Mastering Paradox: John Jay as a Slaveholding Abolitionist

By David N. Gellman

“Alexander Hamilton, Enslaver? New Research Says Yes” announced the New York Times in a November 2020 news story. A paper published online by Jessie Serfilippi, a researcher at the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site, uncovered striking new evidence to clarify long muddied waters about Hamilton’s personal connections to this deep-seated New York institution. Serfilippi’s dogged research is proof once again that even traditional archives still hold revelations.

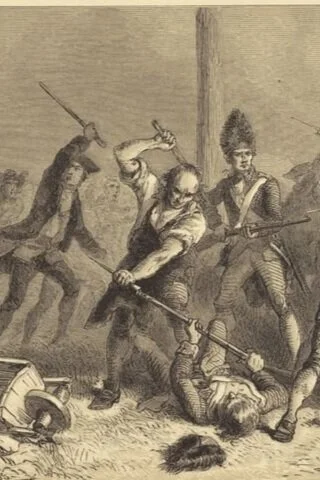

Read More“God is Forgotten, and the Soldier Slighted”: New York City’s Golden Hill and Nassau Street Riots and the Affective Rhetorics of Crowd Violence

By Russell L. Weber

Winter’s chill clutched New York City the morning of January 19, 1770. Such unwelcoming weather might have persuaded some New Yorkers to remain indoors, supply their stoves with more kindling, and delay their trip to the market until warmth returned to either their bones or their city. The soldiers of Britain’s 16th Regiment of Foot, however, ignored January’s harsh bite. As these regulars made the half-mile walk from their barracks to Fly Market, their enraged, boiling blood kept them warm.

Read MoreIn Service to the New Nation: An Interview with Robb K. Haberman of The John Jay Papers Project

Interviewed by Helena Yoo Roth

Few political leaders in the revolutionary and early nationals eras were more influential than John Jay (1745-1829). A New Yorker born and bred and a 1765 graduate of the nascent King’s College, this austere lawyer of Huguenot and Dutch descent went on to lead a life marked by continuous service and a steadfast devotion to his family, state, and country. The John Jay Papers Project based at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Columbia University has documented Jay’s life through a series of published volumes containing his personal correspondence and public papers.

Read MoreMyles Cooper and “the Din of War”

By Christopher F. Minty

Rev. Charles Inglis was distraught. “I cannot express the Distress I felt at hearing of your Embarkation for England, & the Cause of it,” he wrote. It was June 1775 and Myles Cooper, his close friend and colleague, had recently departed Manhattan for Britain. Cooper, one of the city’s most prominent and outspoken loyalists, and had long been targeted by revolutionaries. Just a few months before, he was among five New Yorkers who were warned in a April 25, 1775 letter from “Three Millions” that Parliament’s “Repeated insults and unparalleled oppressions” had reduced colonial Americans “to a state of desperation.”

Read MoreMonuments of Colonial New York: George III and Liberty Poles

Wendy Bellion and Shira Lurie

For the last installment in our six-part series on monuments in / about colonial Gotham, Wendy Bellion and Shira Lurie discuss NYC’s rebellion against British rule during the volatile decade before the War for Independence. Bellion begins with a story of destruction — the tearing down of the statue of George III in Bowling Green. Lurie tells of construction — the raising of five liberty poles on the Common (present day City Hall Park).

Read MoreA Loyalist and His Newspaper in Revolutionary New York

By Joseph M. Adelman

New York in the 1760s was a divided town, riven by local factions as well as imperial politics. Local elections were fiercely contested, as they had been for decades. The imperial crisis didn’t help.

Read MoreRevolutionary Networks: The Business and Politics of Printing the News, 1763-1789

Reviewed by Jonathan W. Wilson

Have pity for John Holt. He lived in perilous times. As the publisher of the New-York Journal, and as a centrally located postmaster, Holt was poised to play an important role in the American Revolution. His evident sympathies were with the patriots. But he had to be careful.

Read MoreThe Carleton Commission and Evidence of Arson in the Great New York Fire of 1776

By Bruce Twickler

In October of 1783, just six weeks before the British evacuated New York, the Commander-in Chief-of the British forces, Sir Guy Carleton, commissioned a panel of three British officers to investigate the disastrous fire that devastated the city seven years earlier. Shortly after midnight on September 21, 1776, fire had erupted in lower Manhattan. By daybreak it had consumed five hundred buildings – including schools, churches, warehouses and homes – and caused more destruction than all the previous colonial fires in New York combined.

Read MoreIconoclasm in New York: Revolution to Reenactment

Reviewed by Benjamin L. Carp

New York is a city of destruction. What doesn’t burn by accident, somebody tears down on purpose. When Chip asks Hildy to take him to the Hippodrome in Leonard Bernstein’s On the Town, she replies, “It ain’t there anymore,” which might as well be the city’s motto. Nothing is too sacred to shatter. Nothing is too exalted to escape the city’s brutal contests over money and power.

Read More