The Scenic Designs of Boris Aronson

By Stefanie Halpern

In 1988, director Elia Kazan recalled a story in which he and Broadway scenic designer Boris Aronson drove cross-country together on a research trip for their latest theatrical collaboration. According to Kazan, as they entered New Mexico, Aronson pointed to a single tree growing atop a chain of hills barren of any other vegetation and said, “Without this tree, these hills would not exist.”[1] As single elements, neither the tree nor the hills attract notice. But when taken together, it is the tree that draws the eye to the hills, bringing them into focus, making them relevant. In turn, the singularity of the tree gives dimension to the hills, their imposing size and grandeur heightened by the smallness of the tree, its uniqueness brought into focus by the bareness of the hills themselves.

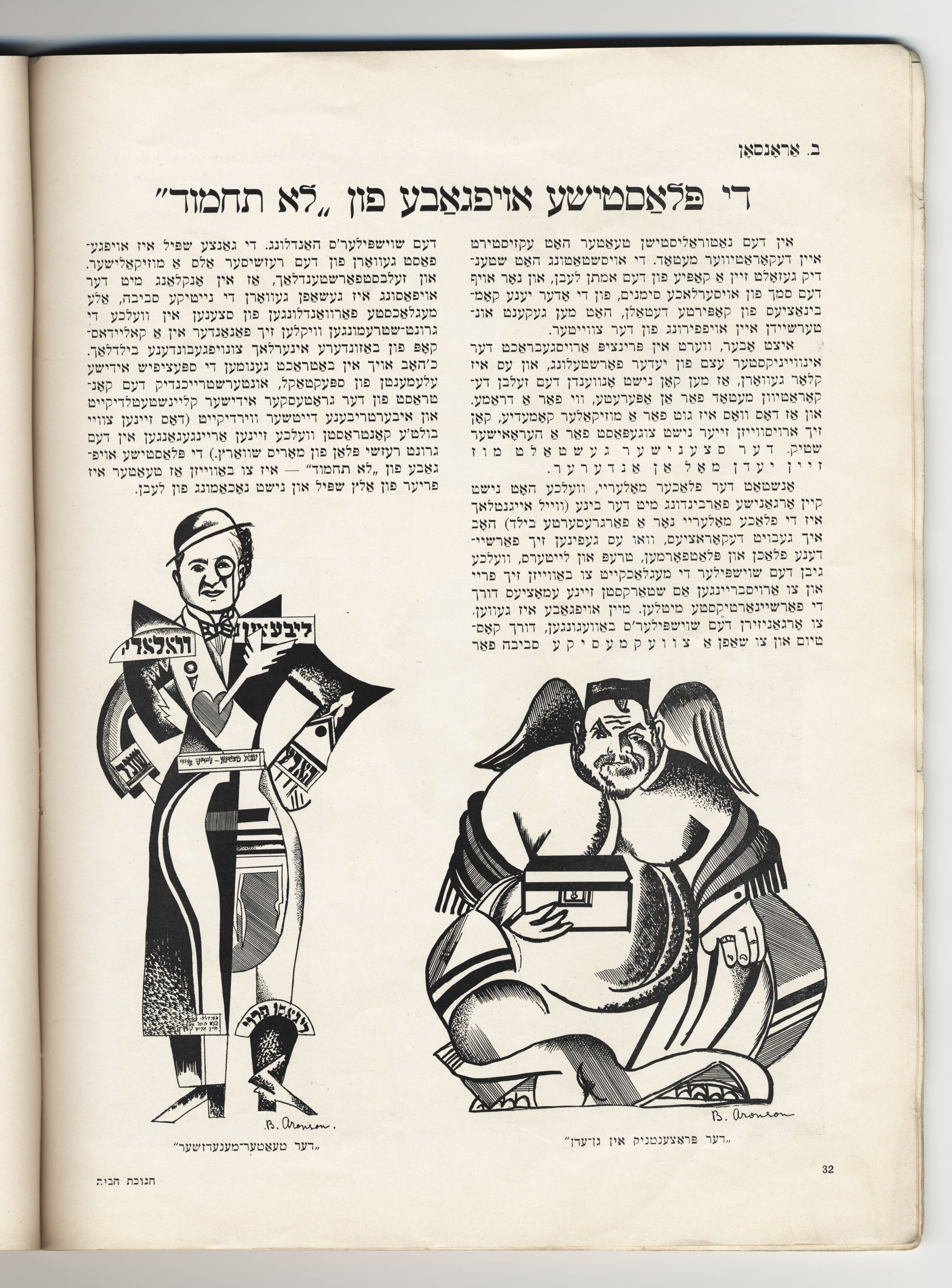

Boris Aronson’s costume sketches for the characters of the Usurer (L) and the Theater Manager (R) in The Tenth Commandment at Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theater, 1927. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Aronson’s enigmatic statement to Kazan is in line with his theories on scenic art and stage design developed over a forty-year career in the American theater. For Aronson, a stage design was unified and complete only when color, lighting, objects, bodies, movement, voice, and sound were all working in tandem with one another, highlighting and bringing each element into focus. Aronson’s work on iconic shows like Awake and Sing, Cabaret, The Diary of Anne Frank, The Crucible, Company, Follies, Fiddler on the Roof, and more than 100 others would help define the American stage aesthetic of the 20th century American.

Born in Kiev in 1900 to a traditional Jewish family, Aronson’s formal art training began in earnest after the 1917 Russian Revolution when Kiev became a center of the avant garde art movement. During this time, Aronson studied under Alexandra Exter who schooled him in various artistic styles, training which he would later put to use in the sets he designed. Aronson joined a milieu of Jewish artists who were attempting to create a distinctly Jewish national art style by blending classic Jewish folk elements with avant garde artistic styles. The interplay between the old and the new, tradition and modernity, ritual and theatricality, the visible and the unknown, would continue to exert an influence over Aronson for the duration of his career in America.

