Engineering America: The Life and Times of John A. Roebling

Richard Haw, interviewed by Beth Harpaz

The beloved Brooklyn Bridge was one of the most daring feats of 19th Century engineering. The man who designed it was equally daring and a paradox of personality: An oddball who engineered a structure that was a marvel of stability at a time when suspension bridges routinely fell down. Richard Haw, a professor in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, has written two previous books about the Brooklyn Bridge. The focus of his latest – after 13 years of research – is the man behind the bridge. Engineering America: The Life and Times of John A. Roebling tells one of the most fascinating American immigrant stories. Haw talks about it with Beth Harpaz, editor of CUNY SUM.

Read MorePublic Works: Reflecting on 15 Years of Project Excellence for New York City

Reviewed by Fran Leadon

“Public Works: Reflecting on 15 Years of Project Excellence for New York City,” on view at the AIA Center for Architecture, on LaGuardia Place, (before the Center closed for COVID-19) is a tiny exhibition about a big idea. In 1996, during Rudy Giuliani’s first term as mayor, the city created the Department of Design and Construction (DDC) in order to unify construction programs that had previously been scattered through the Transportation, Environmental Protection, and General Services departments. In 2004, under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the DDC started a program called “Project Excellence” (also, confusingly, referred to as “Design and Construction Excellence.”)

Read MoreDensity’s Child: How Housing Density Shaped New York

By Katie Uva

New York is a city defined by its density. Manhattan, with its unique geographical constraints, grew rapidly over the course of the 19th century; by 1890, Jacob Riis noted in How the Other Half Lives that the borough as a whole held 73,299 people per square mile and the Tenth Ward, the densest portion of the Lower East Side, held 334,080 people per square mile. This density was visible in multiple ways; in the innovative, epoch-defining skyscrapers that began to jut out of the Battery and Midtown but also cast worrying shadows on pedestrians below; in the tenement districts with their vibrant street life and their disturbing tuberculosis and fire rates. The 20th century would prove to be a time of experimentation and contestation when it came to density. New York would grow further outwards and further upwards, and would be shaped by the tension between density and sprawl.

Read MoreThe Decorated Tenement: How Immigrant Builders and Architects Transformed the Slum in the Gilded Age

Reviewed by Paul Ranogajec

Violette’s important book opens a new chapter on urban housing in architectural history and helps the reader understand a whole set of buildings—indeed, whole swathes of the cityscapes of both New York and Boston—that are prominently visible but often overlooked. Amplifying elite architects’ and reformers’ disdain for so-called tenement “skin-builders,” architectural historians have studied in detail bourgeois design but have paid much less attention to buildings built by and for the working class. The Decorated Tenement helps to correct the historical record, treating the immigrant-built tenement commensurate with its prominence in the two cities. It is a timely book for that, even if the author does not explicitly make the connection to today’s immigration debates.

