The Problem We All Live With: An Interview with Sarita Daftary-Steel

Today on the blog, editor Molly Rosner speaks to Sarita Daftary-Steel, founder of the East New York Oral History Project, an interview project documenting the experiences of people who lived in East New York during a decade of rapid change from 1960-70.

How did you get involved in this project? What is your connection to East New York?

My own East New York history started, actually, in the early 1900’s when my great-grandparents lived in the neighborhood, along with many other Italian-Americans. I learned this accidentally from my grandmother when I started working in East New York in 2003. I mentioned to her where my new job was, assuming she’d never have heard of it, and she told me that my Great Aunt Millie — her eldest sister — was born in East New York, before they moved to Bushwick, Corona, and eventually Long Island. Like many other working-class white families, the GI Bill and various Federal Housing Administration programs helped my grandfather (a World War II veteran) to purchase his first home in the newly developed suburbs of Long Island. Restrictive covenants (enforced by intimidation and violence even after they were ruled illegal) generally prevented families of color (even veterans) from doing the same.

From 2003-2013, I worked with the East New York Farms! Project, a program of the United Community Centers. Through that work I learned that East New York had (and still has) more community gardens than any other neighborhood in New York City, and that those gardens were cultivated out of the vast areas of abandoned property and vacant land left behind by white flight and disinvestment.

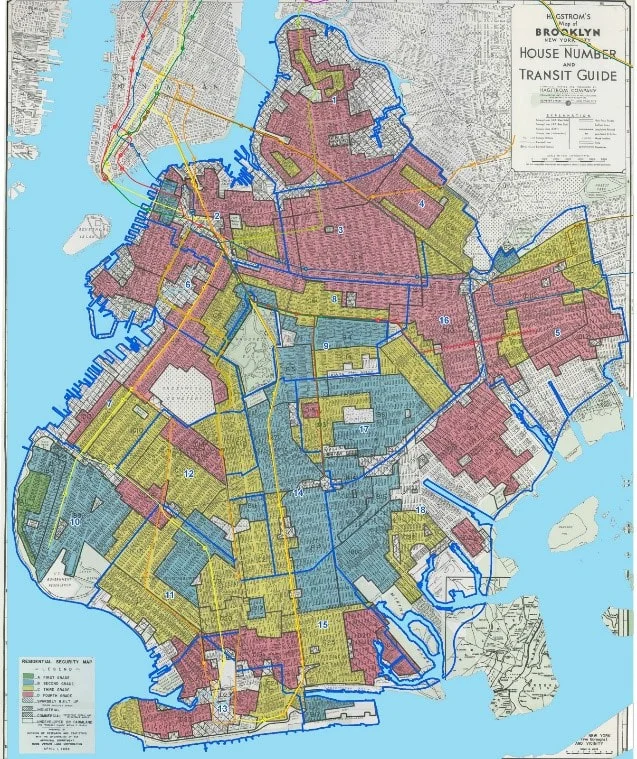

When I tried to understand that history further, I began to learn about the systems and policies that preceded it — policies like redlining and restrictive covenants, and practices like blockbusting and planned shrinkage. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) asked the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), beginning in 1935, to rate the risk of lending money in different neighborhoods of 239 cities across the nation. Communities were rated as A, B, C, or D, with D-rated communities marked in red. The basis for these classifications, noted in 'area descriptions,' was largely racial bias, and xenophobia. While many white immigrant communities were given a D or “hazardous” rating — like East New York, which was primarily Jewish and Italian in the 1930s - the process was also explicitly anti-black, in that almost all areas that received a D rating had “Negro” residents noted as part of that justification, and this sometimes made the difference between an area getting a C or D rating.

As the HOLC's maps were released, they were frequently used as a justification for denying loans and limiting investment in D-rated communities, while the federal government insured home loans in suburban areas, where people of color were prevented from buying homes. This practice would later be termed "redlining."

I also observed the relative lack of documented history about East New York, and started this project partly as an effort to address that.

A Residential Security Map for Brooklyn (Above) and legend from this map (R), created by the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1938.

From one of the HOLC’s Area Descriptions for an area within East New York. Source: Home Owners Loan Corporation Residential Security Map and Area Description, via Mapping Inequality

What are some of the reactions you’ve gotten to this project and how has it impacted your work?