“Little House in the Woods” set designed by Boris Aronson for The Tenth Commandment at Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theater, 1926. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

When Aronson immigrated to America in 1920, American stage design was making a distinct turn away from the overly detailed naturalist sets of the 19th century popularized on Broadway. In the rejection of both naturalism and the static painted backdrop, the New Stagecraft, as it was known, strove for three-dimensional sets that were either purely imaginative or that merely suggested actual locations, wholly omitting the representation of place or only hinting at it. Everything deemed unnecessary was stripped from the sets. Through sparse and emblematic elements, the sets were meant to suggest an atmosphere rather than something purely realistic. Design became a visual language that bridged theatrical stages and everyday landscapes. Modern design moved the stage away from the illusionistic world created by romanticism and realism and brought it into a theatrical realm where the image came to function as an extension of the themes and structures in the text, whether implicit or explicit.

Designers working under the principles of the New Stagecraft sought to establish a mood or atmosphere appropriate to the production using line, mass, color, and light. Text, movement, costumes, and designs were all meant to merge into a single emotional whole. Unlike the naturalist set which gave only a sense of place, the New Stagecraft set, using a particular concept or metaphor, was supposed to be the spiritual essence of the play. Because the elements of the set were not meant to be viewed as an extension of the world but rather as a metaphor for something in the everyday, the setting had the potential to shape the entire tone of the production, determining the mood, movement, interaction of the characters, and even the interpretation of the script, seeking to visually and metaphorically encompass the world of both the play and the audience within a unified image.[2]

