“'The World's Most Arrested Lesbian:' Corona Rivera and the New York Gay Activists Alliance, 1970-72.” An Interview with Marc Stein

Interviewed By Ben Serby

Today on Gotham, Ben Serby interviews Marc Stein about his research into the life and activism of Corona Rivera, who spent formative years in the Gay Activists Alliance in New York in the early 1970s. This research was recently published as a digital history exhibit for Queer Pasts and is available here.

Who is Corona Rivera, and how did you become interested in her? Why should other historians of LGBTQ activism become familiar with her story?

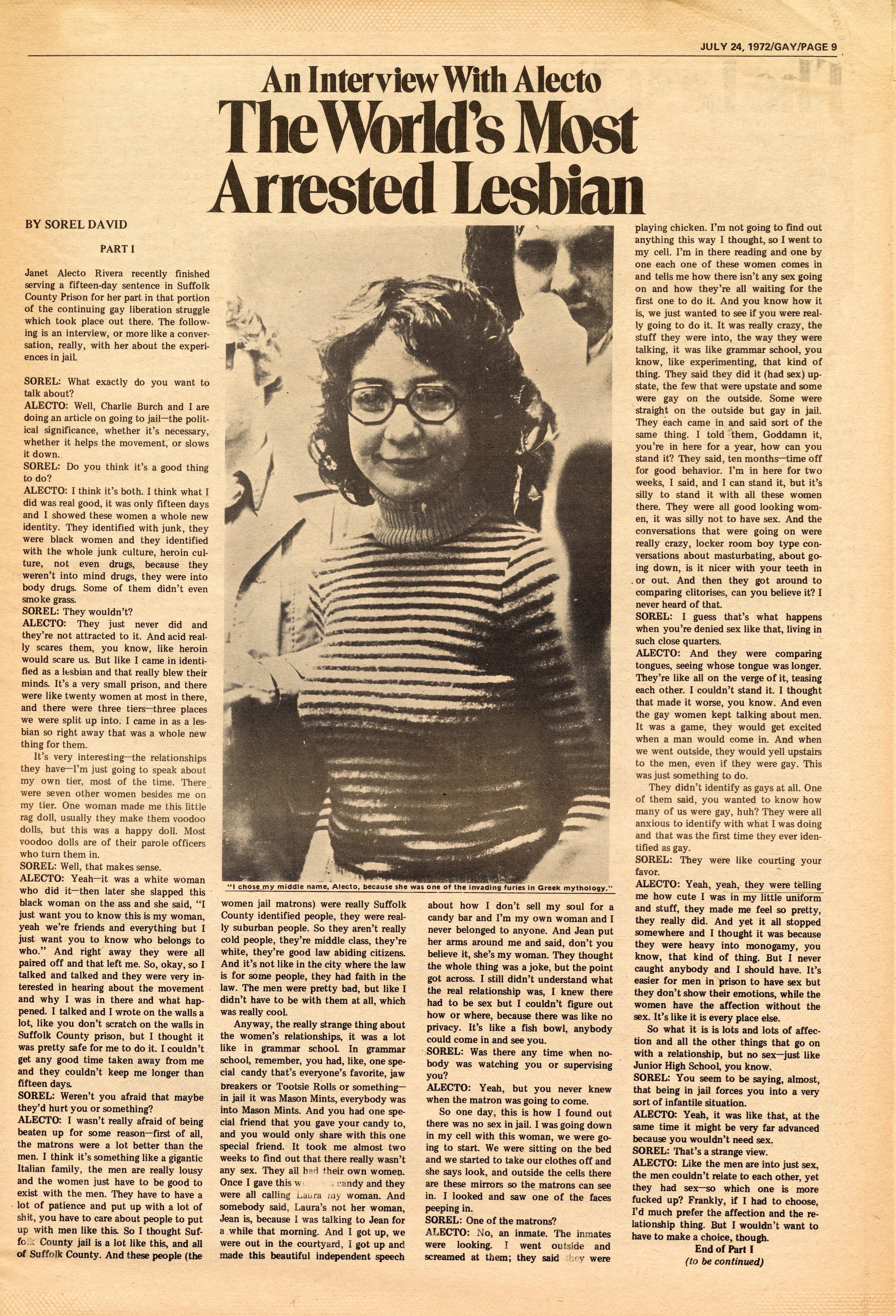

A few years ago, while working on the second edition of my Routledge book Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (2023), I came across a two-part interview in the New York-based newspaper GAY. Published in 1971, the interview was titled “The World’s Most Arrested Lesbian.” I was immediately suspicious of the truth of the hyperbolic claim, but I was intrigued. The article was about “Janet Alecto,” a.k.a. Corona Rivera, who recently had served time in the Suffolk County jail after suburban police in Hauppauge attacked her and other New York City Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) members as they tried to submit witness statements about police brutality during a recent Long Island gay bar raid. I eventually found a few dozen mainstream and LGBTQ+ media stories about Rivera, most of which focused on her participation in GAA direct action protests and her multiple arrests in 1971 and 1972.

As a historian of social movements, I was drawn to the depictions of her incredible physical courage and strategic intelligence in hostile contexts. In one noteworthy instance, for instance, Rivera had handcuffed herself to a railing at Radio City Music Hall so that she could not be removed easily or silenced quickly during a GAA protest at a presidential campaign fundraising appearance by New York City Mayor John Lindsay, and she repeatedly had confronted police officers and government officials during demonstrations, sit-ins, and marches. As a scholar whose first book focused primarily on relationships between lesbians and gay men, I was curious about how she functioned as a woman in a predominantly male organization. As an oral historian, I was grateful when former GAA president Rich Wandel put me in touch with Rivera and when she agreed to participate in an interview. (We both now live in the Bay Area, but we did the