“The Scourge of the ‘90s:” Squeegee Men and Broken Windows Policing

By Jess Bird

There is perhaps no other bogeyman of New York City’s “bad old days” that has incited greater ire than the squeegee man. Cars created a sense of safety, of separation from the unruly world of the street, but a window washer approaching a car stopped at a red light ruptured that sense of safety, incited panic, and demonstrated, to some, a breakdown in law and order. Squeegee men, “the scourge of the ‘90s,” symbolized the need to be tough on crime, regardless of the costs. Unsurprisingly then, the so-called squeegee pest featured heavily in the mayoral race of 1993, a rematch between incumbent Mayor David Dinkins and Rudy Giuliani.

Read More“God is Forgotten, and the Soldier Slighted”: New York City’s Golden Hill and Nassau Street Riots and the Affective Rhetorics of Crowd Violence

By Russell L. Weber

Winter’s chill clutched New York City the morning of January 19, 1770. Such unwelcoming weather might have persuaded some New Yorkers to remain indoors, supply their stoves with more kindling, and delay their trip to the market until warmth returned to either their bones or their city. The soldiers of Britain’s 16th Regiment of Foot, however, ignored January’s harsh bite. As these regulars made the half-mile walk from their barracks to Fly Market, their enraged, boiling blood kept them warm.

Read MoreIn Service to the New Nation: An Interview with Robb K. Haberman of The John Jay Papers Project

Interviewed by Helena Yoo Roth

Few political leaders in the revolutionary and early nationals eras were more influential than John Jay (1745-1829). A New Yorker born and bred and a 1765 graduate of the nascent King’s College, this austere lawyer of Huguenot and Dutch descent went on to lead a life marked by continuous service and a steadfast devotion to his family, state, and country. The John Jay Papers Project based at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Columbia University has documented Jay’s life through a series of published volumes containing his personal correspondence and public papers.

Read MoreParty Profits: Political Machines as Money-Making Ventures in Gilded Age New York

Reviewed by Atiba Pertilla

The 2020 presidential campaign is coming to a close with controversies swirling over the alleged and established entanglement of the two main candidates, Joe Biden and Donald Trump, in a variety of schemes to use their political position to benefit themselves or their families. At the heart of these concerns lies a conviction that profiting from political connections is a primary driver of Americans’ loss of faith in their elected representatives. Electoral Capitalism, a new book by Jeffrey Broxmeyer, focuses on public graft and political machines in Gilded Age New York and is a timely look at how earlier voters faced similar questions.

Read MoreMonuments of Colonial New York: George III and Liberty Poles

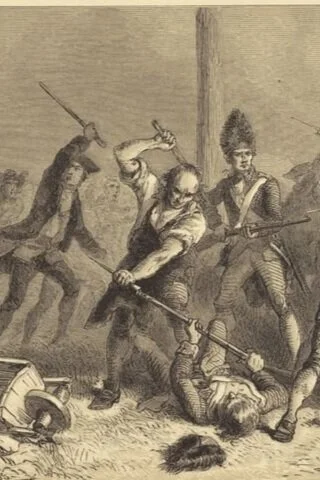

Wendy Bellion and Shira Lurie

For the last installment in our six-part series on monuments in / about colonial Gotham, Wendy Bellion and Shira Lurie discuss NYC’s rebellion against British rule during the volatile decade before the War for Independence. Bellion begins with a story of destruction — the tearing down of the statue of George III in Bowling Green. Lurie tells of construction — the raising of five liberty poles on the Common (present day City Hall Park).

Read MoreMapping the Suffrage Metropolis

By Lauren C. Santangelo

Last summer, Oxford University Press published my book, Suffrage and the City: New York Women Battle for the Ballot. The book examines how leaders in such suffrage organizations as the New York City Woman Suffrage League and the Woman Suffrage Party perceived New York City, how those perceptions changed over the course of five decades, and how they informed campaign strategies.

Read MoreThe Toughest Gun Control Law in the Nation: The Unfulfilled Promise of New York’s SAFE Act

Reviewed by Andrew C. McKevitt

When Governor Andrew Cuomo pushed a new gun control law, the Secure Ammunition and Firearms Enforcement (SAFE) Act, through the New York State Assembly in January 2013, just a month after the tragic mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, critics said he acted in haste. Cuomo’s administration started drafting a bill before the New Year; it submitted the bill to the Assembly on January 13 and, utilizing a rare emergency measure, the governor signed it an incredible 18 hours later.

Read MoreSwept From the Streets: Mario Procaccino and the Rise of Law-and-Order Politics in New York City

By Gabe S. Tennen

Mario Angelo Procaccino strode down Fulton Street, waving to onlookers and shaking hands. Accompanied by his running mate for city council president, Abraham Beame; his teenage daughter, Marierose; and a cabal of campaign staff, the Democratic candidate for mayor seemed at home in the working-class shopping center in Downtown Brooklyn.[1] In 1969, the appearance of Procaccino, then serving as city comptroller, at a blue-collar hub outside of Manhattan was both practical and symbolic. Attempting to assemble a coalition of voters dissatisfied with the liberal bent of incumbent Mayor John V. Lindsay, Procaccino considered outreach to white homeowners in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island his best chance to ascend to City Hall. Beginning his excursion in front of Mays Department Store, a campaign spokesman with a bullhorn declared to passers-by that “John Lindsay probably doesn’t even know where Mays Department Store is!”[2] As he had done throughout his Democratic primary campaign, the pencil-mustached, diminutive Procaccino would allude to that gulf between a Manhattan-reared, Protestant, Yale-educated mayor and a working-class Catholic and Jewish outer-borough constituency during the general election. The issue that most galvanized that effort was one gaining traction across the country: “law-and-order.”

Read MoreBattling Bella: The Protest Politics of Bella Abzug

Reviewed by Dylan Gottlieb

“She is loud. She is good and rude,” wrote Jimmy Breslin, the redoubtable New York newspaperman. Like “a fighter in training,” he continued, Bella Abzug was “pushing, brawling, poking, striding her way toward the Congress of the United States.” In the 1970s, as New York approached its nadir, Abzug emerged onto the political scene as a pugilist for the people: a “tough broad from the Bronx” (to borrow the title of another biography), whose combative style and populist message fit the tough times.

Read More