Nieuw Amsterdam As Manhattan

By Harrison Diskin

In the summer of 1641, a Wiechquaskeck man murdered Claes Smits, an aged wheelwright who lived in a small house north of Fort Amsterdam. He had visited Smits’ house to exchange beaver skins for duffels of cloth. But as Smits bent over to grab the cloth from a chest, the Native man (the records have not preserved his name) struck him dead with an axe. The Commander of the Dutch garrison at Fort Amsterdam pursued the man back to his village and accosted him with questions.

Read MoreProjecting “Spread City”: The New York Metropolitan Region Study and Its Critics, 1956–1968

By Peter Ekman

“This project is not a blueprint for action. It has no recommendations to make about the physical structure of the Region or about the form or activities of the governmental bodies there. At the same time, it is a necessary prelude to future planning studies of the Region.” The project in question was the New York Metropolitan Region Study (NYMRS), executed 1956–59 for the Regional Plan Association (RPA) by an interdisciplinary group of scholars from Harvard’s Graduate School of Public Administration. Unlike the RPA’s original Regional Plan of New York, issued 1929–31, which was zealously promoted to the public and substantially implemented by 1940, the ten-volume NYMRS very deliberately was not a plan.

Read MoreThe Jewel of Eastern Long Island:

Precarity and the Peconic Bay Scallop Industry

By Erin Becker

Peconic Bay scallops, argopecten irradians, are the jewel of the Eastern Long Island recreational and commercial fishery; their market rate can be as high as $30 for a single pound. The shellfish are a fall and winter delicacy throughout the Northeastern United States. Peconic Bay scallops have enormous cultural and economic significance.

Read MoreDesign for the Crowd: Patriotism and Protest in Union Square

Reviewed by Donald Mitchell

Almost immediately after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, crowds started gathering in Union Square, the closest big public space to Lower Manhattan’s “exclusion zone.” People brought candles and photographs, flowers and flags. They came to mourn and to commune, turning the square into “a shrine and memorial, layered with photos, handwritten messages, schoolchildren’s drawing, expressions of sympathy and sorrow from flight attendants who had been spared the luck of the draw,” as Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin later wrote.[1] Quiet and dedicated mostly to mourning in the first days, Union Square soon also became a place of debate and discussion: what should America’s response be to the attacks? Why invade Afghanistan? How to understand America’s geopolitical role in the world?

Read MoreGreat Grandma Barrett was a Shining Woman: Reflections on the Radium Girls and Industrial Disease

By Erin Elizabeth Becker

“The great wonders of the world are sometimes listed as the telephone, wireless telegraphy, radium, spectrum analysis, the airplane, anesthetics, and antitoxins and X rays”

- The Long Island Traveler, November 13, 1925

On February 27, 1905, Marion Murdoch O’Hara was born in New York City, the daughter of two immigrants. Her father, George P. O’Hara, had immigrated to the United States from Liverpool and found work in New York City as a janitor. Her mother, Marion Dunlop, was a housewife from Scotland. Growing up in New York City, the younger Marion lived with her parents and two sisters. At age seventeen, she married Aiden J. Barrett, a twenty-three-year-old immigrant from Newfoundland in Rutherford, New Jersey. “Great Grandma Barrett was a dancer in New York City,” family stories go, “and- before he met her- Great Grandpa Barrett was studying to be a Catholic priest!” The couple would go on to have nine children together- Rosemary, Marion, Florence, George, William, John, Patricia, Robert, and Alice. They lived in Mt Vernon, New York for a time, but by 1925, they had settled in the Bronx.

Read MoreDutch Baymen, Blue Points, and Oyster Crazed New Yorkers

By Erin Becker

Beginning as early as 8,000 years ago, the land which would eventually become New York City was intrinsically connected to the oyster. The Lenape targeted shellfish as a food resource and left behind heaping shell middens. Upon arrival to the New World, the Dutch and English colonists found a familiar food source — the oysters of New York Harbor. For a time, it seemed oysters were an inexhaustible resource. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, oysters fed the rich and poor of New York City. Like the ubiquitous hot dog carts of today, oyster carts and cellars lined the streets of New York City, peddling affordable food to the masses.

Read MoreDo We Want to Exhibit a Clean or Unclean City? Private Contractors, Scavengers, and Waste Disposal at the 1939 New York World’s Fair

By Tina Peabody

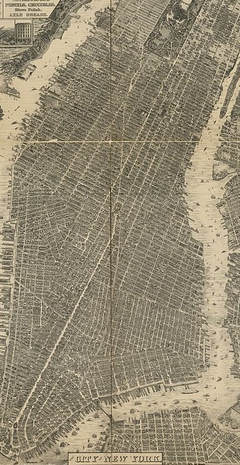

Read MoreMyth #6: The Grid Plan Caused Too Much Density and Rampant Land Speculation

By Jason M. Barr with Gerard Koeppel

In the two centuries since its creation, the grid plan has had no shortage of critics. Many, for example, have bemoaned its relentless monotony, its disregard for Manhattan’s topography and its lack of grand boulevards. In many respects, the grid has become a kind of Rorschach blot for the failures of 19th century New York to provide a cleaner, more efficient, and greener city. Detractors often see the plan as the cause or catalyst of the larger problems that New York confronted from rapid economic growth, massive immigration and poverty, and a municipal government that was, more or less, unable and unwilling to effectively handle these issues.

Read More