interview via Zoom because of Covid-19.) As an anti-racist scholar with a Cuban American partner and a long list of publications that address queers of color, I was fascinated when Rivera described to me her evolving understanding of her familial background—first Italian American, then Italian and Cuban American, and then Italian American and Puerto Rican. And as a historian of the 1969 Stonewall riots and the LGBTQ+ movement, in and beyond New York, I wondered how I could have missed her story in one of the epicenters of gay liberation.

Sorel David, “An Interview with Alecto: The World’s Most Arrested Lesbian,” GAY, 24 July 1972, 9.

I think historians of LGBTQ+ activism should become more familiar with Corona’s story because it’s fascinating in and of itself, but also because it might change the way we think about the history of GAA-New York and the broader history of LGBTQ+ activism in the 1970s. More generally, I think GAA-New York was responsible for one of the most creative and powerful waves of direct action ever seen in the United States, with lessons for LGBTQ+ and other activists today. Corona was a leading GAA-New York activist for two years and we should know more about her.

You emphasize the fact that Rivera was featured in a number of news articles from the early 1970s, and yet historians of LGBTQ activism have failed to notice her, let alone recognize the significant role she played in the gay liberation movement in New York City. What accounts for this omission?

There is no denying that GAA-New York was predominantly male and white, and I think historians have been correct in saying that. There is also no denying that the primary sources on which historians of GAA rely—primarily media accounts and organizational records—tended to privilege gay white men. My new Queer Pasts exhibit demonstrates that there were multiple media accounts that referenced Corona, but there were far more that marginalized women. One source that I use, from the Gay-Women’s Liberation Front Newsletter, illustrates some of the ways that GAA men were responsible for some of this (taking undeserved exclusive credit for movement successes), but journalistic biases and prejudices also were at play. For all of these reasons, it is understandable that early LGBTQ+ historians would not have paid much attention to Corona. And it is also important to point out that digitization of historical materials has created research possibilities for us today that simply did not exist in the past.