I read a lot of online articles, but my general practice is to try to resist reading the comments, and to definitely not join the fray. Yet somehow my outrage got the better of me when reading an article about a real estate agent who developed a brochure to attract commercial tenants to Fulton Street in Bed-Stuy, and completely omitted black people from the brochure’s images. I posted something about the historical, ongoing, and deliberate destruction of communities of color, and about the oral history project I was working on, which illustrated how another version of this story played out in East New York in the 1960s (and after). Unsurprisingly, someone responded with this comment:

“Way to live in the past! Not for nothing but to constantly bring up things that happened 50 years ago gets old...How about this, you want to live in a desirable area, make more money. As long as you can pay the rent nobody cares what color you are!”

Even aside from those who would actively assert that the events of 50 years ago have no relevance today, we seem to broadly, as a society and even as New Yorkers, have very little understanding of the forces that shaped, and continue to shape, our very segregated communities, even in the North. Along with that comes a general ignorance of the forces that led to the near decimation of black and brown communities — and their wealth — in the post-war decades, while white communities flourished. I think about this every time I hear a young white person (maybe hoping to ease their guilt) posit that gentrification is really about wealth. As in, not about race. As if those two things can be truly separated in this country.

Even for those who recognize this history, there’s still the haunting question of what to do about it. I recall a friend of mine — a white woman and a native Brooklynite — telling me about her move to a largely white neighborhood in New Haven. While it felt odd to live in such a homogeneous community, she noted that it was a relief for once to not to be in the position of gentrifying a black or brown neighborhood.

Why is this history important and how does Oral History change the historical narrative?

I believe it contributes to our understanding of how we got here, and how this history lives in the memory and experiences of real people. From 2014-2015, I conducted interviews with a diverse group of nineteen people who lived in East New York, Brooklyn during the 1960s. The sixties are obviously known as a turbulent decade in New York City and the United States in general. In East New York, it was a time in which the population rapidly changed from predominantly white to predominantly black and Latino. It was this brief window in which East New York was - at least on paper - racially integrated. I wanted to learn more about the lived experience of that period. I wanted to complete this project because East New York is a community that I care deeply about, and because I believe East New York’s particular story can help to illuminate a larger story about segregation, disinvestment, and racial wealth gaps in our City and our country.

What have you learned from this project? What were your most important findings?

Perhaps the single finding from my interviews that most surprised me was how consistently people described to me neighbors of different races getting along quite well — and in some cases living somewhat separate but not generally antagonistic lives. It underscored for me something that I might have known academically but hadn’t fully understood, which is how absolutely crucial was the influence of policies that encouraged segregation — and the speculators that exploited those policies for financial gain. This is not to say that interpersonal racism did not exist or that people did not talk about it in the interviews I collected. Yet, as one narrator put it, selling your house — or even moving out of your long-time apartment, is a major decision, and the stories I heard just did not suggest that enough white people were upset enough about having black and Latino neighbors for that to be the sole, or even primary, reason for their departure en masse. Yet, the white population of East New York’s central area (that which was most uniformly redlined) dropped from over 82,000 in 1960 to just over 43,000 by 1970 and to about 7,000 by 1990.

How does this project connect to today’s housing and zoning issues in New York City?

While I was conducting these interviews, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced his intention to rezone East New York to create higher density housing - the promise being that some affordable housing would come with this. That added a whole new dimension to this project, as I heard residents grapple with the idea that their community - shunned and abandoned for decades - might suddenly be too expensive for them to remain in. Narrator Johanna Brown put it poignantly when she said,

“But people are running back now. If we were included, it would be ok, but nobody’s really concerned about including us. They’re not really. They’ll live among us, and they’ll tolerate us, but eventually we’ll be priced out. We can’t afford to be their neighbors… because there’s an inequity. But on the whole, it’s unfair, it really is unfair.”

Sarita Daftary-Steel worked at United Community Centers for 10 years as part of the food justice and community organizing project, East New York Farms!, and during this time met many long-time community residents with compelling stories about how their community had changed. Sarita currently works on the #CLOSErikers campaign as a community organizer with JustLeadershipUSA, and is a proud East New York resident.

Visit www.eastnewyorkoralhistory.org to explore to clips of interviews (in a map, and timeline format) and link to the Brooklyn Historical Society’s online archive.