. True, the Vietnam War was the vortex into which all of domestic politics was sucked after mid-decade. But from its very start in the mid-1930s, the emerging Democratic Party coalition — made up of unionized workers, white urban Catholics, Jews, white Democrats in the Solid South, and African Americans abandoning the GOP (“the Party of Lincoln”) — was a crazy quilt rather than a monolith. Quintessential building blocks of FDR’s working-class electoral clout — unions like Mike Quill’s Transport Workers Union in New York and Walter Reuther’s United Auto Workers in the Midwest — were themselves volatile coalitions, strained by internal rivalries between social democrats, Communists, conservative Catholics, and others. The presence in the TWU of followers of the antisemitic “radio priest” Charles Coughlin and of Klansmen in the UAW meant that issues of racial and ethnic inclusion would be tense by the end of the 1930s.

In New York, the postwar vigor of an array of progressive union locals serving municipal employees, hospital and retail workers, electricians, seamen, and others-- often led by leftists committed to securing civil rights for their increasingly Black and Puerto Rican memberships—would set them on a course different from that of construction and longshore unions whose Irish and Italian majorities viewed them as preserves for family and community members. The growing presence of blue-collar people of color, in fact, remade the city’s labor activism and the meanings of urban working-class identity (a crucial reality ill-served by focusing only on whites). At the same time, lured by the GOP’s brawny anti-Communism and its support for the status quo, large numbers of white New York City Catholics were already voting for Eisenhower over Stevenson and even choosing Nixon over Kennedy in 1960. Meanwhile, a more left-leaning white liberalism was not monopolized by suburban and Park Avenue elites, as Kuhn implies, but was also shared in urban neighborhoods where middle-class professionals and their kids came out against the Vietnam War. The larger point is that the New Deal Coalition was not a communion of like minds unilaterally shattered by the New Left in the late 1960s. Instead, that coalition was itself always a field of battle where more conservative working-class whites (as well as others) signaled their resentments long before the Hardhat Riot.

Race is ultimately the missing link in Kuhn’s story, despite repeated references to it. His implication that elitist liberals unilaterally weakened the Democratic Party by alienating its white working-class constituency during the Vietnam War largely ignores the work of scholars — Joshua B. Freeman, Brian Purnell, Joshua M. Zeitz, Timothy J. Sullivan, Clarence Taylor, Thomas J. Sugrue, and Matthew F. Delmont among them — who have shown how an emerging conservative white militancy in the outer boroughs and a budding student New Left were shaping each other before the war began in 1964. Dogged resistance by white Queens parents against school integration in 1959 and 1964, the concurrent rise of New York’s Conservative Party, police brutality repeatedly inflicted on Black and Puerto Rican New Yorkers, the persistence of illegal housing discrimination (at the hands of Fred Trump and many others) despite activist campaigns, the success of whites-only construction unions in defeating pro-integration protests in Brooklyn in 1963, the resounding defeat by white voters of a measure for civilian review of cases of alleged NYPD brutality in 1966: All helped to foment an accelerating mutual polarization between young “Scarsdale” leftists and “Staten Island” workers. So did Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy” and George Wallace’s third-party “law and order” campaign in 1968, enabling both to capture millions of white votes North and South as the Democrats identifiably became the party of civil rights.

It is fair and useful for Kuhn to remind us of the “Staten Island” side of this coin usually neglected by liberal and leftist commentators. Working- and middle-class whites in New York and across the country did not perceive themselves as racially privileged. Instead, they felt threatened by rising crime rates, rioting, moral permissiveness, leftist flag desecration, and unsettling economic and demographic changes. Their opinions — often critical of both the war and the antiwar movement — were more nuanced than media photo ops and sound bites disclosed. Kuhn quotes a New York City "hardhat” who believed antiwar protesters were “getting carried away” but were not “absolutely wrong,” and another who stated that young leftists “have a right to feel the way they do." Yet the ways in which "hardhat” concerns were entangled with pervasive white resistance to integration and racial equity is largely missing from The Hardhat Riot. It was these inequities that radicalized a generation of young leftist militants — in Scarsdale, Brownsville, Spanish Harlem, and elsewhere — as the civil rights movement met its match in northern cities, and as the word “Vietnam” entered the American vocabulary.

In the end, Kuhn's narrative works better as a vivid history of a seminal moment than as an accusatory polemic. The reader’s own political vantagepoint will shape their response to Kuhn’s overarching complaint. I came away thinking more carefully about the long road leading from the violence in lower Manhattan on May 8, 1970 to that of Capitol Hill on January 6, 2021. That road shadows another path, one winding from the expectations of 20th-century New Yorkers like the German immigrant Trumps of Woodhaven, Queens to the grievances of MAGA supporters. Both roads were paved over decades by impassioned people at different points on the political spectrum — “hardhats,” “dogmatic liberals,” and their ideological offspring — as well as by many others in between.

Steven H. Jaffe is an independent historian whose books include New York at War: Four Centuries of Combat, Fear, and Intrigue in Gotham (2012) and Activist New York: A History of People, Protest, and Politics (2018).