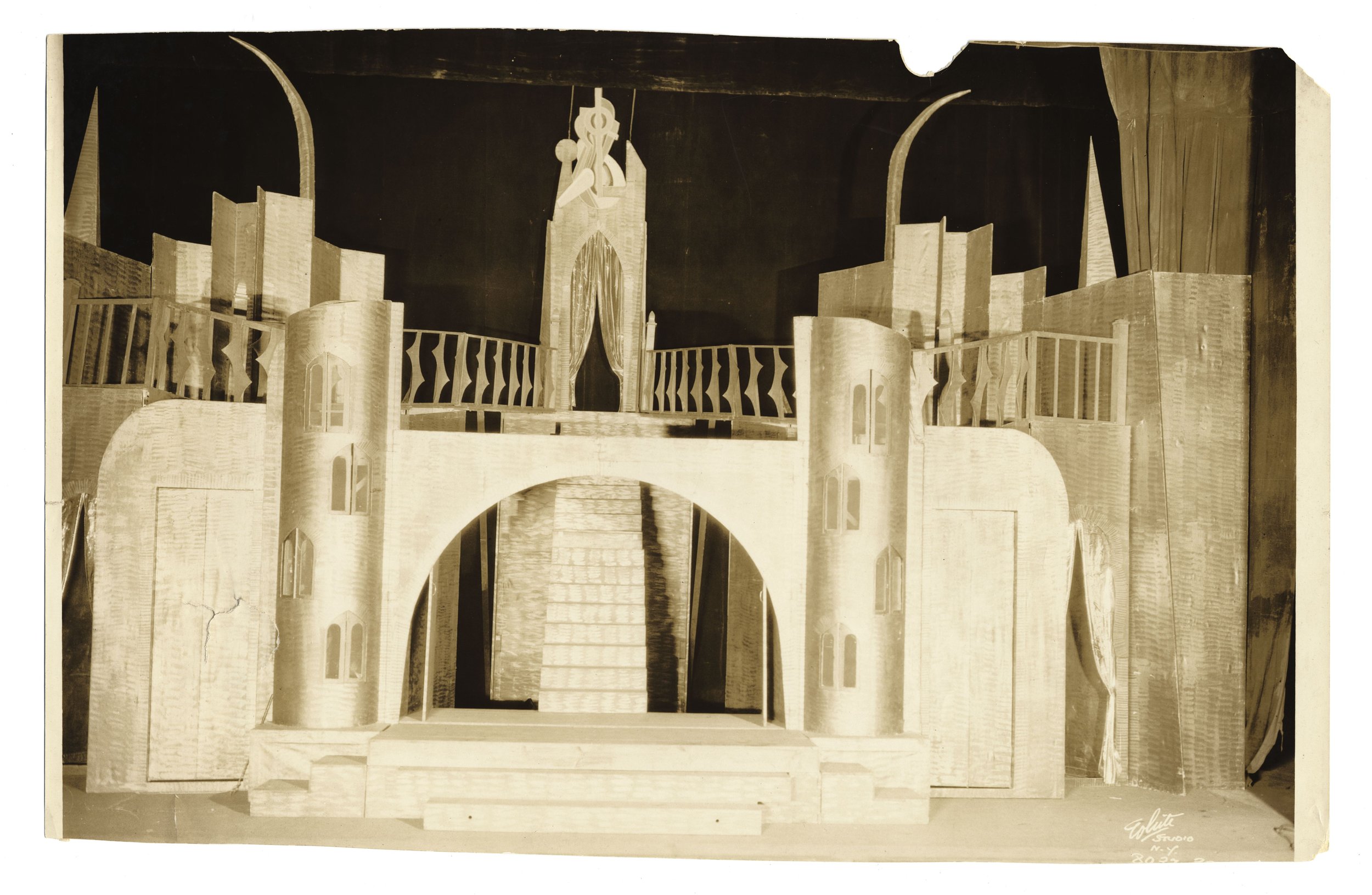

Set design for Mathilda’s Castle created by Boris Aronson for The Tenth Commandment at Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theater, 1926. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Aronson, working within these New Stagecraft principles, designed his first sets in America for New York’s Yiddish theaters. His most notable Yiddish stage design came in 1926, when he was asked to design the opening production for Maurice Schwartz’s new Yiddish Art Theater building on Secong Avenue and 12th Street. Maurice Schwartz chose to stage an adaptation of Abraham Goldfaden’s Dos tsente gebot (The Tenth Commandment), originally written in three acts in the mid-1880s by Abraham Goldfaden. The basic plot of the play revolves around the struggle between the Angel of Good and the Angel of Evil attempting to have two Jewish couples — one traditionally religious and one modern and secular — uphold or break the tenth commandment. The play was one of epic proportions involving twenty-five scene changes, 360 costumes, and dozens of masks donned by the actors.

The opening scenes of the play were staged to take place in what one might expect a traditional small town Jewish home to look like. Upon closer inspection, however, it became immediately obvious that something about Aronson’s set was out of joint. The exterior of Aronson’s design revealed windows hung at odd angles, shutters and panes askew. The walls of the home were not straight, but seemed to sag, their stability suspect. Using the newest available technology, Aronson designed the walls of the house to open to reveal the interior. This design element was new to the American stage, and Aronson would replicate it again forty years later in his sets for Tevye’s house in Fiddler on the Roof.

The interior of the house contained typical domestic items — a clock, a portrait, tables and chairs, candlesticks, even decorative wallpaper. Though these items were all meant to be true to the period of the play and the lower economic class of the characters, Aronson chose to paint them on the walls of the house rather, creating representations rather than reality. For Aronson, the decision to paint these objects on the walls was both practical and symbolic. Because the house folded open and closed, painting the objects proved more effective than affixing the actual objects to the walls. In addition, they brought the theatricality of the set to light, their unnaturalness adding to the overall tone of the scene. The house itself became a central component in the play, a character with its own personality.