I think there are other compelling reasons to avoid simplistic critiques of earlier historians for missing Corona’s significance. For example, Toby Marotta, who wrote one of the first scholarly studies of GAA New York (in The Gay Militants), did groundbreaking work on the history of New York lesbian feminism in the 1970s. So it would not be accurate or fair to say that Marotta did not care about lesbian history; in fact, he and other early historians of LGBTQ+ activism were leaders in criticizing sexism and racism in the LGBTQ+ movement. I think one of the things at play here is the fact that historians of lesbianism in the 1970s have understandably focused primarily on the history of radical lesbian feminism—on groups such as Radicalesbians, the Furies, Dyketactics, and Olivia Records, and on the rise of lesbian and feminist bookstores, businesses, collectives, communes, and cultures. Lesbians who worked in predominantly male organizations may have seemed less interesting and less representative to many historians. As for how and why previous scholars interested in LGBTQ+ people of color have missed Corona’s story, I think there are complex factors involved. First, there’s the fact that Corona’s own sense of herself as first Cuban American and then Puerto Rican was evolving in the early 1970s, having only recently learned that her Italian stepfather was not her biological father. There’s also the specific complexities of Latina/e/o/x racial identities. Today it might be common to view all Latina/e/o/x people under the “people of color” umbrella, but that was not necessarily true in the 1970s, which is a helpful reminder about ongoing social constructions of race.

Despite her identity as a Latina lesbian, Rivera was involved in the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA-New York), an overwhelmingly male and white organization. You write that scholars have tended to emphasize the sexism and racism of such organizations, discussing women and/or people of color primarily in relation to feminist, lesbian, and POC groups. This has unintentionally marginalized people of color and lesbians, like Rivera, who chose to remain in predominantly white male organizations. How might the experiences of such individuals complicate our understanding of the racial and gender politics of the gay liberation movement?

This relates to a consistent concern of mine: how do we acknowledge white, male, and cis predominance in various LGBTQ+ organizations (and the racism, sexism, and anti-trans politics often associated with those demographics) without erasing the experiences of people of color, female, and trans people who chose to work within those organizations? When, for example, I see the pre-Stonewall homophile movement described as a white, male, cis, middle class, and conservative movement, I wonder why it’s apparently so difficult to use words like “mostly” or “predominantly.” I worry as well about the marginalization of movement “minorities” and I am puzzled when scholars who think of themselves as radical erase radical histories. I also think about the historical scholarship I’ve read that distinguishes between movement “leaders” and movement “participants” or between periodical authors and periodical readers. I believe we need to be attentive to these and related issues if we want to democratize our historical methods and practices.

In this particular case, I think Corona’s story helps us think about GAA masculinism and whiteness, the diversity of lesbian and LGBTQ+ Latina/o/e/x politics in the 1970s, the gender politics of LGBTQ+ movement strategies, the experiences of LGBTQ+ political prisoners, the connections between the gay liberation movement and lesbian parenting activism, the afterlife of GAA-New York, historiographic inclusions and exclusions, and more.

Corona Rivera at a Gay Activists Alliance demonstration in Hauppage, Long Island, 14 December 1971, photograph by Richard Wandel, courtesy of the LGBT Community Center National History Archive in New York City.

Historians of LGBTQ activism in this period have generally studied major cities while neglecting suburban and rural communities and smaller cities, especially those that are poor and working-class. Although she lived in New York City during the early 1970s, Rivera’s political activities brought her all over the state. You write, for instance, that while serving a fifteen-day jail sentence in Suffolk County, Long Island, she befriended a number of incarcerated women, half of whom she identified as lesbians and most of whom were African American. How does Rivera’s story alter our understanding of the geographic dynamics of the gay liberation movement?