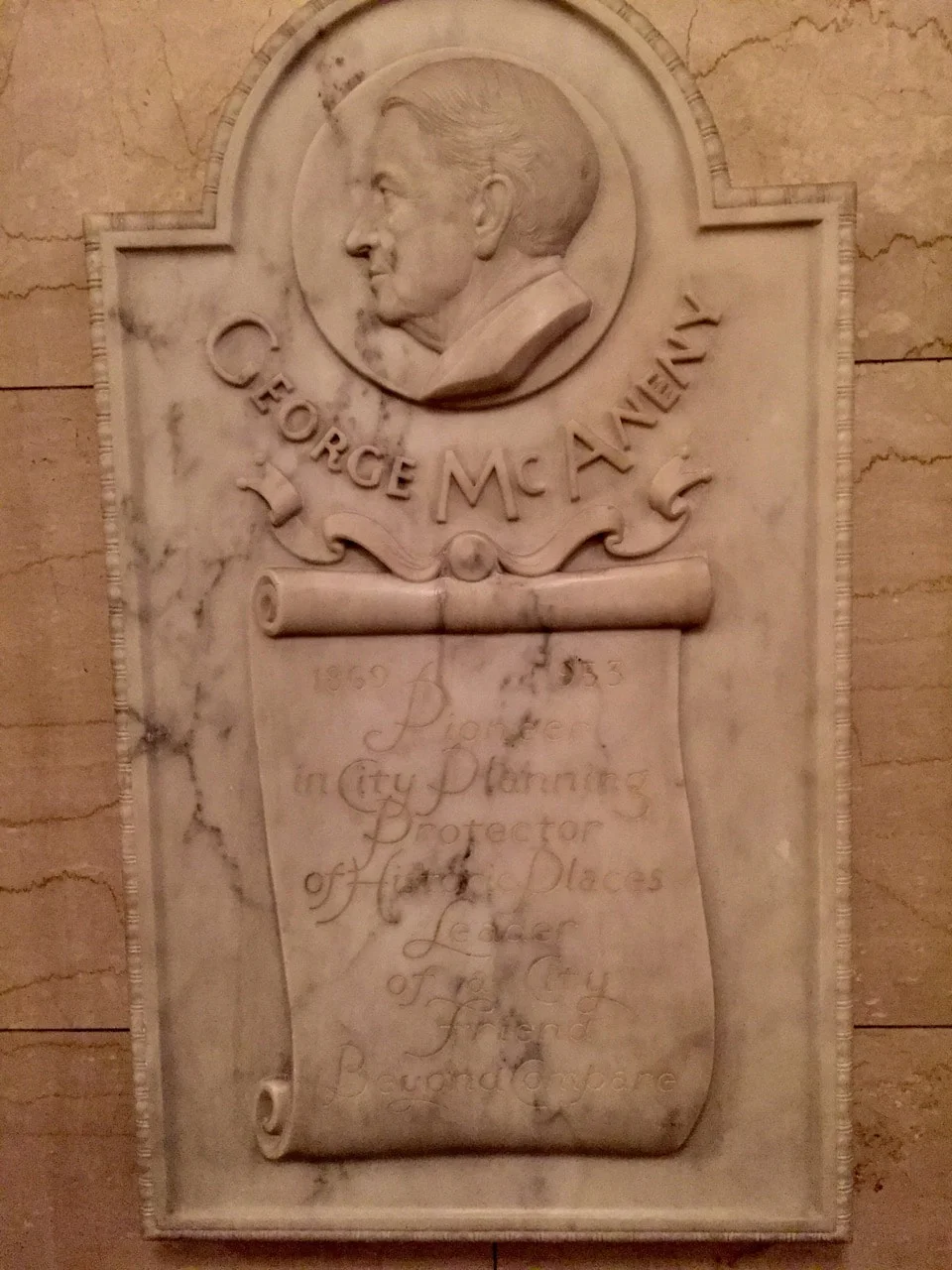

Read MoreRemembering George McAneny: The Reformer, Planner, and Preservationist Who Shaped Modern New York

By Charles Starks

The power to shape the built environment on a metropolitan scale is inevitably shared, contested, and compromised, especially in a city-region as large, diverse, and fragmented as New York has been for the last two centuries. Despite the fervent wishes of more than a few of its leading citizens, the city has never been friendly ground for would-be visionaries seeking to brusquely mold the city’s form to suit their wills—the tech mogul Jeff Bezos being only the latest to find himself chagrined by Gotham’s aversion to imperious planners.

Read MoreSuzanne Hinman's The Grandest Madison Square Garden: Art, Scandal, & Architecture in Gilded Age New York

Reviewed by Paul Ranogajec

Madison Square Garden was among the premier places to see and be seen in New York City at the turn of the twentieth century. As Suzanne Hinman amply documents in her new book, this palace of popular entertainment was truly a modern wonder of architecture and spectacle. Like the old Penn Station (another McKim, Mead and White building that sadly no longer graces the city’s streets) the Garden helped define the aesthetic and social landscapes of New York in the years around 1900.

Read MoreThe Outcast: A Review of Wright and New York by Anthony Alofsin

Reviewed by Fran Leadon

Frank Lloyd Wright didn’t care for cities. In his 1954 manifesto The Natural House, he advised prospective homebuilders looking for land to “go as far out as you can get . . . way out into the country—what you regard as ‘too far’—and when others follow, as they will (if procreation keeps up), move on.”

Read MoreSchlep in the City: Forest Hills

By Frampton Tolbert

Queens is a borough of enclaves, each distinct. While the borough was formed in 1897, development did not begin in earnest until the 1920s, when the population doubled to more than one million people.[1] For this increase in population, buildings were needed for people to live, work, go to school, and worship—and some of which were defining examples of early modern design. While people may think it was Manhattan where this architecture was focused, Queens definitely exemplifies this as well.

Read MoreWhen Long Island City Was the Next Big Thing

By Ilana Teitel

For about a hundred days this winter, Long Island City was in the spotlight as a neighborhood about to be transformed. Amazon was coming, the national media was running articles about the 7 train, and brokers were selling condos via text messages. The word was out about this patch of western Queens and its waterfront views, central location, cultural diversity, and overtaxed infrastructure.

And then, on Valentine’s Day, it was over. Amazon pulled out and locals began to debate whether that much change would have been good or bad for LIC. But, this wasn’t the first time that Long Island City was the neighborhood that almost, maybe, soon, was about to take off. Here’s a look at three other times that LIC was briefly New York’s Next Big Thing.