Actors in costumes designed by Boris Aronson for The Tenth Commandment at Maurice Schwartz’s Yiddish Art Theater, 1926. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

To complete the carnivalesque atmosphere of the play and the macabre quality of the designs, Aronson’s costume designs were a blend of traditional religious imagery and modernism. For example, he dressed several of the chorus members in what appears, at first glance, to be traditional Hasidic garb. But instead of sleeves and stockings, Aronson used fabric made to look like Torah scrolls, commenting on the desecration of religious law and ritual that serves as the backbone of the play. For the character of “A Hypocrite,” Aronson designed a costume that embodied the two sides of man. One half was the traditional long coat of a religious Jew, the other a short and modern suit.

After one of the characters is convinced by the Angel of Evil to commit adultery, he makes a descent into hell. By far Aronson’s hellscape was the most impressive set created for the play. Aronson designed hell to be the shape of a giant human head. According to Aronson, this was done because “the conception [of hell] is mental.” Here, according to Aronson, he drew inspiration from the reality of the Yiddish theater audience: “The actual Hell is a factory on a hot day—one which the audience of this play could well appreciate. The construction is of a fire escape, which is a symbol of trouble and emergency.”[3] For an American immigrant audience intimately familiar with the grueling conditions of the factory and sweatshop, the set immediately symbolized the “moving force of industry, the flame of labor and passion, the steps of endless grueling labor.”[4] What is more, Aronson painted the wooden frame of the head a fiery red, symbolizing not only the flames of hell but also perhaps the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, an association that would not have been lost on the audience. Added to this was the use of stark contrast lighting which illuminated the actors from below, casting the already grotesque faces of the devils and demons and lost souls in eerie shadow. According to Aronson, “The actors could slide down the pole from a platform above, come to the staircase away from the audience’s gaze, and climb the fire escapes to the platform again; thereby, each appearing as several people. Twenty actors gave the effect of hundreds in this set.”[5]

The final scene of the play was designed as a lavish and ornate theater. Everyone in heaven was meant to have their own plush red velvet covered box seats. While the main action was happening onstage, separate movements and stories could play out in the individual boxes, each their own miniature stage with curtains and an arch that formed a proscenium within the proscenium, a theater within a theater within a theater. The epitome of luxury and decadence, Aronson again drew from the city itself and designed heaven to be reminiscent of the Metropolitan Opera House.

It was this production that catapulted Aronson onto the American mainstream stage. Though critics considered the play an “unfortunate” choice for the opening of Schwartz’s new theater, Aronson’s sets were acknowledged as “colorful and ingenious.” The sets proved one of the best features of the play. In Theatre Arts Monthly, critic John Mason Brown said of Aronson’s sets and costume designs:

The settings and costumes are the bravest experiments in scenic design that the present season has disclosed. Aronson’s endless costumes are thoroughly thought out in individual detail as well as being tonal factors in the large ensembles. By employing not one, but many constructivist settings, which range from heaven to hell, he conditions the style of the entire production, and brings a welcome vigor and originality to our theatre.[6]

Aronson’s designs for The Tenth Commandment drew increased public and critical awareness to his work. This, coupled with a number of gallery shows exhibiting both his theatrical designs as well as his paintings allowed Aronson to gain legitimacy as a scenic designer in America as theater critics increasingly considered Aronson’s sets to be the most innovative seen on any American stage. Writing in 1929, several years before Aronson designed anything for Broadway, a critic for the New York Times wrote of Aronson’s designs:

It is something of this radically modern vision that grips us in the work of Boris Aronson. He has been able to wrest, in some degree, the secret essence of steel, cement, height and angled form that, compounded, forms what we choose to term the typically American. It is his ability to express life in our terms that make of special interest his stage designs.[7]

A year after the production of The Tenth Commandment, Aronson was hired to design his first set for the mainstream English-language stage.

Stefanie Halpern is the Director of the YIVO Archives.

[1] Elia Kazan, “Mes principaux collaborateurs artistiques,” Positif, September 1988, 55-56.

[2] Arnold Aronson, Looking Into the Abyss (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2005), 14. There is no relation between Boris Aronson and Arnold Aronson.

[3] Boris Aronson, Scrapbook, box 148, folder 4, Boris Aronson Papers and Designs 1923-2000, Billy Rose Theatre Division of the New York Public Library (New York, NY).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Frank Rich, Theatre of Boris Aronson (New York: Random House, 1990), 10.

[6] John Mason Brown, “The Tenth Commandment,” Theatre Arts Monthly, 1927, 90.

[7] “A Designer of Stage Settings Who Began at the Beginning,” New York Times, 17 March 1929.