For another project jointly published by Queer Pasts and OutHisory, I have documented nearly 800 LGBTQ+ direct action protests from 1965 through 1974, and my research team is hard at work on an update that will include 1975 later in 2024 and 1976 in 2025. One of my motivations in developing that project was to document and encourage further research on the incredible wave of LGBTQ+ direct action that occurred in this period, but I also wanted to redirect our collective attention away from better-known protests and toward under-studied examples of direct action in lesser-known locations. This type of work is typically framed as studying the rural and the non-coastal, but I think there’s also a need to focus our attention on other locations that take us beyond Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. Even work on these urban centers tend to privilege central city cores. In New York, Hugh Ryan has helped shift our attention from Manhattan to Brooklyn, but that still leaves three understudied New York City boroughs, and what about the New York City suburbs, including the northern ones where I grew up and the Long Island ones where Corona was arrested? Corona spent part of her childhood on Suffolk County, so when she joined GAA-New York and GAA-Long Island activists at the protest against police harassment and violence in Hauppage, she was “returning home” and risking family conflict, which sure enough erupted in the aftermath of her arrest. And when she refused to accept GAA’s offer to cover her fine because she wanted to test her commitment to the cause and learn about carceral conditions, she ended up having a fascinating set of experiences in a suburban county jail. Corona’s story helps us place New York City gay liberation within a more metropolitan framework that includes northern New Jersey, Long Island, and the Hudson Valley. Her participation in a march from New York City to Albany, as part of a state-wide lobbying campaign focused on the state capital, and her participation in a meeting of the New York State Coalition of Gay Organizations in Buffalo remind us that gay liberation in “the city” (as we referred to New York when I was growing up) had important connections to gay liberation elsewhere in the state.

After leaving New York for the Bay Area in 1972, Rivera went on to join the Lesbian Mothers Union and participated in a women’s center and a feminist daycare. To what extent do these activities mark a continuity with her earlier career as an activist in the gay liberation movement?

I see both continuity and discontinuity. With respect to continuity, Corona literally became pregnant via a sexual experience with a bisexual man she had known from her LGBTQ+ activist networks in New York. When she traveled to southern California to have an abortion, she stayed with women from that same network. When she decided to abort the pregnancy and move to the Bay Area, she again found community and support with LGBTQ+ people she had known in New York. And when she found herself struggling as a single lesbian parent, she drew on some of the lessons she had learned in the New York gay liberation movement, most especially by joining together with others for social support and political engagement, this time focused primarily on lesbian parenting.

Just as important were the many discontinuities. In leaving Greater New York, Corona left behind her family of origin, with which she was already estranged; it took decades for partial reconciliations to occur. As a single parent, Corona now had to provide for two instead of one. Parenthood, and especially single parenthood, rendered her less “free” to risk arrest and jail time. I also have the sense that Corona was burned out on GAA-style activism by the time she left New York. Her engagement in gay liberation had been intense and exhausting, and I don’t think she was inclined to get involved with another predominantly gay male organization in which she would have had to struggle against gay sexism.

All of that said, while Corona left GAA-New York, I don’t think that GAA-New York ever left Corona: it has continued to serve as a source of influence and inspiration for her, and she has reconnected with many former friends and allies via GAA-New York reunion Zooms that began during the Covid-19 pandemic. Corona left her mark on New York, but New York left its mark on Corona.

Marc Stein is the Jamie and Phyllis Pasker Professor of History at San Francisco State University. He also is the vice president of the Organization of American Historians, the director of the OutHistory website, and the co-editor, with Lisa Arellano, of Queer Pasts (ProQuest). He is the author/editor of eight major publications: City of Sisterly and Brotherly Loves: Lesbian and Gay Philadelphia (2000); Encyclopedia of LGBT History in America (2003); Sexual Injustice: Supreme Court Decisions from Griswold to Roe (2010); Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement (2012/2023); U.S. Homophile Internationalism (2017); The Stonewall Riots: A Documentary History (2019); and Queer Public History: Essays on Scholarly Activism (2022). His primary source exhibit “‘The World’s Most Arrested Lesbian’: Corona Rivera and the New York Gay Activists Alliance, 1970-1972” was recently published by Queer Pasts.

Benjamin Serby is an Assistant Professor in the Honors College at Adelphi University, where he teaches American History and the interdisciplinary humanities. His article, "‘Not to Produce Newspapers, but Committed Radicals’: The Underground Press, the New Left, and the Gay Liberation Counterpublic in the United States, 1965–1976,” was published in the Journal of the History of Sexuality last year.